Honestly, the moment you hear that opening line about Jesse James being a "lad who killed many a man," you're not just listening to a song. You're stepping into a crime scene that’s been frozen in amber since 1882. It’s wild. This isn't just a folk tune; it's a massive piece of PR that turned a cold-blooded guerrilla into a misunderstood American Robin Hood.

If you grew up with the version by Woody Guthrie, Bruce Springsteen, or even Pete Seeger, you’ve heard the story. Jesse was brave. Jesse was a friend to the poor. And then there was Robert Ford—that "dirty little coward"—who shot Jesse in the back while he was just trying to hang a picture on the wall.

It’s a great story.

But history is rarely that clean.

The Myth vs. The Man: What the Lyrics Get Wrong

The Ballad of Jesse James is basically the 19th-century version of a viral TikTok, except it was written by a guy named Billy Gashade (or maybe LaShade, nobody really knows) right after Jesse was killed. Gashade wanted to paint a picture. He claimed Jesse "stole from the rich and gave to the poor."

He didn't.

Jesse James was a Confederate bushwhacker who never actually shared his loot with anyone outside his gang or his family. The "giving to the poor" bit was a total fabrication designed to make him a hero to Missourians who were still salty about losing the Civil War. Historian T.J. Stiles, who wrote the definitive biography Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War, points out that Jesse actually targeted people based on their politics, not their bank accounts. He wasn't robbing "the rich"; he was robbing his enemies.

🔗 Read more: How Old Is Paul Heyman? The Real Story of Wrestling’s Greatest Mind

Then there's the "dirty little coward" himself, Robert Ford.

The song treats Ford like the ultimate traitor. It says he "ate of Jesse's bread and slept in Jesse's bed." While that's technically true—Ford was a member of the gang and was staying at Jesse's house under an alias—the song leaves out the part where Jesse was becoming increasingly paranoid and was likely going to kill Ford anyway. Ford was a nineteen-year-old kid who saw a chance to get a reward and get out alive.

It worked. Sorta.

He got the reward, but the ballad made sure he was hated for the rest of his life. He ended up running a tent saloon in Colorado before getting shot himself in 1892.

Why We Still Sing It

So why does this song still show up on every folk album since 1920? Because it taps into something deep. We love an underdog. We love the idea of someone sticking it to the "big guys"—the banks and the railroads that were squeezing farmers in the late 1800s.

The ballad survived because it’s catchy as hell.

💡 You might also like: Howie Mandel Cupcake Picture: What Really Happened With That Viral Post

The structure is simple:

- A verse about Jesse’s "brave" exploits (robbing the Glendale train, for example).

- The "coward" chorus that everyone knows by heart.

- A final verse about how the "news did arrive."

It’s designed for a sing-along. When Bentley Ball first recorded it in 1919, he set the template. Later, Woody Guthrie used the same melody for his song "Jesus Christ," essentially comparing the betrayal of Jesus to the betrayal of Jesse James. That's a bold move, but it shows how much of a "secular saint" Jesse had become in the eyes of the working class.

The Reality of the "Picture on the Wall"

One of the most famous lines in the Ballad of Jesse James describes his death: "While Jesse hung a picture on the wall."

This is actually one of the few factually accurate parts of the song. On April 3, 1882, in St. Joseph, Missouri, Jesse James (living as Thomas Howard) noticed a dusty picture of a horse. It was a hot day. He had taken off his coat and his pistols so he wouldn't look suspicious to neighbors.

He stepped on a chair.

He turned his back.

📖 Related: Austin & Ally Maddie Ziegler Episode: What Really Happened in Homework & Hidden Talents

Bob Ford fired a .44 caliber Smith & Wesson into the back of his head.

The song claims the "people held their breath" when they heard the news. In reality, they flocked to the house. They wanted souvenirs. People were literally dipping their handkerchiefs in his blood. It was a circus.

Actionable Insights for Folk Fans and Historians

If you're looking to dive deeper into the real story or perhaps learn to play the song yourself, here are a few things you can actually do:

- Listen to the 1924 Bascom Lamar Lunsford recording: This is one of the rawest, most "authentic" sounding versions. It gives you a feel for how the song would have sounded in the Appalachian hills.

- Visit the Jesse James Home Museum: It's in St. Joseph, Missouri. You can literally see the hole in the wall where the bullet went through. It’s a bit macabre, but if you want the real history, that's the place.

- Read "Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War" by T.J. Stiles: If the ballad makes you curious about the politics behind the man, this book is the gold standard. It strips away the Robin Hood myth and replaces it with a fascinating, darker truth.

- Compare the Lyrics: Look at how the song changes between Woody Guthrie's version and Bruce Springsteen’s We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions. Notice what they keep and what they leave out. It tells you a lot about what each era needed from its outlaws.

