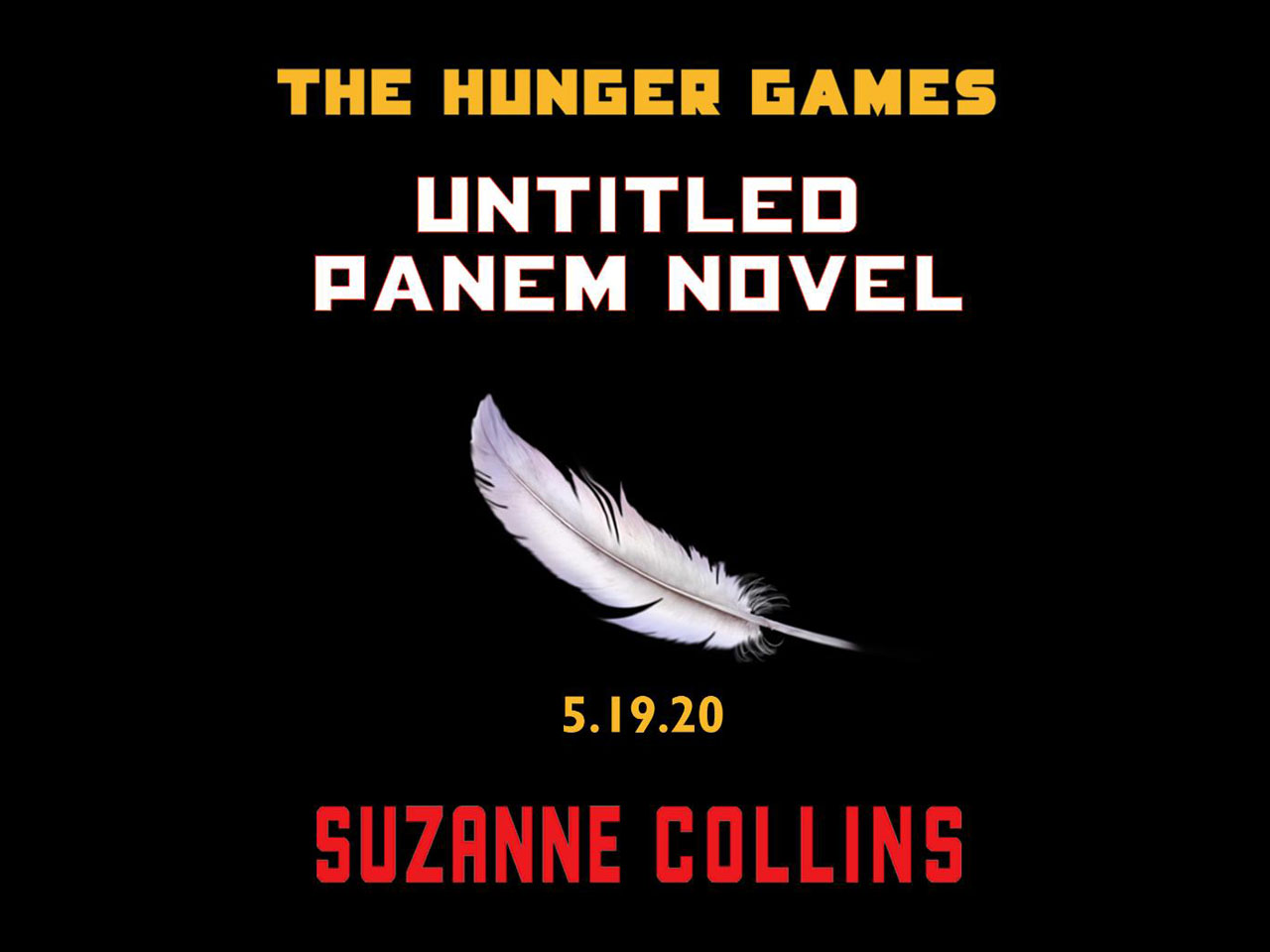

Suzanne Collins didn’t really have to write this book. After the massive, culture-shifting success of the original trilogy, most authors would have just retired to a quiet life or maybe written a fluffy sequel about Katniss and Peeta’s kids picking flowers in District 12. Instead, she gave us The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, a prequel that takes place sixty-four years before the first book. It's a weird, dense, and honestly kind of uncomfortable look at a young Coriolanus Snow. You know, the guy who eventually becomes the tyrannical President Snow who tries to murder everyone we love.

