May 13, 1981, started out as a beautiful, sun-drenched Wednesday in Rome. It was the Feast of Our Lady of Fátima. Thousands of people had gathered in St. Peter’s Square for the weekly general audience. Pope John Paul II, the "People’s Pope," was doing what he loved—riding in his open-top Fiat Campagnola, reaching out to touch hands, and blessing children. Then, at 5:17 PM, the world changed. Four shots rang out. A 23-year-old Turkish gunman named Mehmet Ali Ağca stood in the crowd, a 9mm Browning Hi-Power pistol in his hand, and pulled the trigger. Two bullets hit the Pope. One grazed his elbow; the other tore through his abdomen.

It was chaos. Pure, unadulterated panic.

The Pope collapsed. His white cassock was suddenly soaked in red. It’s hard to imagine now, in our world of bulletproof glass and massive security perimeters, but back then, the Pope was incredibly vulnerable. He was basically a sitting duck in that open jeep. While the crowd tackled Ağca, the "Popemobile" sped away toward the Gemelli Hospital.

The Medical Miracle and the "Hand" of Mary

Honestly, John Paul II probably shouldn't have survived. One of the bullets missed his central aorta by a fraction of an inch. If that vessel had been severed, he would have bled out right there on the cobblestones before the ambulance even arrived. He underwent five hours of surgery. Surgeons worked frantically to repair the damage to his intestines.

The Pope himself later said something that still gives people chills. He credited his survival to the Virgin Mary, famously stating, "One hand pulled the trigger, and another guided the bullet." He believed the bullet’s strange, curved trajectory—which somehow avoided every vital organ despite passing through his body—was divine intervention. Whether you’re religious or not, the logistics of his survival were nothing short of a medical anomaly.

Who was Mehmet Ali Ağca?

The shooter wasn't some random lunatic. Not exactly. Mehmet Ali Ağca was a professional assassin with links to the Grey Wolves, a Turkish ultra-nationalist group. He had already escaped a Turkish prison after killing a journalist. So, how did he get to Rome? Why would a Turkish nationalist want to kill the head of the Catholic Church?

This is where things get messy and deep into Cold War territory.

💡 You might also like: 39 Carl St and Kevin Lau: What Actually Happened at the Cole Valley Property

For years, investigators chased the "Bulgarian Connection." The theory was that the Soviet Union’s KGB feared John Paul II because of his support for the Solidarity movement in his native Poland. They saw him as a direct threat to the stability of the Soviet bloc. The theory goes that the KGB hired the Bulgarian secret service, who then hired Ağca to do the dirty work.

Ağca didn't help clear things up. The guy was a total wild card. During his trial and subsequent years in prison, he changed his story more times than anyone could count. He claimed he was Jesus Christ. He claimed he was working for the Vatican. He claimed the Bulgarians were definitely behind it. Then he retracted it. Even today, historians like Paul Kengor and investigative journalists remain divided on whether the Kremlin officially ordered the hit.

