You’ve probably seen the book on a shelf or a syllabus. It looks like any other memoir. But here is the thing: Martin Luther King Jr. never actually sat down to write an autobiography.

He didn't have time. He was too busy being arrested, leading marches, and trying to stay alive. So, if he didn't write it, what exactly are you holding when you pick up a copy of The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr?

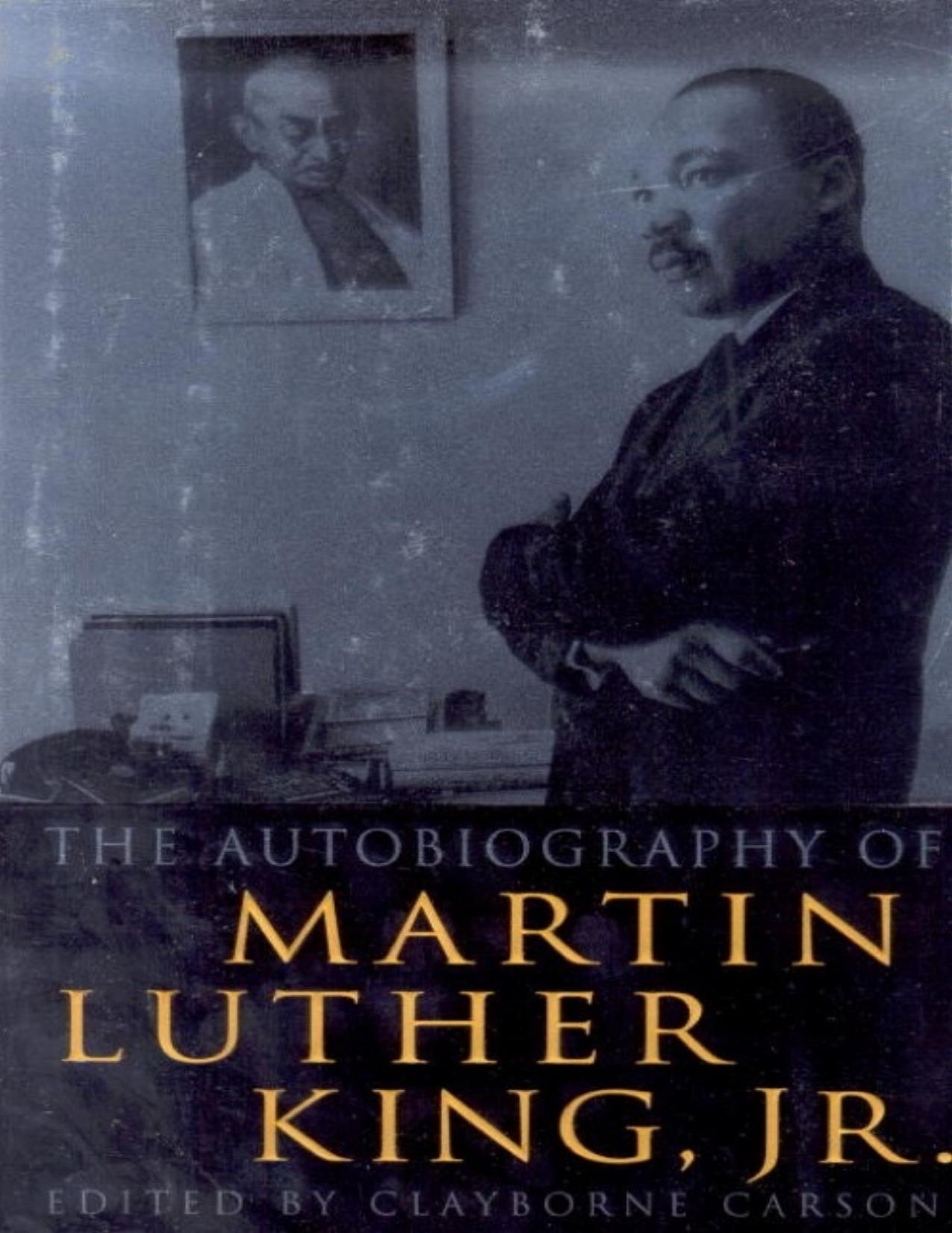

Basically, it’s a literary miracle. It was assembled long after his 1968 assassination by a historian named Clayborne Carson. In 1985, Coretta Scott King approached Carson with a massive mountain of King’s papers—letters, diary entries, speeches, and unfinished manuscripts—and asked him to weave them into a single, cohesive life story.

It worked.

The result is a "first-person" narrative that feels incredibly intimate, even though the "author" wasn't there to sign off on the final proof. It’s King’s voice, curated. And honestly, it’s probably the most honest look at the man we have, because it bypasses the "sanitized" version of King we usually get in history books.

The Myth of the "Easy" Nonviolence

Most people think King’s commitment to nonviolence was just a natural part of his personality. Like he was just a "nice guy" who didn't want to fight.

That’s totally wrong.

In the book, King is remarkably open about his "pilgrimage to nonviolence." It wasn't an overnight thing. He talks about growing up in Atlanta and feeling a "simmering fire" of resentment against the Jim Crow South. He wasn't born a pacifist; he was a smart, angry kid who saw the world was broken.