It’s a bold move.

Making a villain the protagonist is a high-wire act. If you make them too likable, you’re apologizing for a monster. If you make them too loathsome, nobody wants to read five hundred pages about them. Most fans were skeptical when the book was first announced in 2019. We wanted to know about Mags or maybe a young Haymitch Abernathy. We didn't necessarily want to spend time inside the head of a teenage sociopath. But Collins pulled it off by leaning into the grit of the "Dark Days."

What Most People Get Wrong About the 10th Hunger Games

The Panem we see in The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes isn't the shiny, high-tech Capitol we know from the Katniss era. It’s a wreck. The war with the Districts ended only a decade prior, and the city is still covered in rubble. People are hungry. Even the "elite" Snow family is essentially broke, hiding their poverty behind threadbare velvet curtains and eating nothing but cabbage. This is the first thing readers usually miss: the prequel is a post-war reconstruction story.

The Games themselves are also a disaster. They aren't a televised spectacle yet. There are no stylists, no high-tech arenas, and no "Girl on Fire." The tributes are thrown into a dilapidated sports circus, left to starve in filth, and die in ways that feel much more like a grubby execution than a sporting event. Coriolanus is part of the first group of Academy students assigned to "mentor" these kids, but it’s mostly a PR stunt to get people to actually watch the Games, because—get this—back then, nobody in the Capitol even liked watching them. They found it distasteful.

Snow’s job is to turn Lucy Gray Baird, the tribute from District 12, into something people care about. Lucy Gray is the polar opposite of Katniss Everdeen. While Katniss was a reluctant soldier who hated the spotlight, Lucy Gray is a performer. She’s part of the Covey, a group of nomadic musicians who got stuck in District 12 when the borders closed. She wears a rainbow dress and carries a guitar. She understands that in a world of cruelty, charm is a weapon.

✨ Don't miss: Why La Mera Mera Radio is Actually Dominating Local Airwaves Right Now

The Philosophy of the Arena

Collins uses this book to argue with herself. Or rather, to argue about the nature of humanity. Throughout the narrative, Snow is mentored by Dr. Volumnia Gaul, the Head Gamemaker and a genuinely terrifying woman who keeps mutated snakes in her lab. Gaul is a Hobbesian. She believes that humans are inherently violent and chaotic, and that without the firm, crushing hand of the state, we would all tear each other's throats out.

The Hunger Games, in her view, are a "contract." They are a reminder of what happens when the social order breaks down.

Snow is caught between Gaul’s nihilism and the influence of his friend Sejanus Plinth. Sejanus is a "District kid" whose father bought his way into Capitol citizenship. He hates the Games. He thinks they are a moral abomination. Watching Snow navigate these two extremes is like watching a car crash in slow motion. You want him to choose Sejanus. You want him to find his humanity through Lucy Gray. But the book is a tragedy because we already know how it ends. We know the man he becomes.

Why Lucy Gray Baird Is the Anti-Katniss

A lot of the discourse around The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes focuses on the "romance" between Snow and Lucy Gray. Is it real? Honestly, probably not in the way we want it to be. For Snow, Lucy Gray is a prize. She is something he "owns" or "protects" to ensure his own future. He is obsessed with her, sure, but his love is possessive. It’s transactional.

Lucy Gray is far more clever than people give her credit for. She uses Snow just as much as he uses her. She needs him to survive the arena, and she’s smart enough to play the part of the tragic lover to get the food and water she needs to stay alive. When they eventually flee to the woods outside District 12 in the final act, the tension is unbearable. You realize that neither of them truly trusts the other.

🔗 Read more: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

The ending of the book is famously ambiguous. Did Snow try to kill her? Did she escape? Collins leaves it open, which is brilliant because it mirrors the "ghost" status Lucy Gray holds in Panem’s history. By the time Katniss comes around, Lucy Gray has been totally erased from the records. She’s just a legend or a song.

