Rome was a mess. By the time we get to 44 BCE, the old "Republic" was basically a ghost of its former self. You’ve probably seen the movies where a bunch of guys in bedsheets stab a guy in a theater, but the reality of the assassination of Julius Caesar was a lot messier, more desperate, and frankly, more confusing than Hollywood lets on. It wasn't just about "liberty." It was a high-stakes political gamble that backfired so spectacularly it ended up destroying the very thing the conspirators were trying to save.

He stayed too long. That’s the simplest way to put it. Caesar had just been named Dictator Perpetuo—dictator for life. In a city that absolutely loathed the idea of kings, that title was a massive, glowing target on his back.

Why the Ides of March actually mattered

Most people think the "Ides" is some spooky, cursed date. It's not. In the Roman calendar, the Ides was just the midpoint of the month. It happened every month. But on March 15, 44 BCE, it became the date of the most famous political hit job in history.

Why did they do it?

The conspirators, who called themselves the Liberatores, weren't just a random mob. These were elite senators. We’re talking about guys like Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus. Brutus is the interesting one because Caesar actually liked him. There’s a long-standing rumor—though most serious historians like Mary Beard or Adrian Goldsworthy treat it with a healthy dose of skepticism—that Brutus might have been Caesar’s illegitimate son. Caesar had a high-profile affair with Brutus’s mother, Servilia, years prior. Even if they weren't blood, the betrayal was deeply personal.

The Senate was terrified. They saw Caesar bypass their authority constantly. He was issuing edicts, minting coins with his own face on them (total king move), and wearing purple robes. To the Roman elite, purple was the color of royalty, and royalty was a one-way ticket to tyranny. They didn't just want him dead; they wanted to "restore the Republic."

The logistics of a Senate floor murder

The assassination of Julius Caesar didn't happen in the Senate House you see in the Roman Forum today. That building was being renovated. Instead, the Senate met in the Theater of Pompey.

It was a trap.

📖 Related: Trump New Gun Laws: What Most People Get Wrong

Caesar almost didn't go. His wife, Calpurnia, supposedly had nightmares. He was feeling under the weather. But Decimus Brutus—another "friend" who was secretly a lead conspirator—basically egged him on, telling him he’d look weak if he stayed home because of a woman's dreams.