He actually struggled with the idea of loving his enemies. I mean, wouldn't you?

✨ Don't miss: Franklin D Roosevelt Civil Rights Record: Why It Is Way More Complicated Than You Think

The Gandhi Connection

King didn't just wake up and decide to be like Gandhi. He had to be convinced. During his time at Crozer Theological Seminary, he was actually quite skeptical of the power of love in social reform. He thought it worked for individuals, but not for groups or nations.

It took a trip to India and a deep dive into Thoreau’s Civil Disobedience to change his mind. The autobiography shows us a man who was intellectually wrestling with these ideas. He wasn't a saint on a pedestal; he was a scholar trying to find a tool that actually worked to break a system of oppression.

What He Really Thought About Malcolm X

If you rely on social media memes, you probably think King and Malcolm X were total opposites who hated each other.

The autobiography adds a lot of nuance here. King didn't "hate" Malcolm. He disagreed with his methods, sure. He famously called Malcolm’s rhetoric "fiery, demagogic oratory" that would "bring nothing but grief."

But there was respect there.

King acknowledged that Malcolm was a victim of the same system they were both trying to tear down. He saw Malcolm as a product of the "despair" of the urban North—a place King himself struggled to organize later in his life.

The "Letter from Birmingham Jail" in Context

We all know the famous quotes from the letter. But reading it within the flow of his life story changes how it hits.

By the time he’s in that cell in 1963, King is under immense pressure. He isn't just fighting white supremacists; he's being criticized by other Black leaders for being "too slow" and by white "moderates" for being "too radical."

🔗 Read more: 39 Carl St and Kevin Lau: What Actually Happened at the Cole Valley Property

The letter wasn't just a philosophical essay. It was a roar of frustration. He was tired of being told to "wait."

"For years now I have heard the word 'Wait!' It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity. This 'Wait' has almost always meant 'Never.'"

When you read this in the autobiography, you feel the weight of the bars. You feel the isolation. It’s not a polished speech; it’s a man defending his very existence to people who claimed to be his allies but wouldn't stand with him.

The Darker, Later Years

The version of King we celebrate on the holiday usually stops at the "I Have a Dream" speech in 1963. The autobiography doesn't let you off that easy.

The later chapters deal with the "Death of Illusions."

King’s move to Chicago was a wake-up call. He found that the racism in the North was, in many ways, more "vicious" and "hostile" than what he faced in Alabama. He saw that changing laws (like the Civil Rights Act) didn't automatically change lives if people were still trapped in slums and poverty.

The Vietnam War and the Radical Shift

This is the part of King’s life that most school curriculums skip over. He became a radical critic of the Vietnam War. He started talking about a "Poor People’s Campaign."

He realized that you couldn't solve racism without talking about capitalism and militarism. This made him incredibly unpopular. By 1967, his approval ratings were tanking. Even his own organization, the SCLC, was worried he was going too far.

💡 You might also like: Effingham County Jail Bookings 72 Hours: What Really Happened

The autobiography shows a man who was increasingly lonely in his convictions. He knew the "dream" had turned into a "nightmare" for many, and he was willing to lose his popularity to say so.

The Flaws and the Humanity

Honestly, the best thing about this book is that it doesn't try to hide King’s doubts.

He talks about his "brush with death" after being stabbed in Harlem by Izola Ware Curry. He reflects on the "violence of desperate men" and his own fears for his family.

There’s a vulnerability here that’s often lost in the monuments. He wasn't fearless. He was terrified, but he kept going anyway. That’s the definition of courage, right?

Why You Should Read It Now

We live in a time of massive polarization. Everyone likes to claim King for their side of the argument.

But if you actually read his words—the ones Carson meticulously stitched together—you realize King doesn't fit into a neat political box. He was a revolutionary. He was a preacher. He was a father who missed his kids.

Actionable Insights from the Text

If you want to apply King's philosophy today, the autobiography offers a few clear steps:

- Differentiate between "Negative Peace" and "Positive Peace." King argued that the absence of tension (negative peace) isn't the same as the presence of justice (positive peace). Don't just aim for things to be quiet; aim for them to be right.

- Understand the "Myth of Time." Progress doesn't happen automatically. Time is neutral. It’s what you do with it that matters. Waiting for things to "get better on their own" is a losing strategy.

- Focus on the "Triple Evils." King identified racism, poverty, and militarism as interconnected. You can't truly fix one without addressing the others.

- Master the "Art of Negotiation." Nonviolence wasn't just about marching; it was about creating a crisis so intense that the "oppressor" was forced to negotiate. It was a tactical, strategic move.

The autobiography ends with "Unfulfilled Dreams." It’s a haunting finish because we know how the story ends in Memphis. But it also leaves the "work" in the reader's hands.

To truly engage with King's legacy, start by reading his actual letters. Look up the full text of his 1967 "Beyond Vietnam" speech at Riverside Church. Compare his early optimism in Montgomery with his late-stage warnings about "Black Power" and "White Backlash." Understanding the evolution of his thought is the only way to avoid the shallow, "hallmark card" version of his life.