You’ve probably seen the "FDIC Insured" sticker on the glass door of your local bank a thousand times. It’s basically background noise at this point. But in the early 1930s, people would have literally fought—and they did—for that kind of peace of mind. To understand why we have the Banking Act of 1933, you have to picture a world where you wake up, walk to the corner, and find the doors to your life savings are bolted shut. No app. No customer service line. Just a "Closed" sign and the crushing realization that your money is gone forever.

Between 1929 and 1933, roughly 9,000 banks failed. It was a total collapse of trust.

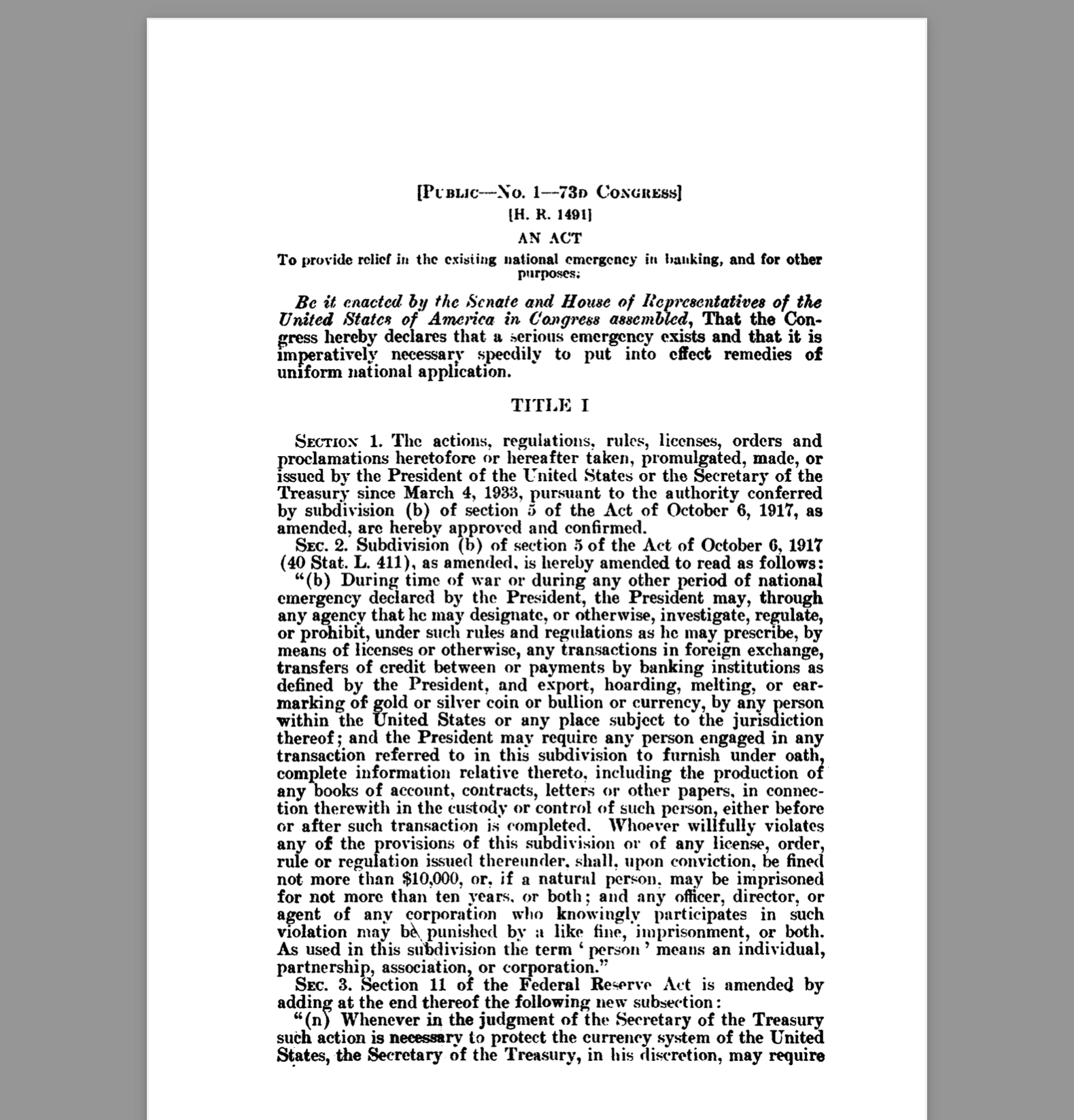

When Franklin D. Roosevelt took office, the financial system wasn't just leaking; it was underwater. The Banking Act of 1933, famously known as the Glass-Steagall Act, was the desperate, brilliant, and deeply controversial "hail mary" pass designed to stop the bleeding. It wasn't just a boring piece of paper. It was a radical divorce. It told banks they had to choose: you can either be a safe place for people to keep their paychecks, or you can be a high-stakes gambler on Wall Street. You can't be both.

The Mess Before the Magic

Why did we even need this? Honestly, it’s because banks in the 1920s were doing some pretty wild stuff with your grandma’s grocery money.

Commercial banks—the ones that took deposits—were using that cash to speculate on the stock market. They were underwriting risky securities and then turning around and selling those same shaky investments to their own depositors. It was a massive conflict of interest. When the market crashed in '29, the banks didn't just lose their own money; they lost everyone’s.

Senator Carter Glass, a former Treasury Secretary, and Representative Henry Steagall, the chairman of the House Banking and Currency Committee, weren't exactly best friends. They had very different ideas about how to fix the mess. Steagall was obsessed with protecting the small, rural banks. Glass wanted to rein in the big city players. Their compromise became the Banking Act of 1933, and it changed the American wallet for the next 66 years.

The Big Divorce: Glass-Steagall’s Wall

The most famous part of the Banking Act of 1933 was the separation of commercial and investment banking. It created a literal wall.