The Ballad of Jesse James isn't a history book. It's a protest song. It’s a piece of folk art that proves that in America, a good story is usually worth more than the cold, hard truth.

Next time you hear that chorus kick in, remember: you're not just singing about a robber. You're singing about how we choose to remember our villains.

Next Steps for You

- Track Down the "Billy Gashade" Mystery: Look into the various theories about who wrote the song—some say it was a black convict, others say a local printer.

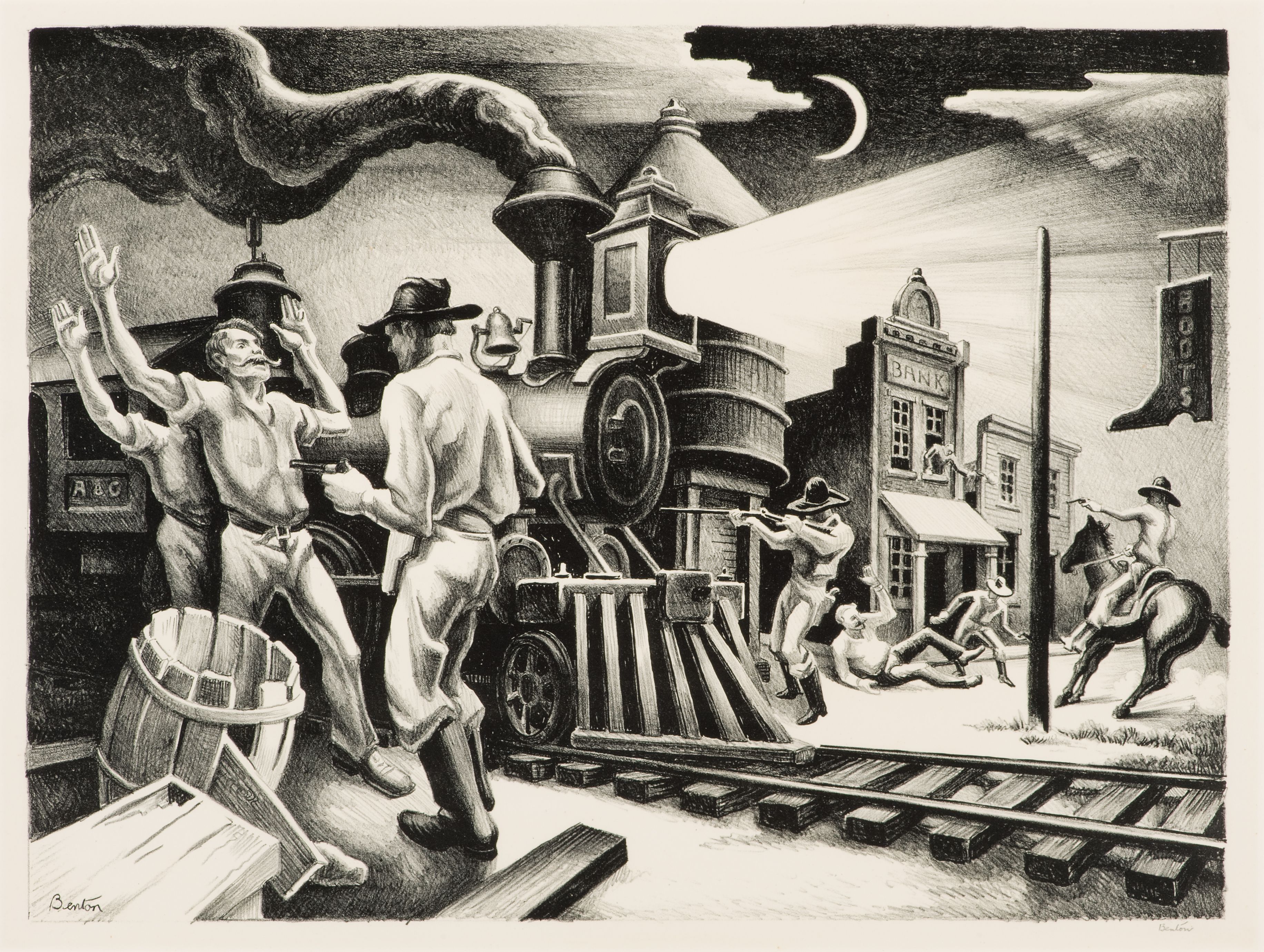

- Check Out the Thomas Hart Benton Mural: See the "Social History of Missouri" mural in the Missouri State Capitol, which features the ballad's lyrics and Jesse himself.

- Learn the G-C-D Progression: Most versions of the song use a simple 1-4-5 chord structure in the key of G. It’s a perfect "beginner" folk song for guitar or banjo.