France was broke. Not "I should skip my morning latte" broke, but "the entire kingdom is sinking under a mountain of debt" broke. By 1787, King Louis XVI was staring at a financial black hole that threatened to swallow the Bourbon dynasty whole. He needed money, and he needed it fast. His solution? The Assembly of the Notables. It sounds fancy. It sounds prestigious. In reality, it was a desperate political gamble that backfired so spectacularly it basically greased the wheels for the French Revolution.

Most people think the Revolution started with the Bastille. Honestly, it started here.

The Assembly of the Notables wasn't a regular parliament. It was a hand-picked group of the kingdom's "finest"—nobles, clergy, and a few high-ranking officials. Louis thought that if he hand-selected the guys in the room, they’d just nod along to his tax hikes. He was wrong. Very wrong.

The Setup: Why Louis XVI Called the Notables

The math was simple and terrifying. France had spent a fortune helping out in the American Revolution. While it was great to stick it to the British, it left the French treasury empty. Charles Alexandre de Calonne, the Controller-General of Finance, realized that the current system was a joke. The poor were taxed until they bled, while the rich—the nobility and the Church—paid almost nothing.

Calonne knew he couldn't just pass a new tax through the Parlements (the regional courts). Those guys were notoriously stubborn. So, he suggested reviving an old, mostly forgotten trick: calling an Assembly of the Notables.

It hadn't been done since 1626.

The idea was to bypass the pesky courts by getting the most influential men in the country to endorse a "territorial subvention." That’s a fancy way of saying a land tax that applied to everyone, even the dukes and bishops. Calonne figured that if the Notables agreed, the public would see it as a patriotic sacrifice.

He misjudged his audience.

The Men in the Room

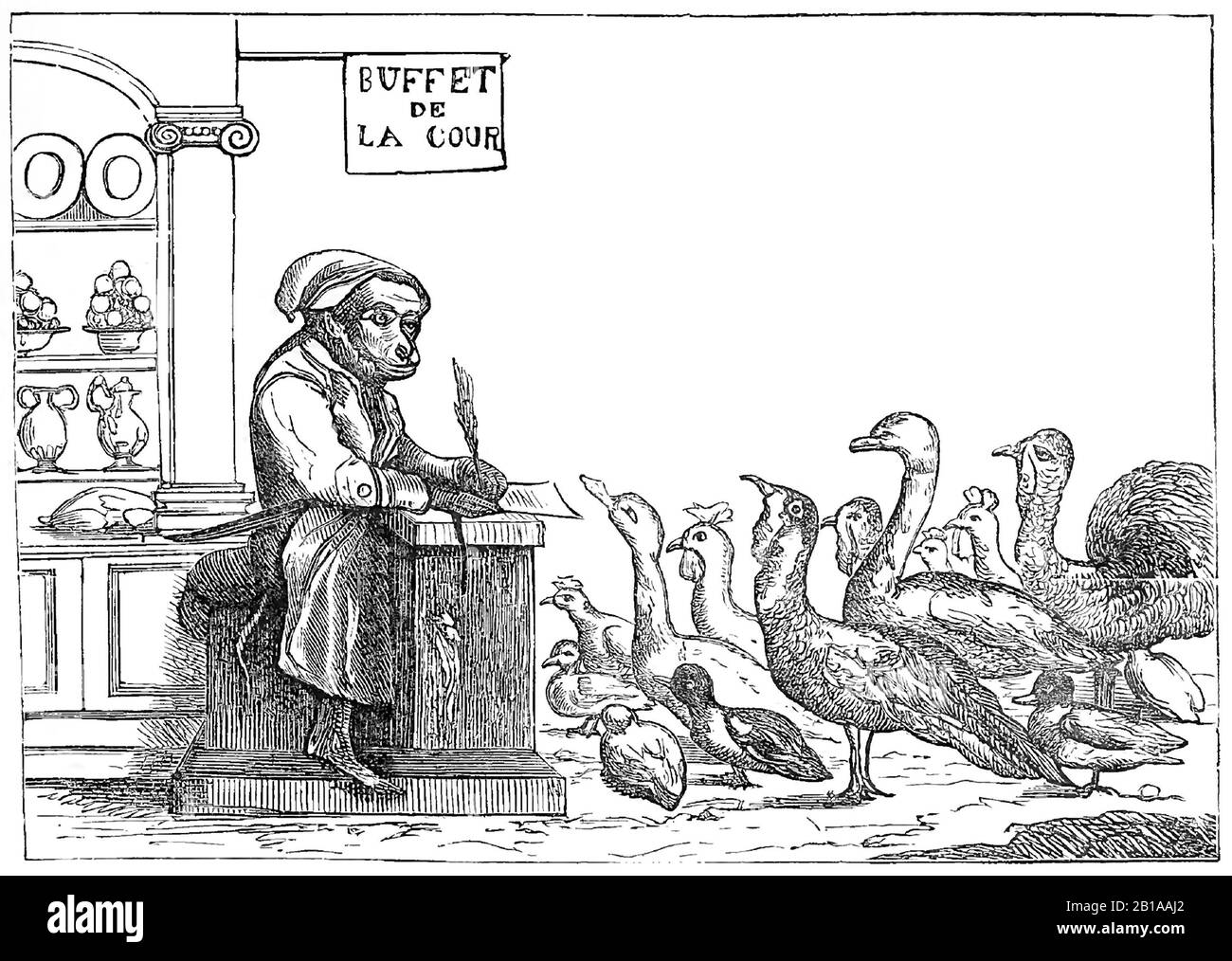

When the 144 notables gathered at Versailles in February 1787, they weren't in a mood to give away their money. You had seven Princes of the Blood, 36 dukes and peers, and a smattering of archbishops. These were the people who benefited most from the status quo.

