If you look at an Austro Hungarian Empire map from 1914, it looks like a giant, multicolored inkblot spreading across the heart of Europe. It’s huge. It’s messy. It’s honestly a bit of a miracle it stayed together as long as it did. Most people see a relic of a dead monarchy, but if you’re trying to understand why a train ride from Vienna to Budapest feels so seamless or why borders in the Balkans are still so tense, that old map is your best friend.

It wasn't a country. Not really. It was a "Dual Monarchy," a bizarre political experiment where two different governments—one in Vienna and one in Budapest—shared a king, an army, and a foreign policy. But they didn't share much else.

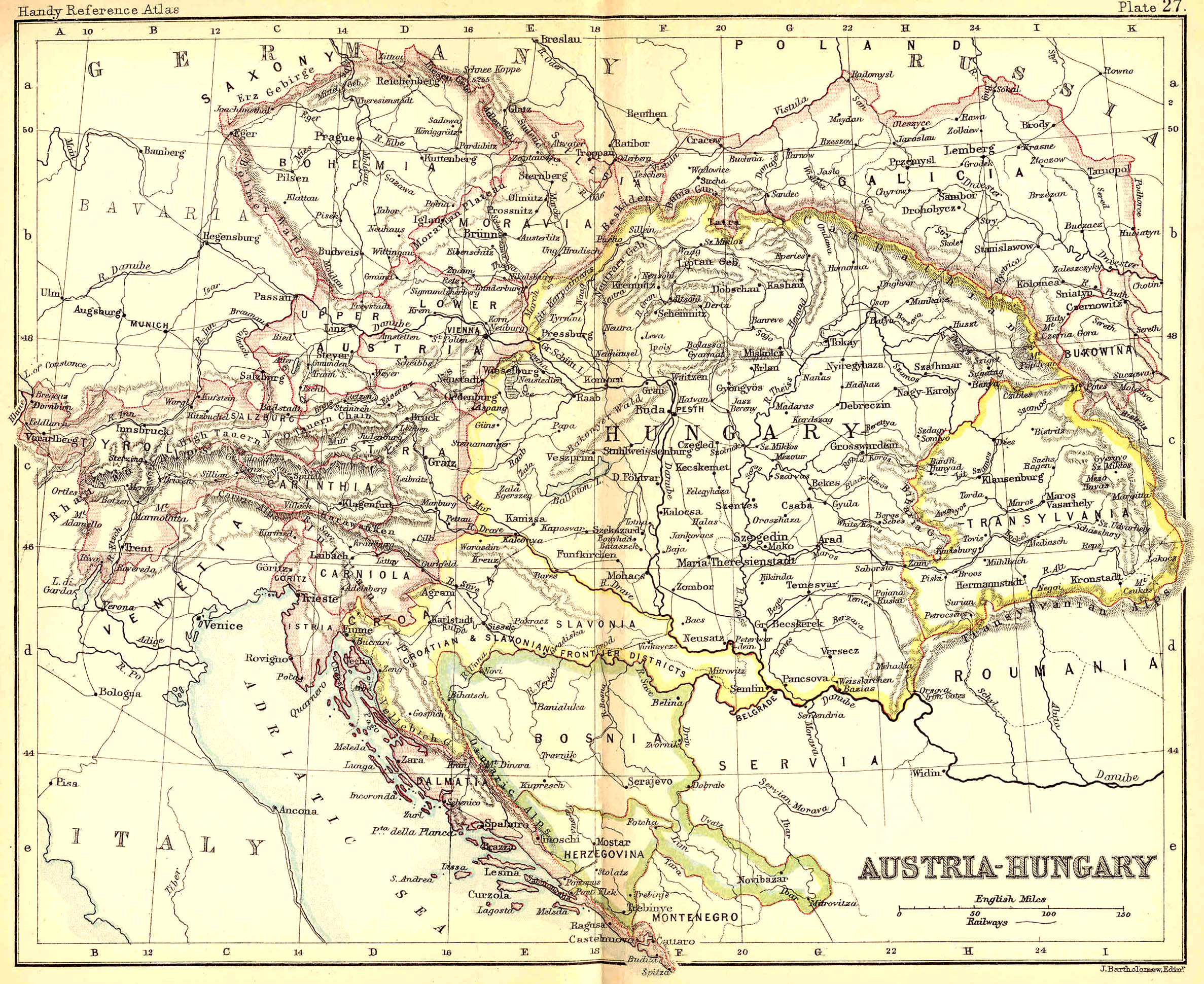

The Austro Hungarian Empire map covers what is now thirteen different countries. Think about that. You've got parts of Italy, Poland, Ukraine, Romania, and the entire Czech Republic tucked inside those borders. It was a sprawling, multi-ethnic jigsaw puzzle held together by the aging Emperor Franz Joseph and a very thick layer of bureaucracy.

The Weird Geography of the Dual Monarchy

Most people think of the empire as just Austria and Hungary. Wrong.

The map was actually split into two main parts with names that sound like something out of a fantasy novel: Cisleithania and Transleithania. Basically, "this side of the River Leitha" and "that side of the River Leitha."

Austria got the "this side" part, which included places like Bohemia (Prague) and even a thin strip of land along the Adriatic coast known as the Austrian Littoral. Hungary got the other side, ruling over what we now call Slovakia, Croatia, and Transylvania. Then you had Bosnia-Herzegovina, which was managed by both like a shared backyard that neither side could agree on.

It was a nightmare to govern.

Imagine trying to print a map where every town has three names. You had Lemberg (German), Lwów (Polish), and Lviv (Ukrainian). All the same place. If you were a postal worker in the 1890s, you probably deserved a raise every single week. This linguistic chaos is exactly why the Austro Hungarian Empire map is so fascinating to historians like Pieter Judson, who argues in The Habsburg Empire: A New History that the empire wasn't actually "doomed" by this diversity, but rather defined by it.

