Everyone thinks they know the story. A bunch of geniuses in lab coats huddled in the New Mexico desert, Oppenheimer quoting scripture, and suddenly—boom—the world changed. It's a clean narrative. It's also mostly a caricature. If you look at the actual history of making the atomic bomb, it wasn't just a "eureka" moment in a physics lab. It was the largest industrial gamble in human history. Honestly, it was more about plumbing, grit, and massive factories than it was about abstract blackboard equations.

The scale was stupidly large.

By 1945, the Manhattan Project was consuming nearly 1% of the entire US economy. Think about that. We aren't talking about a small research team; we’re talking about 130,000 people. Most of them had absolutely no clue what they were building. They were just turning valves or monitoring dials in massive facilities like Oak Ridge or Hanford.

💡 You might also like: The Phone Watch Charging Station: Why Your Desk Still Looks Like a Disaster

The Raw Materials Problem (It's Harder Than You Think)

You can't just dig up a rock and have a weapon. That’s the first big misconception. The physics of making the atomic bomb is relatively straightforward on paper, but the chemistry and engineering are a nightmare.

Nature is stubborn.

Uranium found in the ground is mostly $U-238$. It’s stable. It’s boring. It won't explode. Only about 0.7% of it is $U-235$, the fissile stuff you actually need. Separating those two is basically impossible because they are chemically identical. You can't use a chemical reaction to peel them apart. You have to rely on the tiny, tiny mass difference between them.

Oak Ridge and the "Sieve" Method

To solve this, they built K-25 in Tennessee. At the time, it was the largest building under one roof in the world. They used gaseous diffusion. Basically, they turned uranium into a highly corrosive gas called uranium hexafluoride and forced it through miles of silver-zinc barriers.

The holes in these barriers were microscopic.

The $U-235$ atoms are just a tiny bit lighter, so they move slightly faster. If you do this thousands of times—literally through thousands of stages—you eventually get enough enriched material. It was a brutal, inefficient, and incredibly expensive process. General Leslie Groves, the guy running the show, didn't even know if it would work. He just built three different types of factories at once, hoping one would hit the jackpot.

The Plutonium Shortcut

Then there's the other path. Plutonium.

This didn't even exist in significant quantities in nature. Scientists had to create it. At the B Reactor in Hanford, Washington, they bombarded $U-238$ with neutrons. This transformed the uranium into a brand-new element: Plutonium-239.

It was messy. It was radioactive. It required remote-controlled robots and massive concrete "canyons" to handle the chemistry because the radiation would kill a human in seconds. While the uranium bomb (Little Boy) was a "gun-type" design—literally firing one piece of uranium into another—the plutonium bomb (Fat Man) was way more complex. You had to compress a solid sphere of plutonium using perfectly timed explosives. If your timing was off by a microsecond?

The whole thing would just fizzle.

The Los Alamos Pressure Cooker

While the factories in Tennessee and Washington were churning out the fuel, the "brain trust" was stuck on a mesa in New Mexico. This is the part Hollywood loves. Los Alamos.

It wasn't a spa. It was a high-pressure, muddy, chaotic mess of a town.

Oppenheimer had to manage a collection of the world's most massive egos. You had Richard Feynman, who spent his free time picking the locks of top-secret safes just to show how bad security was. You had Edward Teller, who was already obsessed with a "Super" (the hydrogen bomb) and didn't want to work on the "small" fission project.

Why the "Gun" Design Was a Secret Risk

Most people don't realize that the Hiroshima bomb was never even tested before it was dropped. The scientists were so confident in the "gun-type" uranium design that they didn't think a test was necessary. It was essentially a cannon barrel that fired a "slug" of uranium into a "target" of uranium. When they hit, they reached critical mass.

✨ Don't miss: How Do You Get Nudes on Snapchat? The Honest Reality of Risks and Consent

Simple. Brutal.

But the plutonium bomb was a different beast. Because plutonium is so much more reactive, a gun-type design would cause it to melt before it actually exploded. It would pre-detonate. That's why they had to invent "implosion." They had to surround a plutonium core with "lenses" of high explosives—some fast-burning, some slow-burning—to create a perfectly symmetrical shockwave.

It’s like trying to crush an orange so perfectly that it shrinks into a marble without any juice leaking out between your fingers.

The Logistics Nobody Talks About

We focus on the scientists, but making the atomic bomb was a triumph of the American middle class.

- Security: Tens of thousands of workers were told they were helping win the war, but if they talked about their jobs, they’d be in a federal prison.

- Silver: There was a shortage of copper for the massive electromagnets used in uranium separation. So, the Treasury Department "loaned" the project 14,000 tons of silver from the US vaults. It was eventually all returned.

- Safety: They were dealing with materials no one understood. At Los Alamos, Louis Slotin eventually died because a screwdriver slipped during an experiment with a plutonium core, causing a massive burst of radiation. He stayed at his post to knock the core apart and save his colleagues.

The Ethics and the Aftermath

By 1944, many of the scientists realized the German project—their original reason for existing—had stalled. Suddenly, the moral landscape shifted.