If you were a bank, you had to pick a side. Section 16 and Section 21 of the act were the "thou shalt not" rules. Commercial banks were barred from dealing in non-governmental securities. They couldn't underwrite stocks. They couldn't trade them for profit. On the flip side, investment firms couldn't take deposits.

🔗 Read more: Is Today a Holiday for the Stock Market? What You Need to Know Before the Opening Bell

This was huge. It meant that if Goldman Sachs wanted to go play in the stock market, they couldn't use your checking account balance as their chips. This separation lasted until 1999, when the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act tore the wall down, but we’ll get to that later. The point is, for decades, this rule made banking... well, boring. And boring is exactly what you want when it comes to your rent money.

Enter the FDIC: The Real Hero of the Banking Act of 1933

If Glass-Steagall was the wall, the FDIC was the safety net.

A lot of people don't realize that FDR actually hated the idea of deposit insurance at first. He thought it would encourage banks to be reckless because they knew the government would bail out the depositors. He called it a "guarantee of bad banking." But Steagall pushed for it because he knew people wouldn't put their money back into banks unless they knew it was 100% safe.

The Banking Act of 1933 created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Initially, it only insured up to $2,500. Today, that number is $250,000.

Think about the psychological shift that caused. Before 1933, if you heard a rumor that your bank was struggling, you ran there as fast as you could to get your cash out. That’s a bank run. After the FDIC was established, the incentive to run vanished. If the bank fails, the government sends you a check. Simple. It effectively ended systemic bank runs in America for a generation.

Regulation Q and the End of "Interest Wars"

Another weirdly important part of the Banking Act of 1933 was something called Regulation Q.

Back then, the government thought that if banks competed too hard for customers by offering high interest rates on checking accounts, they would be forced to make riskier loans to pay for those high rates. So, the Act just... banned interest on demand deposits. It also gave the Federal Reserve the power to set ceilings on interest rates for savings accounts.