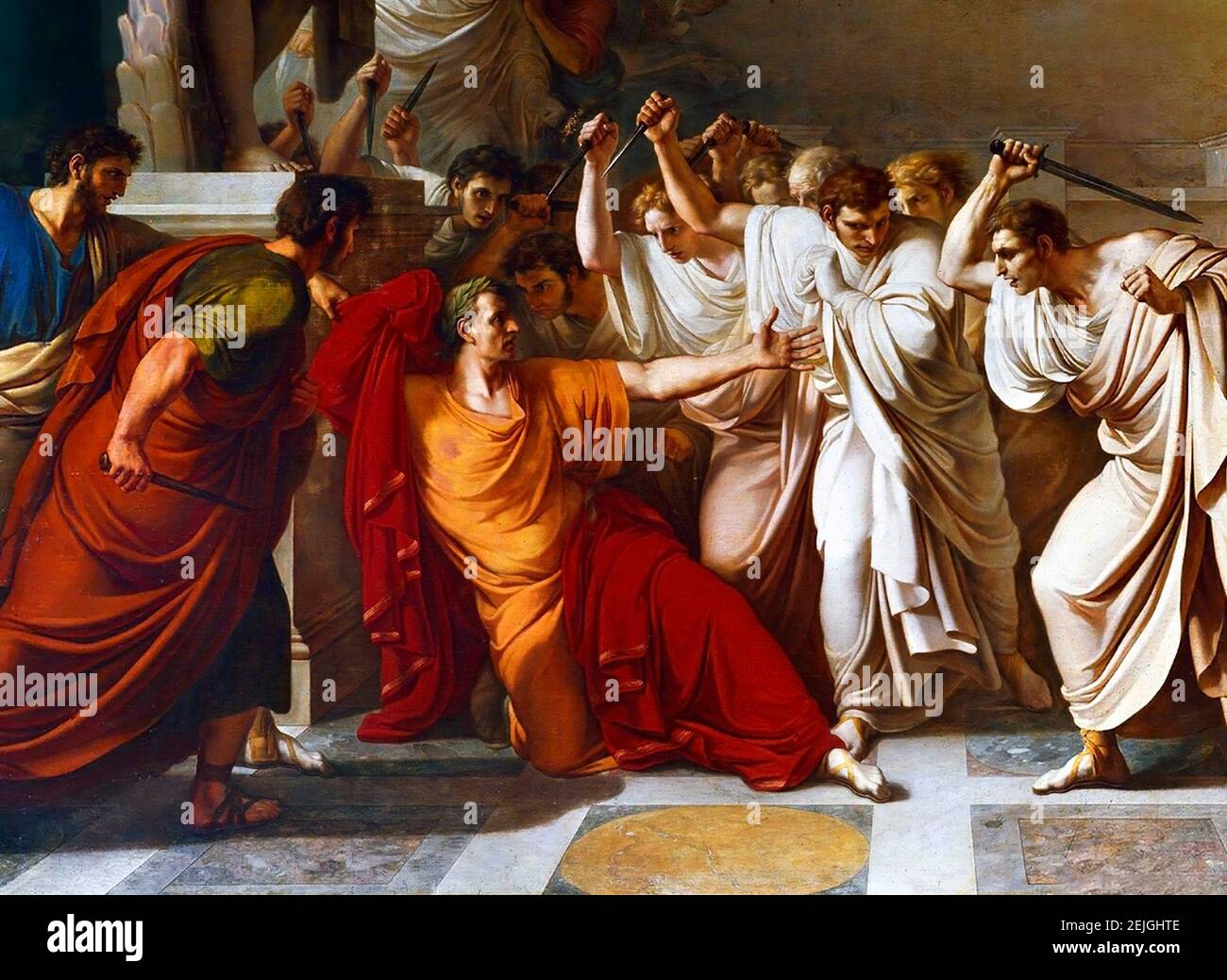

When he arrived, the senators surrounded him under the guise of presenting a petition for the recall of the exiled brother of Lucius Tillius Cimber. It was a classic pincer move. Cimber grabbed Caesar’s toga, pulling it down from his shoulders. This was the signal.

"Vile Casca, what are you doing?"

Those were Caesar's words (roughly translated from Suetonius) when Publius Servilius Casca Longus struck the first blow. Casca was nervous. He missed. He grazed Caesar’s shoulder or neck. Caesar, being a veteran soldier, fought back. He allegedly stabbed Casca through the arm with his stylus—a sharp metal pen.

Then the rest of them piled on.

It was chaos. Pure, bloody chaos. The conspirators were so frantic to get a piece of him that they actually ended up stabbing each other. Brutus got a wound in the hand. By the end, Caesar had 23 stab wounds. Only one, a deep puncture to the chest, was actually fatal, according to the physician Antistius who performed history’s first recorded autopsy.

He died at the base of a statue of Pompey the Great. Pompey had been his greatest rival. The irony is almost too heavy for a history book, but that’s where he fell.

👉 See also: Why Every Tornado Warning MN Now Live Alert Demands Your Immediate Attention

The myth of "Et Tu, Brute?"

Let’s be real: he probably didn't say it.

William Shakespeare gave us that line because it sounds great on stage. In reality, according to the Greek historian Plutarch, Caesar said nothing at all. He just pulled his toga over his head so he could die with some dignity.

Other accounts, specifically from Suetonius, suggest he might have said, "Kai su, teknon?" in Greek. That translates to "You too, child?" or "Even you, kid?" It sounds more like a disappointed father than a tragic hero. But even Suetonius admits that Caesar might have just groaned and died in silence. Words are hard when your lungs are filling with blood.

What most people get wrong about the aftermath

The conspirators thought the people would cheer. They thought they’d walk out into the streets, wave their bloody daggers, and everyone would shout, "Yay, freedom!"

They were wrong. Dead wrong.

The Roman public actually loved Caesar. He’d given them grain. He’d given them land. He’d entertained them with massive games. When Mark Antony gave his famous funeral oration (which was more of a political rally), he showed the crowd Caesar’s blood-stained, tattered toga. He read Caesar’s will, which left a significant amount of money to every single Roman citizen.

The city turned into a riot. The "Liberators" had to flee for their lives.

✨ Don't miss: Brian Walshe Trial Date: What Really Happened with the Verdict

Instead of saving the Republic, the assassination of Julius Caesar triggered a series of civil wars that lasted for over a decade. It cleared the path for Caesar’s grand-nephew and adopted son, Octavian (later known as Augustus), to become the first true Emperor of Rome. By trying to kill a "king," the Senate accidentally created an Empire.

Why this still matters today

You can see the ripples of this event in almost every modern political structure. The "checks and balances" we talk about in modern democracy were heavily influenced by the failures of the Roman Senate to contain Caesar.

It’s a lesson in "the law of unintended consequences."

If you're looking to dive deeper into how this changed the world, start by looking at the primary sources. Don't just take a historian's word for it. Read the letters of Cicero from that time. Cicero wasn't in on the plot, but he hated Caesar and cheered when it happened. His letters give you a raw, real-time look at the panic that gripped Rome in the weeks following the Ides of March.

Next Steps for the History Enthusiast:

- Examine the Primary Sources: Check out Suetonius's The Twelve Caesars and Plutarch’s Parallel Lives. They disagree on details, which is exactly why they're worth reading—you get to see how history is constructed.

- Visit the Site (Virtually or In-Person): If you're ever in Rome, go to the Largo di Torre Argentina. It's a sunken square full of stray cats and temple ruins. It’s also the spot where the Theater of Pompey stood. That’s where it happened.

- Study the "First Autopsy": Look into the report by the physician Antistius. It’s a fascinating early example of forensic science being used for political record-keeping.

- Follow the Money: Look into the coinage minted by Brutus after the murder—specifically the "EID MAR" denarius, which features two daggers and a liberty cap. It’s one of the few times a murderer literally put the crime on a piece of currency.

The Republic died because it couldn't adapt to the power of a single popular individual. Whether you see Caesar as a tyrant or a reformer, his death proved that once the institutional "guardrails" are broken, a dagger isn't enough to fix the engine of state.