You just bought a vintage Seiko watch. You’ve never really noticed them before, but suddenly, they’re everywhere. The guy at the coffee shop is wearing one. There's a listing for a gold-plated version on your social feed. Even your favorite character in a random 90s sitcom is rocking a "Pogue."

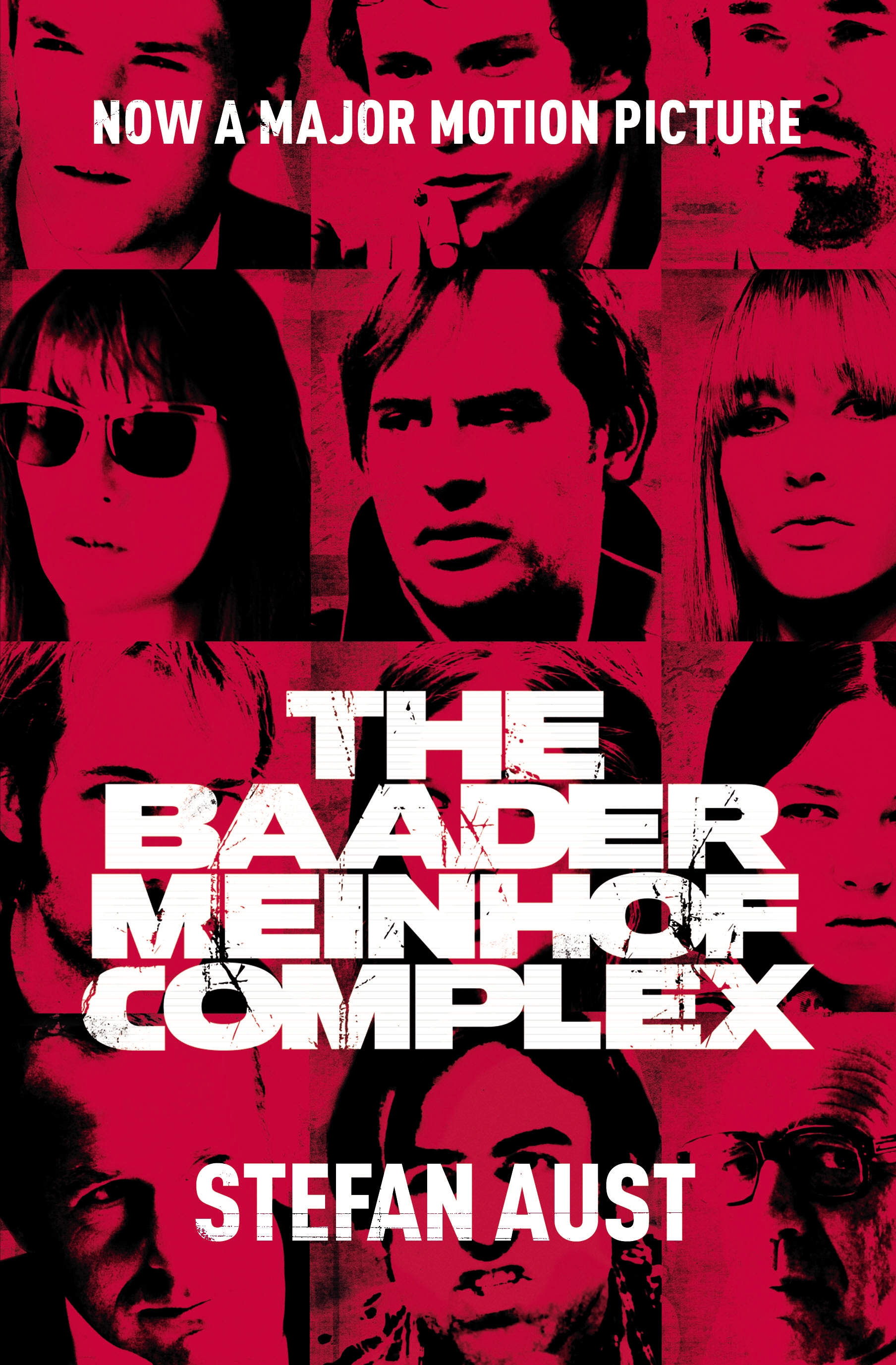

It feels like the universe is glitching. Is it a sign? A weird cosmic coincidence? Honestly, it’s just your brain being efficient. This phenomenon is called the Baader-Meinhof complex, though in clinical circles, you’ll hear it referred to as frequency illusion.

It’s that "once you see it, you can't unsee it" feeling. It happens with words, cars, niche historical facts, and even specific types of shoes. One minute, the information doesn't exist to you. The next, it’s the only thing you notice.

Where did the name Baader-Meinhof complex even come from?

The name is actually a bit of a historical accident. It has nothing to do with psychology researchers or lab studies. Instead, it traces back to a 1994 online discussion board on the St. Paul Pioneer Press website.

A reader wrote in about a specific experience: he had just heard of the West German far-left militant group, the Baader-Meinhof Group (also known as the Red Army Faction), and then suddenly encountered the name again shortly after.

After he shared this, other readers started chiming in with their own stories of hearing an obscure name and then seeing it everywhere within 24 hours. The name stuck. It’s a bit ironic because the actual Red Army Faction was a violent, controversial group, yet their name is now forever linked to a harmless cognitive quirk about noticing yellow Volkswagens or new slang.

Stanford linguistics professor Arnold Zwicky eventually gave it a more "official" name in 2005. He called it frequency illusion. He broke it down into two specific movements in the brain: selective attention and confirmation bias.

