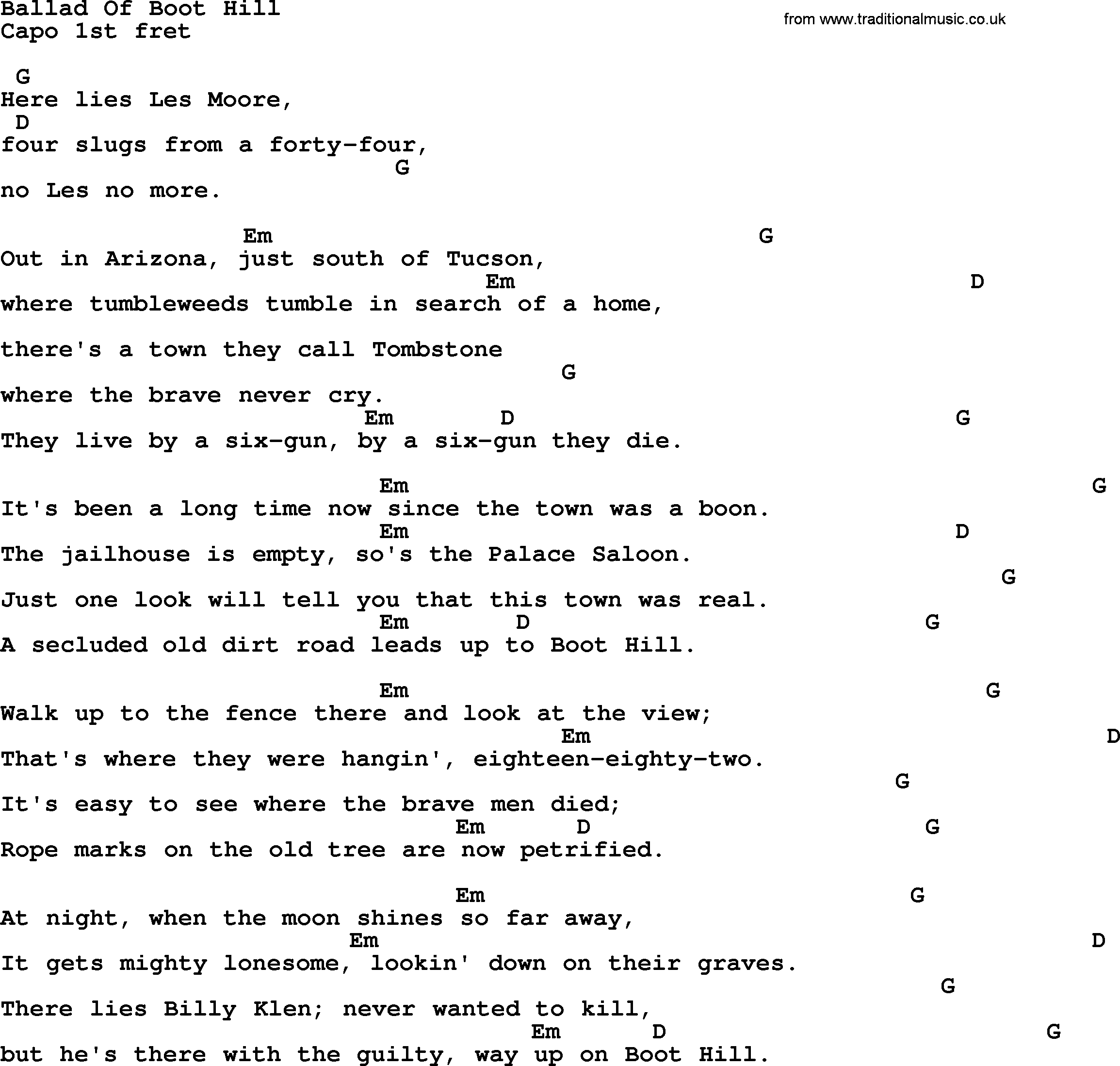

Johnny Cash didn’t just sing songs; he inhabited them. When you listen to The Ballad of Boot Hill, you aren't just hearing a track from 1959. You’re standing in the dust of Tombstone. You can practically smell the gunsmoke and the rot of the old gallows. Honestly, most people think this is just another "cowboy song" from his early Columbia years, but there’s a lot more weight to it than that.