The Evolution of the Games

If you’re a lore nerd, this book is a goldmine. You get to see the literal invention of:

- Sponsorships: Snow realizes that if people can give gifts to tributes, they become "invested" in the outcome.

- Betting: Turning the Games into a gamble makes them addictive for the Capitol citizens.

- The Arena as a Character: Dr. Gaul starts experimenting with mutts (those creepy hybrid animals) during the 10th Games, realizing that the environment needs to be as dangerous as the kids.

- The "Victory" Tour: The idea that the winner should be a celebrity rather than just a survivor.

It’s a chilling look at how a bureaucracy learns to market atrocity. Snow doesn't just survive the Games; he perfects them. He realizes that if you make the horror entertaining, people will stop asking why it’s happening in the first place.

The Problem With Empathy

There’s a real risk in writing a book like this. Some readers felt that by showing Snow’s trauma—his hunger, his fear, his loss of his parents—Collins was trying to justify his later actions. I don't see it that way. If anything, the book is a warning. It shows that evil isn't always born; it’s built. It’s a series of small, selfish choices. Snow had chances to be better. He had friends who loved him and a girl who trusted him. He threw them all away for the sake of "order" and his own advancement.

The prose is different here than in the original trilogy. Since it’s third-person perspective rather than Katniss’s first-person "I," there’s a coldness to it. You aren't in Snow’s heart; you’re looking over his shoulder, and what you see is a boy who is terrifyingly good at rationalizing his own cruelty.

💡 You might also like: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

It’s also worth mentioning the 2023 film adaptation. Tom Blyth and Rachel Zegler did a fantastic job, but the book handles the internal monologue much better. In the movie, Snow’s descent feels a bit fast. In the novel, it’s a slow, agonizing crawl into the dark. You see every gear turn in his head as he decides to betray Sejanus. You feel the exact moment his heart hardens for good.

How to Approach the Prequel Today

If you’re planning on diving into The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, don't expect a fun YA adventure. It’s a political thriller disguised as a dystopian novel. It's much longer than the previous books and moves at a different pace. The first two acts are centered on the Games, while the third act is a strange, atmospheric "western" set in District 12.

Actionable Insights for Readers and Fans:

- Read it as a companion to the original trilogy, not a sequel. Look for the "echoes." When you hear the song "The Hanging Tree," remember that Snow is the one who first heard Lucy Gray sing it. It adds a layer of psychological horror to the original books—Snow wasn't just mad that Katniss was a rebel; she was singing a song that reminded him of the only woman he ever (sort of) loved and the man he killed.

- Pay attention to the names. Collins loves her Roman history. Coriolanus is named after a Roman general who held the common people in contempt. Crassus, Casca, Agrippa—these aren't just cool-sounding names; they are nods to the fall of the Roman Republic, which is exactly what Panem is modeled after.

- Watch for the "Mutt" metaphor. In the prequel, the line between human and animal is constantly blurred. Snow views the District people as animals that need to be caged. By the end of the book, you realize that the real "mutt" is the one who lost his humanity to keep the cage locked.

- Analyze the "Three Es." Dr. Gaul asks Snow what the Hunger Games are for. He eventually lands on the "Three Es": Enrollment, Enlightenment, and Punishment (well, the third one changes as his philosophy evolves). Try to identify which of these elements is present in every interaction Snow has with the tributes.

Ultimately, the prequel doesn't "fix" Snow or make him a hero. It just makes him more terrifying. It shows us that the monster in the high balcony didn't come from nowhere. He was a kid who was hungry, who was scared, and who decided that his own safety was worth more than the lives of everyone else in the world.

It’s a grim lesson, but in the world of Panem, it’s the only one that ever really mattered. Collins didn't give us the story we wanted, but she gave us the one that actually explains how the world broke. If you want to understand the modern political landscape or the way entertainment can be weaponized, you could do a lot worse than studying the rise of Coriolanus Snow. It's a uncomfortable mirror, but it's one worth looking into.

To get the most out of your re-read, compare the "Covey" philosophy of collective living to the Capitol’s hyper-individualism. You'll find that the true "rebellion" wasn't just about guns; it was about refusing to view other people as competition. Snow couldn't handle that, and that's why he had to destroy it. Stop looking for a hero in this story—the hero is the realization that you don't want to be like any of them.