💡 You might also like: Olin Corporation Stock Price: What Most People Get Wrong

It sounds anti-consumer today, right? But the logic was all about stability. They wanted to take the "hustle" out of banking. They wanted bankers to be the guys in the gray suits who went home at 3:00 PM, not aggressive sales reps trying to beat the guy across the street.

Why Everyone Is Still Arguing About It

If you follow financial news, you’ve heard people yelling about Glass-Steagall. When the 2008 financial crisis hit, a lot of experts—including people like Elizabeth Warren and even some old-school Republicans—pointed the finger at the 1999 repeal of the Banking Act of 1933’s core provisions.

The argument goes like this: once the wall was gone, banks got "Too Big to Fail." They started mixing risky investment banking (like mortgage-backed securities) with traditional commercial banking. When the "casino" side lost, it threatened the "safe" side, and the government had to step in with trillions in bailouts.

However, it’s not that simple.

Critics of the Act say it was an outdated relic. They argue that the 2008 crisis wasn't actually caused by the merger of commercial and investment banks. They point out that Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers—the firms that actually collapsed first—were pure investment banks. They weren't "mixed" banks. So, the Banking Act of 1933 wouldn't have saved them anyway.

Still, the spirit of the Act lives on in things like the Volcker Rule (part of the Dodd-Frank Act), which tries to limit banks from making certain types of speculative bets with their own money. It’s the same old fight: how much freedom should we give the people who hold our money?

Surprising Bits You Might Have Missed

The Banking Act of 1933 did a few other things that don't get the headlines.

📖 Related: Funny Team Work Images: Why Your Office Slack Channel Is Obsessed With Them

- It changed how the Federal Reserve worked. It gave more power to the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), which is the group that basically decides the interest rates you pay on your credit cards and car loans today.

- it required more disclosure. Banks couldn't just hide their "garbage" assets in affiliates.

- It tried to stop the "double liability" for bank shareholders, which was a terrifying old rule where if a bank failed, the shareholders had to pay out of their own pockets to cover the losses.

Basically, it was a massive "clean up the room" moment for the entire U.S. financial system.

Actionable Takeaways: What This Means for You Today

We aren't in 1933 anymore, but the lessons are incredibly relevant, especially with the recent collapses of places like Silicon Valley Bank or Signature Bank. Here is how you can use the legacy of the Banking Act of 1933 to protect yourself:

Know your limits. The FDIC is the crown jewel of this Act. Always, always make sure your bank is FDIC-insured. If you have more than $250,000 (congrats, by the way), don't keep it all in one bank. Spread it out. The $250,000 limit is per depositor, per insured bank, for each account ownership category.

Understand the "Shadow Banking" world. The Banking Act of 1933 only regulated traditional banks. Today, a lot of "banking" happens in places that aren't banks—like fintech apps, crypto exchanges, or money market funds. Many of these do not have FDIC insurance. If you’re putting money into a "neobank" or a high-yield app, read the fine print. Is your money actually sitting in a partner bank that is FDIC-insured, or is it just floating in the ether?

Watch the "Wall" movements. When you see news about "deregulation," they are usually talking about the remnants of the Banking Act of 1933. While the wall is technically gone, some guards remain. If those guards (like the Volcker Rule) get removed, it’s a signal that the system is getting "hotter" and riskier. That might be good for your stock portfolio in the short term, but it’s a red flag for your long-term cash stability.

Don't ignore the Fed. Since the 1933 Act centralized so much power in the Federal Reserve, their meetings are the most important dates on the economic calendar. When the FOMC speaks, the ghost of the 1933 Act is in the room. Their decisions on interest rates affect your ability to buy a house or grow a business far more than any individual bank's policy.

The Banking Act of 1933 wasn't perfect, and it certainly wasn't the "end" of financial history. But it was the moment we decided as a country that the person saving for a rainy day shouldn't have their umbrella gambled away by someone in a penthouse. Every time you see that FDIC logo, you’re looking at a piece of 1933 that is still working for you. Keep your eyes on your bank's stability, verify your insurance coverage, and remember that "boring" is usually a compliment in the world of finance.