👉 See also: Patrick Welsh Tim Kingsbury Today 2025: The Truth Behind the Identity Theft That Fooled a Town

Calonne opened the session with a speech that was basically a confession. He admitted the deficit was huge—about 112 million livres. He told them the only way out was to ditch their tax exemptions.

The reaction? Pure hostility.

They didn't just hate the tax; they hated Calonne. They suspected he had been cooking the books. They called him "Monsieur Déficit." It was a mess.

Why the Assembly of the Notables Refused to Budge

You might think they were just being greedy. That’s part of it, sure. But it was also about power. The Notables argued that they didn't have the legal authority to approve new taxes. They claimed that only the Estates-General—a massive representative body that hadn't met in over a century—could do that.

This was a brilliant tactical move. By calling for the Estates-General, the Notables looked like they were defending the "rights of the nation" against a tyrant, when they were actually just protecting their own wallets.

Louis XVI was stunned. He expected a rubber stamp; he got a rebellion.

He eventually fired Calonne and brought in Étienne Charles de Loménie de Brienne, the Archbishop of Toulouse. Brienne was actually one of the leaders of the opposition within the Assembly! But once he got into office and saw the actual account books, he realized Calonne was right. The country was doomed without that tax.

Brienne tried to pitch a slightly modified version of the same plan to the same group of people.

✨ Don't miss: Pasco County FL Sinkhole Map: What Most People Get Wrong

They still said no.

The Ghost of 1626

To understand why this was such a disaster, you have to look back at the history. When Richelieu called the Notables in 1626, he dominated them. The monarchy was ascending. By 1787, the monarchy was viewed as out of touch and incompetent. The Enlightenment had changed the way people thought about "notables" and "divine right."

The Assembly of the Notables ended up being a platform for the nobility to air their grievances. Instead of solving the debt, it highlighted the king’s weakness.

The Domino Effect

The Assembly was dismissed in May 1787. It had accomplished exactly nothing.

Well, that's not entirely true. It had accomplished one very big thing: it broke the illusion of absolute royal power. By failing to get the Notables to agree, Louis XVI showed the world that he couldn't control his own aristocracy.

The struggle then moved to the Parlements. When they also refused to register the taxes, the king tried to exile them. This led to riots, most notably the "Day of the Tiles" in Grenoble. Eventually, the pressure became so great that Louis was forced to do the one thing he feared most: summon the Estates-General for 1789.

We all know how that ended.

Common Misconceptions About the Notables

People often lump the Assembly of the Notables in with the Estates-General. They are totally different. The Notables were an advisory body picked by the king. The Estates-General was an elected body representing the three "estates" of society.

🔗 Read more: Palm Beach County Criminal Justice Complex: What Actually Happens Behind the Gates

Another big mistake is thinking the Notables were the "bad guys" and the king was the "good guy" trying to tax the rich. It’s more complicated. Many Notables actually wanted reform—they just wanted it on their terms. They wanted a say in how the money was spent. They wanted a constitutional monarchy, sort of like what Britain had.

Louis, meanwhile, wanted the money without giving up any control. It was a classic "immovable object meets irresistible force" scenario.

Actionable Insights: Lessons from a 200-Year-Old Failed Meeting

History isn't just about dead guys in powdered wigs. The failure of the Assembly of the Notables offers some pretty sharp lessons for modern leadership and governance.

- Transparency is non-negotiable. Calonne’s biggest mistake was hiding the depth of the crisis until it was too late. When he finally came clean, no one trusted his numbers. If you’re leading an organization through a crisis, you have to be honest about the stakes from day one.

- Don't bypass the process. Louis tried to take a shortcut by picking his own "voters." It blew up in his face. In any system, trying to circumvent established checks and balances usually just gives your opponents more ammunition.

- Optics matter. The Notables were able to paint themselves as heroes of the people because the King looked like a spendthrift. Even if your intentions are logically sound, if you lose the PR war, you lose the policy war.

- Understand the "Silent" Power. The Notables represented the "1%" of the 18th century. They had the most to lose, which made them the hardest to convince. Change rarely comes from the top down when the top is comfortable.

To really understand the French Revolution, stop looking at the guillotine for a second. Look at the meeting rooms of 1787. The Assembly of the Notables was the moment the old world realized it couldn't survive, but refused to change anyway.

If you're researching this for a project or just a deep dive into history, focus on the memoirs of the Comte de Mirabeau or the official records of Brienne’s ministry. They show a government that wasn't just broke—it was paralyzed.

For those looking to visit the sites of these events, the Hôtel des Menus-Plaisirs in Versailles is where a lot of this political drama unfolded. It’s often overshadowed by the main palace, but it's where the real power struggles happened.

The Assembly of the Notables remains a masterclass in how not to handle a national emergency. Louis XVI thought he was calling together his friends to save his crown. Instead, he invited the very people who would help dismantle it.

To explore more about the specific financial records that panicked the Notables, look into the Compte rendu au roi by Jacques Necker. It was the first time French royal finances were made public, and it set the stage for all the distrust that followed in 1787. Understanding that document is the key to understanding why the Notables were so skeptical of Calonne's later claims.