Think about a basketball. Or the Earth. Or even a tiny marble sitting on your desk. They all have one thing in common: they’re round. But if you actually try to measure the "flat" surface of that roundness—the area for a sphere—things get weird fast.

You can't just lay a ruler across a curve. It doesn't work that way.

Honestly, most of us haven't thought about this since tenth-grade geometry, but the surface area of a sphere is actually one of the most elegant pieces of math ever discovered. It’s not just a random string of variables. It's a relationship between a circle and the space it occupies.

The Formula You Probably Forgot

Let's just get the "math-y" part out of the way first. If you're looking for the area for a sphere, you need this:

🔗 Read more: Is There a Pumpkin Emoji? Why the Jack-O-Lantern Rules Your Keyboard

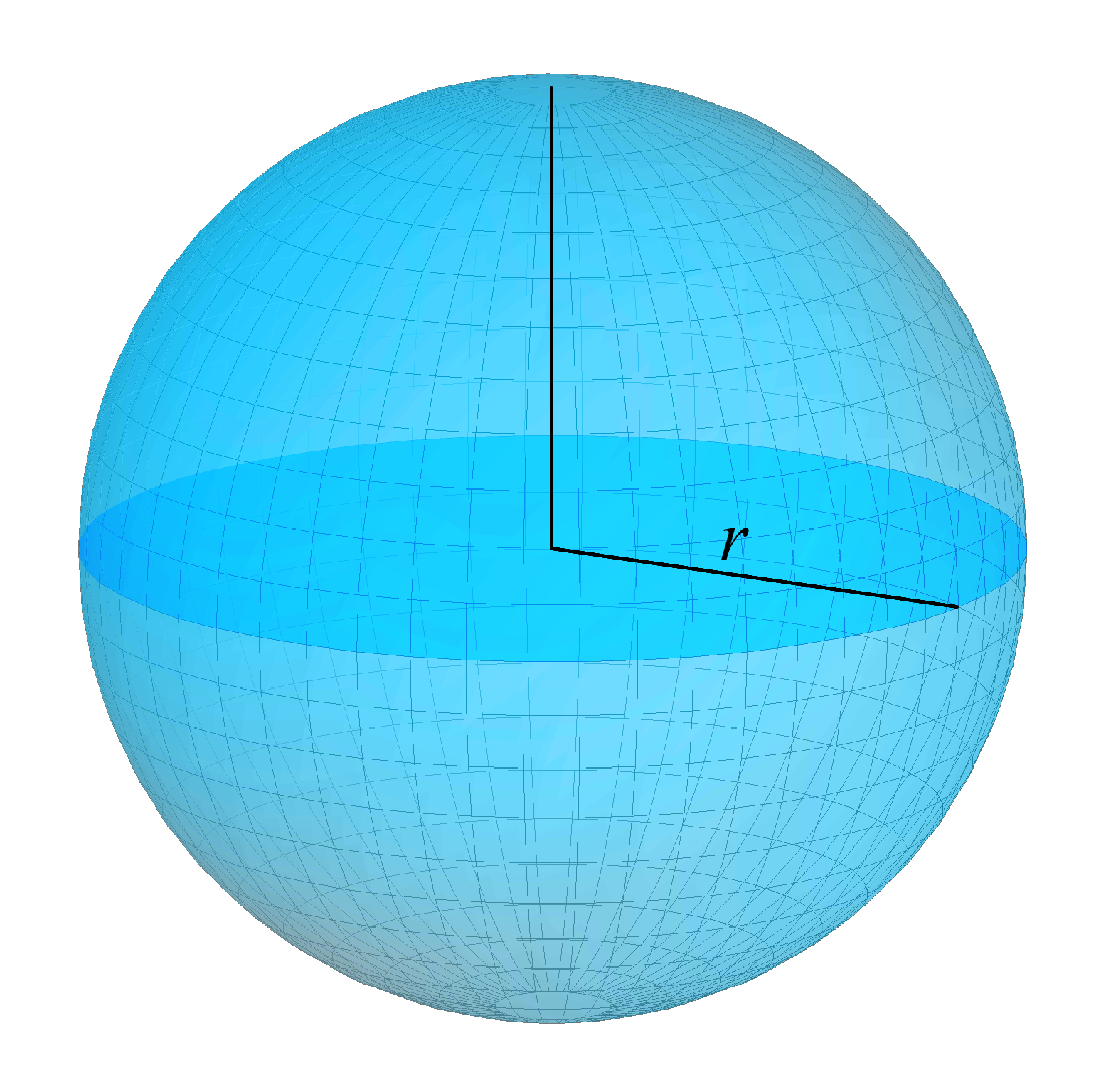

$$A = 4\pi r^2$$

That's it. It looks simple, right? But stop and actually look at it for a second. You’ve got the $r^2$, which is basically the area of a flat square. Then you have $\pi$. And then that random number 4.

Why 4?

It’s one of those things that feels like it should be more complicated, like maybe it should involve some crazy calculus or a three-dimensional constant we haven't heard of. But Archimedes—the guy who supposedly shouted "Eureka!" in his bathtub—figured this out over 2,000 years ago. He realized that the surface area of a sphere is exactly the same as the lateral surface area of a cylinder that fits perfectly around it.