💡 You might also like: Lava Beds National Monument: What Most People Get Wrong About California's Volcanic Underworld

Why the Borders Looked So Strange

Ever notice how the borders on an Austro Hungarian Empire map don't follow mountain ranges or logical geographic lines? They were the result of centuries of royal marriages and messy inheritance laws. The Habsburgs had a famous motto: Bella gerant alii, tu felix Austria nube. It means "Let others wage war; you, happy Austria, marry."

They literally wedded their way into owning half of Europe.

By the time the map reached its peak size, it was an economic powerhouse. The empire had the fourth-largest machine-building industry in the world. They were exporting sugar, grain, and sophisticated Skoda artillery pieces. But the geography was working against them. While the British could sail the oceans, the Austro-Hungarians were landlocked on three sides. Their only real outlet to the sea was the port of Trieste (now in Italy) and Fiume (now Rijeka, Croatia).

This tiny coastline was their lifeline. It’s why you see grand, Viennese-style architecture in the middle of a Mediterranean port. If you walk through Trieste today, you’ll see the Piazza Unità d'Italia—it looks exactly like a square in Vienna, just with palm trees and a view of the Adriatic.

The 1914 Flashpoint: Bosnia and the Map’s Collapse

The most controversial part of the Austro Hungarian Empire map was the bottom-left corner: Bosnia and Herzegovina. Austria-Hungary "occupied" it in 1878 and then "annexed" it in 1908. This move royally pissed off Serbia and Russia.

It was a geopolitical land grab that backfired spectacularly.

When Archduke Franz Ferdinand went to Sarajevo in June 1914, he was visiting the empire’s newest, most unstable province. We all know what happened next. The map didn't just change; it shattered.

📖 Related: Road Conditions I40 Tennessee: What You Need to Know Before Hitting the Asphalt

By 1918, the empire was gone.

