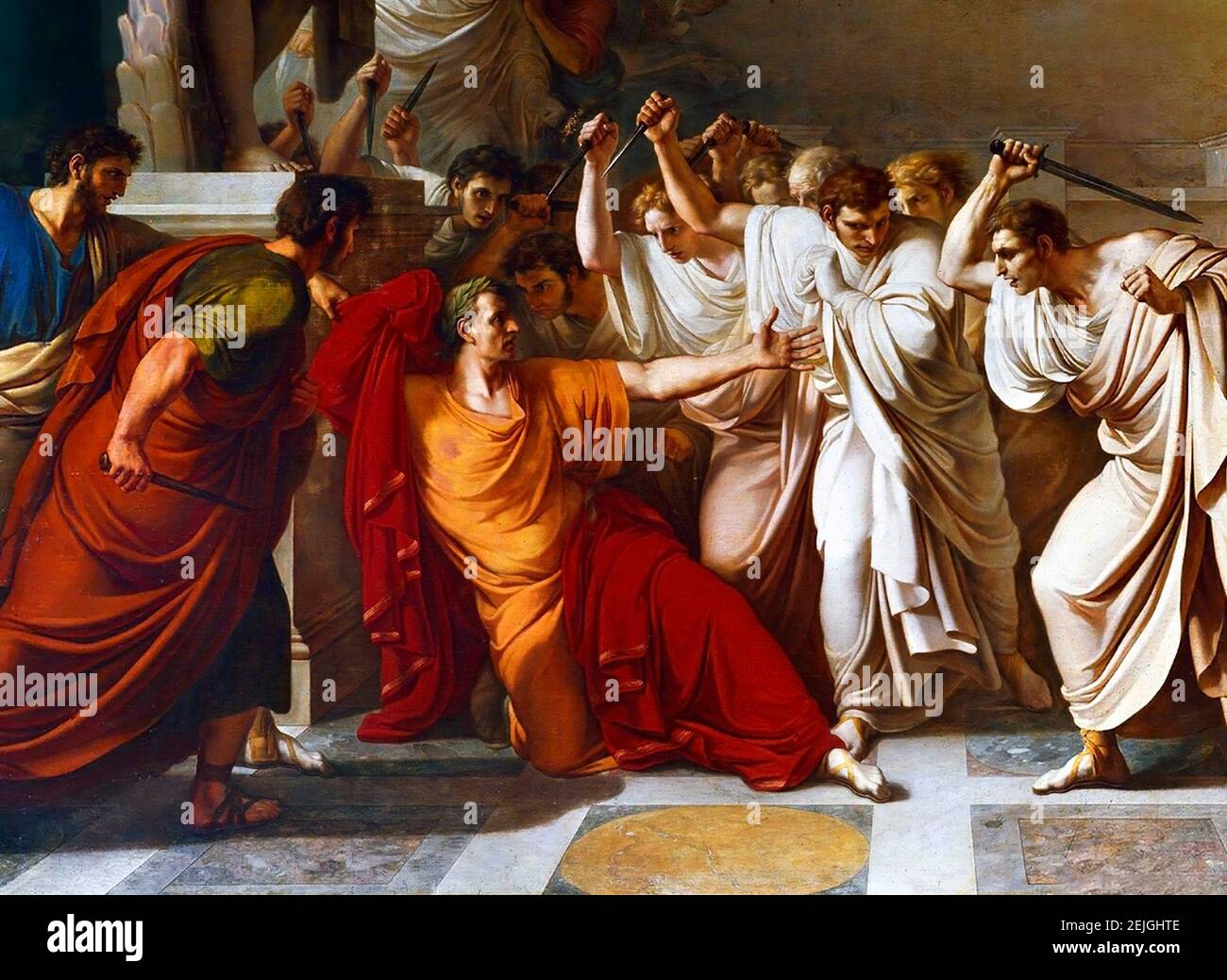

March 15, 44 BCE. It’s a date that basically every school kid knows, or at least they think they do. We’ve all seen the Shakespeare play. We’ve heard the "Et tu, Brute?" line a thousand times. But honestly, the real assassination of Julius Caesar was way messier, more desperate, and frankly more confusing than the movies make it out to be. It wasn't just a group of guys in clean white togas standing in a circle; it was a bloody, chaotic scramble in a temporary meeting hall that changed the entire course of Western civilization.

He was dead. In minutes.

The Senate wasn't even meeting in the actual Senate House (the Curia Hostilia) that day because it was being renovated. They were at the Theatre of Pompey. Think about the irony there. Caesar died at the base of a statue of Pompey the Great, his greatest rival, whom he had defeated in a brutal civil war years earlier. If you’re looking for a "poetic justice" moment in history, that’s probably the biggest one you’ll ever find.

Why They Actually Did It

People often think the conspirators—the "Liberators," as they called themselves—were just jealous. Some were. But for guys like Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus, it was deeper. They were terrified. Caesar had just been named Dictator Perpetuo (Dictator in Perpetuity). In the Roman Republic, "Dictator" was supposed to be a temporary job for emergencies. Making it permanent? That’s just a king by another name. And Romans hated kings. They had a literal phobia of them dating back centuries.

The tension wasn't just political; it was personal. Caesar was handing out honors, putting his face on coins, and sitting on a golden throne. He was acting like a god while the old-school aristocrats felt their power slipping away. They weren't fighting for "democracy" in the way we think of it today. They were fighting for their own right to run the show without one man calling all the shots.