He was so obsessed with this discovery that he actually wanted it carved onto his tombstone. Talk about a math nerd.

Visualizing the Area for a Sphere Without Going Insane

Most people struggle with this because you can't "unroll" a sphere.

If you take a soda can (a cylinder), you can peel the label off and lay it flat on a table. It becomes a rectangle. Easy. If you try to do that with a sphere—say, by peeling an orange—you end up with a mess of jagged, torn pieces. You can't make a sphere flat without stretching or tearing it. This is why every map of the world you've ever seen is technically a lie; you can't represent the area for a sphere on a flat piece of paper without distorting the sizes of the continents.

Here’s a better way to wrap your head around it. Imagine you have a circle with the same radius as your sphere. The area of that flat circle is $\pi r^2$.

Now, imagine taking four of those circles. If you could somehow stretch and mold those four circles perfectly over the surface of the ball, they would cover it exactly. No gaps. No overlaps.

Four circles. One sphere.

It’s a perfect 4-to-1 ratio.

Real-World Stakes: It’s Not Just for Textbooks

You might think, "When am I ever going to need to calculate the area for a sphere in real life?"

Unless you're an engineer or a physicist, maybe never. But the world depends on it. Take NASA, for example. When they design a heat shield for a capsule returning from the International Space Station, they aren't just guessing. They need to know the exact surface area that will be hitting the atmosphere. If they're off by a tiny fraction, the heat distribution is wrong, and well, things get bad.

✨ Don't miss: Why Black No Dock Wallpaper Is the Only Way to Clean Up Your iPhone Home Screen

Or think about the paint industry. If you’re painting a giant spherical storage tank for natural gas, you don't just "eyeball" how many gallons you need. Paint is expensive. You use the surface area formula to calculate the exact coverage.

In biology, it’s even cooler. Cells are often spherical because that shape provides the smallest surface area for a given volume. It’s all about efficiency. The sphere is nature's way of being stingy with space.

Why the Radius Changes Everything

In the formula $4\pi r^2$, the $r$ is squared. This is the part that catches people off guard.

If you double the size (the radius) of a ball, you don't just double the surface area. You quadruple it.

- Take a small balloon with a radius of 1 inch. The area is roughly 12.5 square inches.

- Blow it up until the radius is 2 inches.

- The area isn't 25. It’s 50.2.

This exponential growth is why stars—which are mostly spheres—emit such massive amounts of energy. A small increase in a star's size leads to a gargantuan increase in the surface area available to radiate light and heat into the universe.

Common Mistakes People Make

Most errors come from mixing up the diameter and the radius. It’s a classic trap. If someone tells you they have a 10-inch ball, that 10 inches is usually the diameter. But the formula needs the radius.

If you plug 10 into the formula instead of 5, your answer will be four times larger than it should be. You'll end up buying way too much paint or overestimating the heat loss of a planet.

Another one? Confusing area with volume.

- Surface Area ($4\pi r^2$) is the skin. It's 2D. It’s measured in square units ($in^2$, $cm^2$).

- Volume ($\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3$) is the guts. It's 3D. It’s measured in cubic units ($in^3$, $cm^3$).

Think of it like a chocolate-covered cherry. The area for a sphere tells you how much chocolate you need for the shell. The volume tells you how much cherry filling is inside.

The Calculus Perspective (For the Brave)

If you really want to understand where this comes from, you have to look at integration.

Basically, you can think of a sphere as a bunch of infinitely thin circles stacked on top of each other, or as a sum of tiny little squares across a curved surface. By using calculus, we can prove that $4\pi r^2$ isn't just a lucky guess—it’s the mathematical derivative of the volume of a sphere.

$V = \frac{4}{3}\pi r^3$

If you take the derivative of that with respect to $r$:

$\frac{dV}{dr} = 4\pi r^2$

Boom. Surface area.

This connection between the "inside" and the "outside" of a sphere is one of the most satisfying "aha!" moments in mathematics. It shows that the structure of the universe isn't random. It’s deeply interconnected.

Actionable Steps for Measuring Your Own Sphere

If you actually have a physical object in front of you and you need to find its area, don't try to measure the radius through the center of the ball with a ruler. You’ll never find the exact center.

Instead, do this:

- Get a string. Wrap it around the widest part of the sphere (the equator). This gives you the circumference ($C$).

- Find the radius. Divide that circumference by $2\pi$ (about 6.28). Now you have $r$.

- Plug it in. Square that radius, multiply by $\pi$ (3.14159), and then multiply by 4.

- Double check. If your answer seems way too small, you probably forgot to square the radius. If it seems way too big, you probably used the diameter.

Using a soft measuring tape—the kind tailors use—makes this a lot easier than using a stiff metal one.

Understanding the area for a sphere gives you a weird kind of superpower. You start seeing the world differently. You realize why bubbles are always round (surface tension minimizing area) and why planets aren't cubes. It’s all about that 4-to-1 ratio, a constant that has existed since the Big Bang, just waiting for someone like Archimedes to notice it.