The track first surfaced on an EP titled Johnny Cash Sings 'The Rebel – Johnny Yuma'. Later, it found a permanent home on the 1965 masterpiece Sings the Ballads of the True West. It’s a haunting piece of storytelling that captures the exact moment the Old West stopped being a frontier and started becoming a graveyard.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Songwriter

You’d think Johnny wrote this himself. It sounds like him. It feels like him. But he didn't.

Carl Perkins wrote the lyrics. Yeah, the "Blue Suede Shoes" guy.

It’s a wild pivot from rockabilly dance floors to the somber silence of an Arizona cemetery. Perkins had this uncanny ability to tap into the folk tradition of the American West. While Cash is the one who gave the song its gravelly soul, Perkins provided the poetic blueprint. They were close friends—brothers in arms at Sun Records—and you can hear that mutual respect in every note. Cash isn't just covering a song; he’s delivering a eulogy for a friend’s vision.

🔗 Read more: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

The Real People Buried in the Lyrics

The song isn't just vague Western imagery. It calls out specific names and places that you can actually visit today if you’re brave enough to drive into the Arizona heat.

- Lester Moore: The song kicks off with that famous, dark-humored epitaph: "Here lies Lester Moore, four slugs from a .44, no Les, no more." This isn't a writer's invention. Lester Moore was a real Wells Fargo agent who got into a shootout with a disgruntled customer over a package. They both died. The tombstone is still there in Tombstone’s Boot Hill.

- Billy Clanton: Cash mentions Billy, saying he "never wanted to kill." This refers to the youngest participant in the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. History is messy—some see the Clantons as outlaws, others as victims of the Earp brothers’ brand of "justice." Cash leans into the tragedy of the youth lost to the sixgun.

- The Year 1882: The lyrics mention the rope marks on the oak tree being petrified. In 1882, the law in Tombstone was often settled at the end of a hemp rope.

The Sound of the True West

Johnny Cash was obsessed with authenticity. When he recorded Sings the Ballads of the True West, he didn't want a polished Nashville sound. He wanted it to feel dry. Desolate.

He brought in the heavy hitters for these sessions. You’ve got Luther Perkins on that iconic "boom-chicka-boom" guitar and Marshall Grant holding down the bass. But look at the depth of the backing: Maybelle Carter on the autoharp and even the Statler Brothers on background vocals.

It’s a sparse arrangement.

💡 You might also like: Why Grand Funk’s Bad Time is Secretly the Best Pop Song of the 1970s

The silence between the notes is just as important as the music itself. It mimics the vast, empty spaces of the desert. When Cash sings about the "jailhouse being empty" and the "Palace Saloon" being quiet, the music feels just as hollowed out. It’s atmospheric storytelling at its peak.

Why The Ballad of Boot Hill Matters in 2026

We live in a world of digital noise. Everything is fast. Everything is loud.

The Ballad of Boot Hill is the opposite of that. It’s a reminder of consequence. The song isn't glorifying the gunfight; it's looking at the aftermath. It’s looking at the "lonely graves" under the moon.

Most Western songs of that era were about the "heroic" lawman. Cash and Perkins flipped the script. They focused on the losers. The ones who died for nothing. The ones who are just names on a rotting piece of wood now. That’s why it feels so human. It’s not a movie; it’s a tragedy.

📖 Related: Why La Mera Mera Radio is Actually Dominating Local Airwaves Right Now

A Legacy Beyond the Record

If you want to truly appreciate the song, you have to look at where it sits in the Cash catalog. It’s the bridge between his early Sun Records "rebel" persona and the "Man in Black" authority he would later command in the 1990s with Rick Rubin.

You can hear the seeds of the American Recordings in this 1959 track. The same grim fascination with death and redemption is right there, decades before "Hurt" or "The Man Comes Around."

How to Experience This Story Today

Don't just stream the song. To get the full weight of what Cash was doing, you should:

- Listen to the 1965 version on Sings the Ballads of the True West. It’s a concept album, and hearing it in the context of the other tracks makes the atmosphere much thicker.

- Look up the Tombstone epitaphs. Search for the actual photos of the graves of Lester Moore and the Clanton family. Seeing the weathered wood makes the lyrics hit harder.

- Check out the live version. Cash performed this with Carl Perkins at the London Palladium in 1968. Seeing the two creators together on stage gives the song a different, more collaborative energy.

The song is a masterclass in how to turn history into myth without losing the truth of the human experience. It’s dusty, it’s dark, and it’s quintessentially Johnny Cash.