The Assassination of Julius Caesar: A Play-by-Play of the Chaos

The morning of the Ides started with bad omens. Caesar’s wife, Calpurnia, allegedly had nightmares. A soothsayer named Spurinna told him to "beware the Ides of March." Caesar almost didn't go. But Decimus Brutus—not the famous Marcus Brutus, but a close friend Caesar actually trusted—convinced him to show up. Decimus basically teased him, asking if the great Caesar was really going to stay home because of a woman's dreams.

👉 See also: Why Trump's West Point Speech Still Matters Years Later

He went. He walked right into it.

Once he sat down, the conspirators crowded around him. Tillius Cimber pulled at Caesar’s robe, which was the signal. Servilius Casca struck first, but he was nervous and missed, only grazing Caesar’s neck or shoulder. Caesar grabbed Casca’s arm and shouted, "Casca, you villain, what are you doing?"

Then the rest piled on.

It wasn't a coordinated tactical strike. It was a panicked frenzy. They were hitting each other in the rush to stab him. Brutus was reportedly wounded in the hand by one of his own friends. Caesar fought back at first, but once he saw Brutus—a man he had treated like a son—he supposedly gave up. He pulled his toga over his head and fell. He was stabbed 23 times. Only one wound, a deep one to the chest, was actually fatal, according to the physician Antistius who performed what was essentially history's first recorded autopsy.

The Myth of "Et Tu, Brute?"

Let's address the elephant in the room. Caesar probably never said "Et tu, Brute?" That's Shakespeare. Ancient historians like Suetonius suggest he might have said nothing at all. Others claim he said, in Greek, "Kai su, teknon?" which means "You too, my child?" It sounds tender, but in the context of the time, it might have been a curse—sort of like saying, "You're next." We’ll never know for sure. The silence of a dying man is a lot more haunting than a scripted line.

✨ Don't miss: Johnny Somali AI Deepfake: What Really Happened in South Korea

The Aftermath Nobody Predicted

The Liberators thought that as soon as Caesar was dead, the Republic would just... wake up. They expected the Roman people to cheer in the streets. They didn't. They were horrified. Caesar was a populist. He’d given them land, grain, and hope.

Mark Antony, Caesar's right-hand man, gave a massive funeral oration that turned the tide. He showed the crowd Caesar's bloody, tattered robe. He read Caesar's will, which left money to every single Roman citizen. The city turned into a riot. The conspirators had to flee for their lives. Instead of saving the Republic, the assassination of Julius Caesar triggered another thirteen years of civil war.

- The Power Vacuum: With Caesar gone, his teenage grand-nephew Octavian (the future Emperor Augustus) arrived to claim his inheritance.

- The End of the Senate's Power: The very body that killed Caesar to save its relevance ended up losing almost all its power to Octavian.

- The Rise of the Empire: The Republic was dead. It just didn't know it yet.

What Most People Get Wrong

People often forget that Caesar was actually planning to leave Rome just three days later. He was heading east to invade Parthia (modern-day Iran/Iraq) to avenge a massive Roman defeat. If the conspirators hadn't acted on March 15, Caesar would have been away with his legions for years. He might have died in battle, or he might have come back so powerful that no one could have touched him.

The timing was a desperate, "now or never" move.

Also, it wasn't just "the senators" who killed him. There were about 60 conspirators, but many were Caesar's own "friends" and officers. This wasn't a clean break between enemies; it was a betrayal by his inner circle. That's why it stung so much. That's why it still resonates.

🔗 Read more: Sweden School Shooting 2025: What Really Happened at Campus Risbergska

Why This History Matters Today

You can't understand modern politics or power dynamics without looking at this moment. It's the ultimate case study in "unintended consequences." The Liberators had a clear goal: kill the tyrant, save the system. They achieved the first part and completely destroyed the second.

When you remove a central pillar of a system without a plan for what comes next, the whole roof caved in. Rome didn't return to a free state; it collapsed into an autocracy that lasted for centuries. It’s a reminder that political "solutions" involving violence rarely lead to the peace the perpetrators imagine.

Takeaway Lessons from the Ides

If you're looking to dive deeper into this or apply these historical insights to your own understanding of power, here is what you should focus on:

- Look at the Institutional Failures: Don't just focus on Caesar the man. Look at why the Roman Senate was so broken that it couldn't handle a figure like him. Systems often fail long before the "tyrant" arrives.

- Study the "Second Tier" Players: Names like Decimus Brutus and Lepidus are often ignored, but they were the ones who made the assassination possible. History happens in the margins.

- Read the Primary Sources (with a grain of salt): Check out Plutarch’s Life of Caesar or Suetonius’s The Twelve Caesars. They’re surprisingly readable, full of gossip, and show how the Romans themselves viewed the event. Just remember they were writing years after the fact with their own agendas.

- Analyze the Propaganda: Look at how Octavian used the "Divinity" of Caesar to cement his own power. It was the first modern PR campaign.

The assassination of Julius Caesar wasn't the end of a story; it was a violent pivot. It proved that you can kill a man, but you can't kill the momentum of a changing world. If you want to see the real impact, look at the ruins of the Roman Forum today. The Temple of Caesar still stands right in the middle, a permanent marker of where they burned his body and where the Republic finally took its last breath.

Visit the Largo di Torre Argentina in Rome if you ever get the chance. It's the site of the Theatre of Pompey where it actually happened. Today, it’s a cat sanctuary. There’s something strangely human and grounded about the fact that the spot where the most famous man in history was betrayed is now a place where stray cats nap in the sun. History is big, but it’s also very, very small.