✨ Don't miss: Why an Airplane Drone with Camera is Actually Better Than a Quadcopter

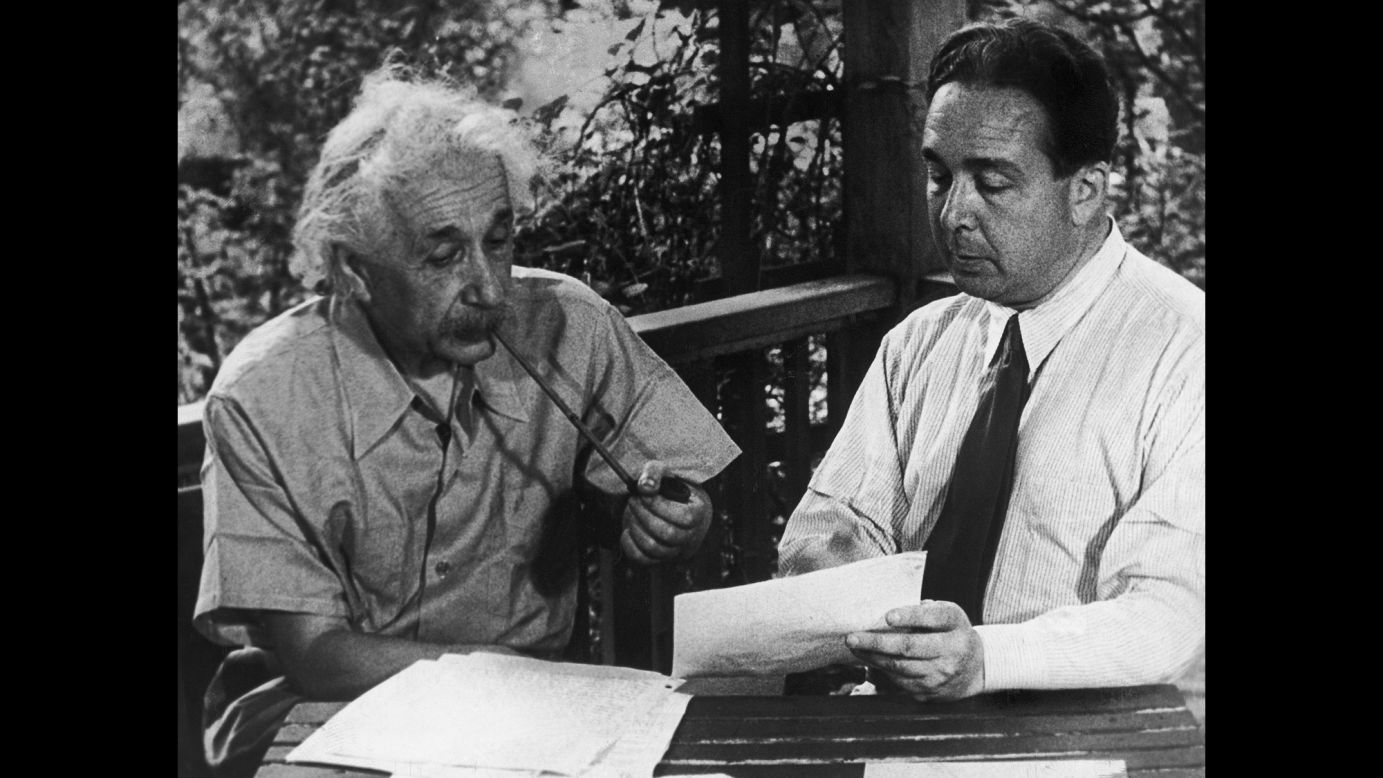

Leo Szilard, the man who first conceived of the nuclear chain reaction, started a petition to stop the bomb's use against Japan. He was ignored. The momentum of a two-billion-dollar project is hard to stop. Once the machine started moving, it had its own logic.

Was it necessary? That's a debate that will never end. Military leaders like Curtis LeMay argued the firebombing of Japanese cities was already doing the job. Others, like Secretary of War Henry Stimson, believed only a "total" weapon would force a surrender without a million-man invasion of the Japanese mainland.

Real Insights for History Buffs

If you want to truly understand the technical reality of this era, don't just watch movies. Look at the primary sources.

- Read the Smyth Report: Released just days after the bombings in 1945, this was the first official account of the project. It’s surprisingly technical and was used to tell the world, "Yeah, we did this, and here is (some of) how."

- Visit the Sites: You can actually tour parts of Oak Ridge and Hanford now. Seeing the scale of the B Reactor in person makes the "science" feel much more like "heavy industry."

- Study the "Franck Report": This was a document written by physicists at the University of Chicago arguing for a non-combat demonstration of the bomb before using it on a city. It’s a haunting look at the scientists trying to put the genie back in the bottle.

Practical Steps to Learn More

If you're looking to dive deeper into the actual mechanics of making the atomic bomb, start with these specific actions:

- Analyze the Rhodes Text: Read The Making of the Atomic Bomb by Richard Rhodes. It is widely considered the definitive technical and human history of the project. It won a Pulitzer for a reason.

- Explore the "Atomic Heritage Foundation" Digital Archives: They have hundreds of oral histories from the "hidden" workers—the janitors, the secretaries, and the technicians who actually ran the machines.

- Examine the Declassified Maps: Look at the original layouts of Los Alamos. You’ll see it wasn’t a sleek lab; it was a series of slapped-together wooden barracks that were freezing in the winter and dusty in the summer.

- Research the "Alsos Mission": Look into the secret US intelligence mission that followed Allied front lines into Europe to see how close the Nazis actually got (spoiler: they weren't even close).

The real story isn't just a flash of light in the desert. It's the story of how a nation transformed its entire industrial base to turn a theoretical concept into a terrifying reality in less than four years. It was a feat of engineering that hasn't been matched since, for better or worse.