The Meeting That Shook the World

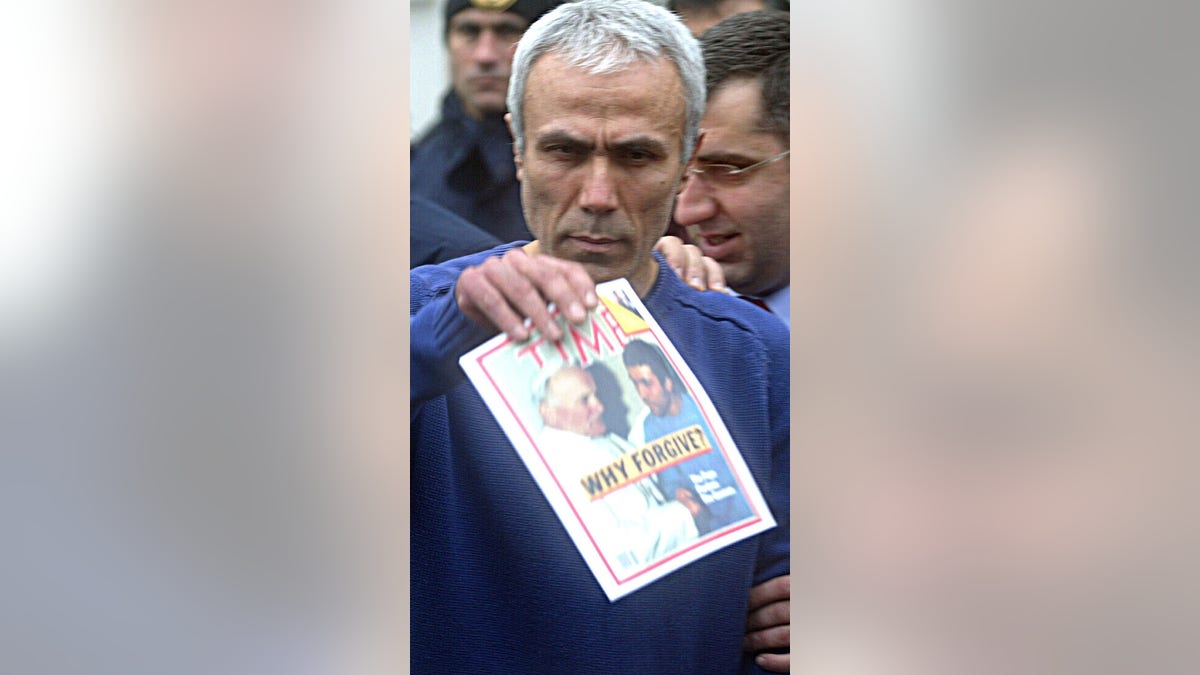

Perhaps the most famous part of the whole assassination attempt of Pope John Paul II isn't the shooting itself, but the forgiveness that followed. In 1983, John Paul II walked into Rebibbia Prison. He sat down in a small cell with the man who tried to kill him.

They talked for 20 minutes.

We don’t know exactly what was said—the Pope kept that private—but we know the outcome. He forgave Ağca. It wasn't just a PR stunt. It was a radical act of grace that fundamentally defined his papacy. Ağca, for his part, seemed less interested in forgiveness and more obsessed with how the Pope had survived. He couldn't understand how a professional hitman had missed from such close range. He was preoccupied with the "Third Secret of Fátima," convinced there was a supernatural force at play.

Security Failures and the Aftermath

Looking back, the security was basically non-existent. The Vatican didn't have the sophisticated intelligence-gathering tools they have now. They relied on "The Gendarmes" and the Swiss Guard, but their primary focus was crowd control, not counter-terrorism.

📖 Related: Effingham County Jail Bookings 72 Hours: What Really Happened

After 1981, everything changed.

- The "Popemobile" got an upgrade: bulletproof glass became the standard.

- The Vatican intensified its cooperation with international intelligence agencies like the CIA and Italy’s DIGOS.

- General audiences became more structured, with stricter screening processes for those entering the square.

People often forget that two other people were injured that day. Ann Odre and Rose Hall, two pilgrims, were struck by the stray bullets. Their stories are usually buried in the footnotes, but they represent the collateral damage of a moment that could have sparked a global geopolitical crisis. If the Pope had died, Poland might have erupted in a way that would have forced a Soviet invasion years before the Wall actually fell. The stakes were that high.

Moving Beyond the Conspiracy Theories

It's easy to get lost in the "Who done it?" of it all. Was it the KGB? Was it the Stasi? Was it a lone wolf?

While the Mitrokhin Commission in Italy later concluded that the Soviet Union was indeed behind the plot, the evidence remains circumstantial in many eyes. There’s no "smoking gun" memo from Moscow. What we do have is the legacy of a man who survived a near-fatal wound and used it to cement his role as a global moral authority.

The bullet that hit the Pope didn't end up in a trash can or a police evidence locker forever. In a move that brings the whole story full circle, John Paul II gave the bullet to the Shrine of Our Lady of Fátima in Portugal. It was placed inside the crown of the statue of the Virgin Mary. If you go there today, you can see it. It fits perfectly into a hole that had been left in the crown's design decades before the shooting ever happened. Weird coincidence? Maybe.

Why It Still Matters in 2026

The assassination attempt of Pope John Paul II remains a case study in how a single event can shift the course of history. It reminds us of the fragility of peace during the Cold War. It shows us how religious symbols can become political targets. But mostly, it’s a story about the weird, often inexplicable ways that history unfolds.

👉 See also: Joseph Stalin Political Party: What Most People Get Wrong

If you're looking to understand this event deeply, don't just watch the graining footage of the Fiat driving through the crowd. Look at the geopolitical maps of 1981. Look at the rise of the Solidarity movement in Gdansk. The shooting wasn't just a crime; it was a desperate attempt to stop a tidal wave of change that was already sweeping across Eastern Europe.

How to Explore This History Today

If you find yourself in Rome or interested in the Cold War era, there are a few things you should actually do to get the full picture:

Visit the Gemelli Hospital

There is a statue of the Pope there, and the "Pope's Room" on the 10th floor has been preserved. It’s a sobering reminder of his long recovery and the multiple times he returned there for health issues stemming from the shooting.

Examine the Vatican Secret Archives (Digitally)

While you can’t just walk in, many documents related to the era have been declassified. Look for research by historians who specialize in "Ostpolitik"—the Vatican's 20th-century diplomacy with the Soviet Union.

Read the Mitrokhin Archive

This is the most comprehensive look at KGB operations. It provides the most convincing, though still debated, evidence regarding the Eastern Bloc's involvement in the plot.

Analyze the "Third Secret of Fátima"

The Vatican officially released the text of the secret in 2000. It describes a "Bishop dressed in White" falling to the ground under a hail of gunfire. Reading the text alongside the events of 1981 offers a fascinating look at how the Church interprets its own history through the lens of prophecy.

The event didn't just change the Vatican; it changed how we protect public figures and how we perceive the intersection of faith and global politics. It was the day the "People's Pope" became a martyr who lived, and that fact alone changed the 20th century forever.