The Treaty of Saint-Germain and the Treaty of Trianon literally took a pair of scissors to the Austro Hungarian Empire map. Hungary was the biggest loser, losing 72% of its territory. To this day, you’ll find "Greater Hungary" stickers on cars in Budapest. People are still salty about a map that was redrawn over a hundred years ago. It’s not just history; it’s a living grievance.

How to Read an Empire Map Like an Expert

If you're looking at a vintage map, pay attention to the railways. The Habsburgs were obsessed with trains. They built a radial system where almost all tracks led back to Vienna or Budapest. This is why, even today, it’s often easier to get a train from Prague to Vienna than it is to get from Prague to a neighboring city in a different direction.

The infrastructure was designed to pull the periphery toward the center.

Also, look for the "Military Frontier." This was a weird buffer zone on the southern edge of the map, designed to keep the Ottoman Empire out. For centuries, this area was under direct military rule, separate from the civil administration. The people living there were basically permanent soldiers. This legacy of "borderland culture" is a big reason why that specific region has such a distinct, often martial, identity.

Common Misconceptions About the Borders

People usually think the empire was a "prison of nations." That’s a bit of an oversimplification.

While the Hungarians were pretty strict about "Magyarization" (forcing everyone to speak Hungarian), the Austrian side of the map was actually quite progressive for its time. They had laws protecting the rights of different ethnic groups to use their own languages in schools and local government.

👉 See also: Finding Alta West Virginia: Why This Greenbrier County Spot Keeps People Coming Back

It wasn't perfect, but it wasn't a North Korea-style lockdown either.

Another myth? That the empire was a crumbling "Old Man of Europe." Economically, it was growing. The population was booming. The Austro Hungarian Empire map wasn't failing because it was poor; it was failing because the people living inside it started wanting their own maps. National identity became a stronger drug than loyalty to a distant Emperor.

The Ghost Map: Where to See it Today

You don't need a time machine to see the empire. You just need a plane ticket.

Go to Lviv, Ukraine. Go to Timișoara, Romania. Go to Trento, Italy. In all these places, you’ll see the same yellow-painted government buildings (Habsburg Yellow was a specific shade), the same street layouts, and the same coffee house culture.

The Austro Hungarian Empire map exists as a "ghost map" beneath the modern borders of Europe. When the EU created the Schengen Area, they essentially recreated the old Habsburg map—a space where you could travel from the Alps to the Carpathians without showing a passport.

Actionable Steps for Historians and Travelers

If you’re genuinely interested in tracing this map for yourself, don't just look at a JPEG on Wikipedia.

- Visit the Map Collection at the Austrian National Library: They have the Josephinische Landesaufnahme, which is a terrifyingly detailed set of hand-drawn military maps from the late 1700s.

- Use the Mapire Website: This is an incredible tool that overlays historical Habsburg maps onto modern Google Maps. You can see exactly what stood where your favorite Starbucks is now.

- Trace the Railways: If you're a traveler, try the "Imperial Route." Take the train from Krakow to Vienna to Trieste. You’ll see the architectural DNA of the empire shifting from Slavic to Germanic to Italian, all held together by that specific Habsburg aesthetic.

- Read the Literature: To understand the feel of the map, read The Radetzky March by Joseph Roth. It’s the best book ever written about how it felt to live in a country that was slowly disappearing.

The Austro Hungarian Empire map is a reminder that borders are never permanent. They’re just lines we draw in the dirt until someone else comes along with a bigger eraser. Understanding where those lines used to be is the only way to make sense of why Europe looks the way it does today.

To get the most out of your research, start by identifying a specific region on the map—like Galicia or the Sudetenland—and look for local archives. These "peripheral" areas often tell a much more interesting story than the capital cities ever could. Focus on the transition years between 1910 and 1923 to see how the world’s most complex puzzle was pulled apart and put back together in a shape that barely fit.