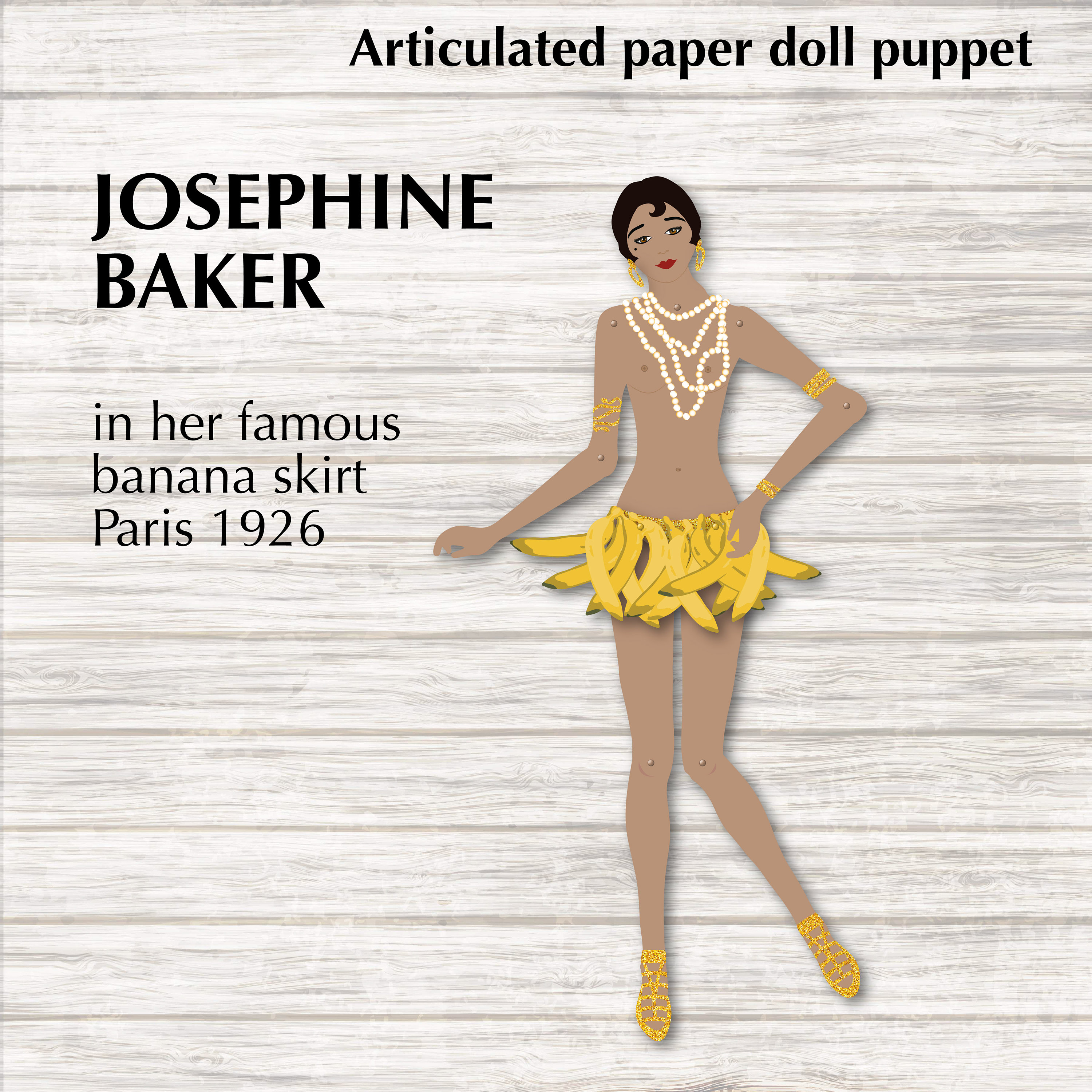

Paris, 1926. The air in the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées was thick with anticipation and the scent of expensive perfume. Then, she appeared. Josephine Baker didn't just walk onto the stage; she exploded onto it. She was wearing almost nothing. Just a string of artificial bananas around her waist. This moment, the infamous banana dance Josephine Baker performed in the "La Folie du Jour" revue, changed the trajectory of performance art forever. It was shocking. It was brilliant. It was, for many in the audience, their first encounter with a kind of raw, unapologetic Black femininity that the rigid social structures of Europe weren't prepared for.

Honestly, it’s hard to overstate how much this single costume choice redefined her career. People often think of it as just a scandalous outfit. It was so much more. Baker was a genius of self-invention. She knew exactly what she was doing. By leaning into the "primitive" tropes that white Parisians were obsessed with at the time—a movement known as Primitivisme—she took control of the gaze. She wasn't just a victim of a stereotype. She was the one driving the bus.