The gears turning inside your head

Your brain is basically a filter. If you processed every single stimulus—every bird chirp, every license plate, every scent of burnt toast—you’d have a total meltdown by noon. To keep you sane, your brain ignores almost everything.

Selective attention is the first half of the Baader-Meinhof complex. When you learn something new, like the definition of "obfuscate" or the existence of a specific breed of dog, your brain marks that info as "relevant."

Suddenly, the filter lets that specific thing through.

The second half is confirmation bias. This is the part that makes it feel spooky. Your brain thinks, "Wow, I've seen this three times today; it must be getting more popular!" You start looking for more instances to prove your theory that the thing is trending.

You aren't actually seeing it more. You’re just finally noticing it.

Think about the "New Car Effect." You buy a white Subaru Crosstrek. You thought it was a unique choice. Suddenly, you realize that every third car in the grocery store parking lot is a white Subaru Crosstrek. They were always there. You just didn't care about Crosstreks yesterday.

Why this matters for how we think

This isn't just a fun "did you know" fact for parties. The Baader-Meinhof complex has some real-world weight, especially in how we form opinions or diagnose problems.

In medicine, for example, doctors have to be careful. If a physician just read a paper on a rare autoimmune disorder, they might start seeing the symptoms of that disorder in every patient they treat for the next week. This is sometimes called "medical student syndrome," but it’s really just frequency illusion in a white coat.

It also plays a massive role in how we perceive news and social trends.

If you read one article about a "rising crime wave" in a specific neighborhood, your brain will start cherry-picking every news snippet that supports that narrative. You might ignore the fifty other stories about crime rates dropping or staying flat. You’re not being "objective." You’re just caught in a loop of noticing what you’ve already been primed to see.

💡 You might also like: Is a 4 qt air fryer actually enough? The truth about capacity and counter space

Digital echoes and the algorithm trap

Here is where it gets messy. In the 90s, when the term was coined, the phenomenon was purely psychological. Today, it's fueled by code.

If you search for "Baader-Meinhof complex" on Google, you are going to see ads or articles about it. This isn't just your brain's frequency illusion; it's the actual frequency increasing.

The algorithm "primes" you.

When people talk about their phones "listening" to them, it’s often a mix of two things:

- Real data tracking (scary, but real).

- The Baader-Meinhof complex.

You might mention a specific brand of sparkling water in conversation. Later that day, you see an ad for it. Maybe the ad was always there, but because you just spoke about it, your brain flagged it as "important" for the first time. Or, maybe the algorithm knew you were likely to want that water based on your GPS location at the supermarket. It’s a feedback loop where psychology meets technology.

Is it a bad thing?

Not really. It’s actually a sign your brain is working well. It shows you’re learning.

If you never experienced the Baader-Meinhof complex, it would mean your brain isn't updating its "importance" list. You’d be stuck in a static world where new information never integrates into your daily awareness.

However, it becomes a problem when it fuels "patternicity"—the tendency to find meaningful patterns in meaningless noise. This is the bedrock of conspiracy theories. If you start looking for "coded messages" in the news, you will find them. Not because they are there, but because your brain is a world-class pattern-matching machine that doesn't know when to quit.

Breaking the loop

So, how do you handle it when you feel like the world is suddenly shouting a specific word or brand at you?

👉 See also: How to Color Correct Under Eye Circles Without Looking Like You’re Wearing a Mask

First, acknowledge the "prime." Ask yourself: "Did I just learn about this recently?" If the answer is yes, you're likely just experiencing the illusion.

Second, look for the "dogs that don't bark." This is a classic Sherlock Holmes reference. To get an objective view, you have to look for the instances where the thing isn't happening.

If you think everyone is wearing neon green suddenly, start counting the people who are wearing literally any other color. You’ll quickly realize the neon green people are a tiny minority. You’ve just been ignoring the sea of beige and blue.

How to use this to your advantage

You can actually "hack" your brain using the Baader-Meinhof complex.

- Language Learning: When you learn a new vocab word, intentionally look for it in articles or subtitles. Once you "prime" your brain, you’ll start catching it in natural conversation much faster.

- Networking: If you're trying to get into a new industry, immerse yourself in the terminology. Your brain will start noticing opportunities, names, and news stories related to that industry that you previously would have skimmed over.

- Mindfulness: If you prime yourself to look for "small moments of kindness" during your commute, you will genuinely start to feel like the world is a nicer place. You aren't changing the world; you're just changing what your filter lets through.

The bottom line

The Baader-Meinhof complex is a reminder that we don't see the world as it is; we see the world as we are. Our interests, our recent experiences, and our new knowledge act as a lens.

Next time you see that obscure 1970s car three times in one hour, don't worry about the Illuminati or a glitch in the Matrix. Just realize your brain has a new favorite toy and it’s showing it off.

Actionable Steps

- Audit your "coincidences": The next time you experience the illusion, write down exactly when you first learned the new information. Usually, you'll find the "coincidence" happened within 24–48 hours of the initial exposure.

- Challenge the frequency: If you feel like a trend is "taking over," spend five minutes looking for data or statistics that contradict that feeling. This helps reset your confirmation bias.

- Intentional Priming: Pick a positive "target" today—like people wearing hats or the sound of laughter. Notice how often it occurs once you've decided to look for it. It’s a great way to realize how much control you have over your own daily perception.

References & Sources

- Zwicky, A. (2005). "Just Between You and me." Language Log.

- The "Frequency Illusion" study, Stanford University Department of Linguistics.

- Pioneer Press (1994) Archives regarding the original "Baader-Meinhof" reader submission.

- Cognitive Bias Codex research on confirmation bias and selective attention.