Why the Bananas Weren't Just a Joke

When we talk about the banana dance Josephine Baker made famous, we have to talk about the "Danse Sauvage." This wasn't some choreographed ballet. It was frantic. It was funny. It was deeply erotic. Baker would cross her eyes, stick out her tongue, and move her body in ways that seemed to defy the laws of physics. The bananas themselves—sixteen of them, originally made of rubber—jiggled and bounced as she performed her signature Charleston steps.

You’ve gotta understand the context of the Jazz Age. Paris was obsessed with "le tumulte noir." African and African-American culture were being consumed as exotic commodities. Baker, a girl from St. Louis who had fled the brutal racism of the United States, found a strange kind of freedom in this French obsession. She once said that the Eiffel Tower looked like her, "all skinny and tall." She was leaning into the joke. But the joke had teeth.

💡 You might also like: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

The Costume’s Evolution

The original costume was designed by Paul Colin. He was the artist who created the iconic posters we still see in cafes today. He didn't just want a skirt; he wanted a statement. Over the years, the costume changed. In later iterations, the bananas were encrusted with jewels. They became more "couture." This mirrored Baker’s own rise from a "savage" curiosity to the "Black Venus" and eventually to a high-society icon who wore Dior and befriended Princess Grace of Monaco.

The Subversive Power of the Dance

Critics at the time were split. Some saw it as high art. Others saw it as a circus act. But Baker was savvy. She was basically the first global Black female superstar. By playing the "primitive" role, she earned enough money and clout to eventually drop the act. She used her platform to fight for civil rights later in life, but it all started with those rubber bananas.

Think about the physical demand of that performance. To do the Charleston with that kind of intensity, while maintaining a comedic persona, requires elite athleticism. It wasn't just standing there looking pretty. It was a workout. It was a riot. It was a middle finger to everyone who thought a Black woman from the slums of Missouri couldn't conquer the world.

📖 Related: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

What Modern Audiences Get Wrong

A lot of people today look at the banana dance Josephine Baker did and feel uncomfortable. That's fair. It uses imagery that is undeniably rooted in colonialist racism. However, looking at it only through a modern lens misses the nuance of Baker's agency. She wasn't a passive participant. She was a collaborator in her own image-making. She leaned into the stereotype to explode it from the inside.

- She was the highest-paid entertainer in Europe.

- She owned a pet cheetah named Chiquita who wore a diamond collar.

- She used her tours to gather intelligence for the French Resistance during WWII.

She lived a life that was infinitely more complex than a skirt made of fruit. The dance was her entry point. It was the "hook" that got her into the room, and once she was in the room, she made sure no one would ever forget her name.

The Legacy in Pop Culture

You can see the DNA of the banana dance everywhere today. When Beyoncé performed at Coachella, or when Janelle Monáe evokes surrealist imagery in her videos, they are walking the path Josephine cleared. Baker taught the world that a performer could be both a sex symbol and a clown. She proved that you could be "othered" by society and still demand its absolute adoration.

👉 See also: The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads: Why This Live Album Still Beats the Studio Records

Actually, the dance became so iconic that it almost swallowed her whole. In her later years, she struggled to be seen as a serious activist and mother to her "Rainbow Tribe" of twelve adopted children. People always wanted the bananas. They wanted the 1926 version of her. But Josephine kept moving. She was always more interested in the future than the past.

How to Appreciate Baker’s Work Today

If you really want to understand the impact of the banana dance Josephine Baker gave the world, don't just look at still photos. Go find the grainy film clips. Watch the way her knees knock together. Notice the speed of her feet. Look at her eyes. She is constantly breaking the fourth wall. She is telling the audience, "I know you think this is what I am, but look at what I can do."

It’s about the shift from object to subject. In the beginning, she was an object to be looked at. By the end of the set, she was the subject in total control of the room. That is the true power of the performance.

Actionable Insights for History and Art Lovers

To truly grasp the weight of this moment in cultural history, consider these steps:

- Watch the Archival Footage: Search for "Josephine Baker 1927 film" to see the "Danse Sauvage" in motion. The static images don't capture the comedic timing that made her a star.

- Read "Josephine: The Hungry Heart": This biography by her son, Jean-Claude Baker, offers a raw, non-sanitized look at her life and the reality behind the "Black Venus" persona.

- Visit the Musée de l'Homme: If you're ever in Paris, they often have exhibits relating to the colonial era and the "Negrophilia" movement that fueled Baker's early success.

- Analyze the Parody: Look at how Baker used humor. She often crossed her eyes during the most "erotic" parts of her dance. This was a deliberate technique to subvert the male gaze and maintain her own humanity.

- Study Her Resistance Work: Balance the "banana dance" imagery with her work as a spy for the Free French Forces. She hid secret messages in her sheet music using invisible ink. Understanding her bravery makes her stage persona even more fascinating as a mask.

Baker’s story is a reminder that we are all allowed to reinvent ourselves. She took the world’s most reductive stereotypes and turned them into a gilded cage of her own design—then she walked out of the cage and became a hero. The bananas were just the beginning.