History is messy. If you grew up in the American school system, you probably learned a very "sanitized" version of the anti slavery movement in the united states. It usually goes like this: some Quakers got upset, Harriet Tubman ran the Underground Railroad, Frederick Douglass wrote a book, and then Abraham Lincoln signed a paper that fixed everything.

That's not how it happened. Not even close.

The real story is way more violent, politically chaotic, and honestly, a lot more inspiring because the people involved were flawed humans taking massive risks. It wasn't just a "movement." It was a centuries-long, multi-front war involving guerrilla tactics, legal battles that went nowhere, and a massive shift in how the average person viewed morality.

It Started Way Earlier Than You Think

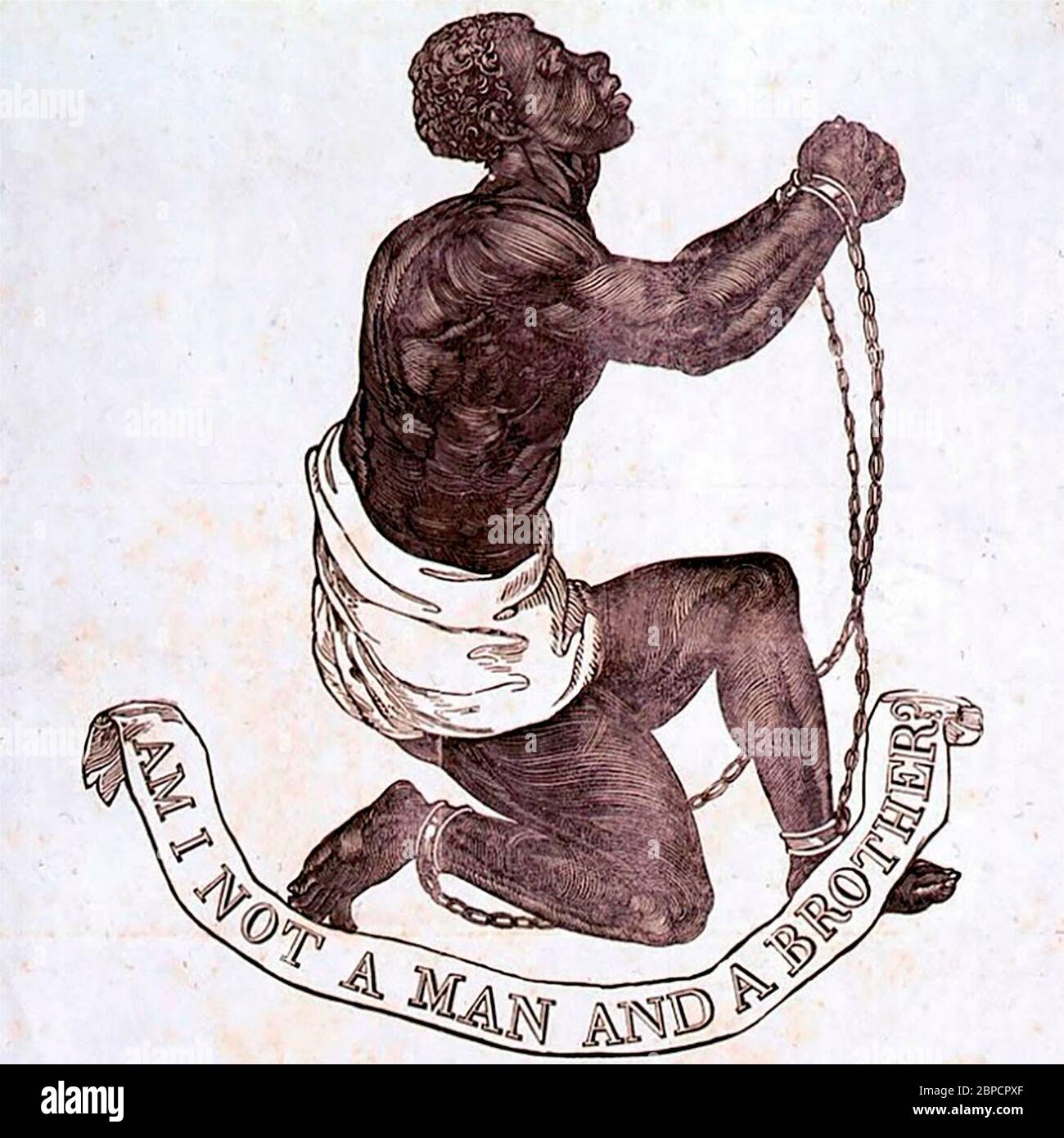

People often pin the start of the anti slavery movement in the united states to the 1830s with the rise of "radical" abolitionists. But resistance was there from the first day an enslaved person stepped off a ship. Early on, it was mostly religious groups like the Mennonites and Quakers in Pennsylvania. In 1688—long before the Revolution—a group of Germantown Quakers signed a protest against "the traffic of men-body."

They weren't popular.

Even among other Quakers, these early protesters were seen as troublemakers. It took nearly a century for the Society of Friends to actually ban slaveholding among its members.

Then came the American Revolution. The irony was thick. You had guys like Thomas Jefferson writing about "unalienable rights" while holding hundreds of people in bondage. This hypocrisy didn't go unnoticed. Black pioneers like Lemuel Haynes used the Revolution’s own logic to argue for freedom. During this era, Northern states started passing gradual emancipation laws. Pennsylvania’s 1780 law was a weird compromise; it didn't free people instantly but basically said, "If you're born after this date, you'll be free... eventually, after you work for 28 years."

It was a slow, agonizing process.

💡 You might also like: Percentage of Women That Voted for Trump: What Really Happened

The Shift From "Slow and Steady" to "Right Now"

By the 1830s, the vibe changed. People were tired of waiting. This is where the anti slavery movement in the united states got radical. Enter William Lloyd Garrison.

He started a newspaper called The Liberator in 1831. Garrison was intense. He didn't want gradual change. He wanted "immediatism." He famously burned a copy of the Constitution, calling it a "covenant with death" because it protected slavery. Garrison was so hated in the North—not just the South—that a mob in Boston once put a rope around his neck and dragged him through the streets.

It’s easy to forget that being an abolitionist in a Northern city like New York or Cincinnati was dangerous. Northern business owners made a killing off Southern cotton. They didn't want the boat rocked.

The Black Intellectual Powerhouse

While Garrison was the loud voice in the press, the real backbone of the anti slavery movement in the united states was the network of free Black activists. Frederick Douglass is the name everyone knows, and for good reason. His 1845 narrative blew the doors off the "happy slave" myth that Southerners tried to sell to the world.

But there were others you should know:

- James McCune Smith: The first African American to hold a medical degree. He used science to debunk the racist "biology" of the time.

- Frances Ellen Watkins Harper: A brilliant poet and speaker who refused to give up her seat on a segregated trolley in Philadelphia—decades before Rosa Parks.

- The Tappan Brothers: Wealthy white businessmen who poured their fortunes into the movement, even when their warehouses were being burned down by pro-slavery mobs.

The Underground Railroad Wasn't a Tunnel

One of the biggest misconceptions about the anti slavery movement in the united states is that the Underground Railroad was a series of literal tunnels. It wasn't. It was a "secret" that everyone kind of knew about but couldn't prove. It was a decentralized network of "stations" (homes, barns, churches) and "conductors" (guides).

Harriet Tubman is the icon here, and honestly, she deserves even more credit than she gets. She didn't just lead people to freedom; she was a master of psychological warfare. She carried a pistol. She told people that if they tried to turn back, she'd shoot them, because one defector could compromise the whole line. She never lost a "passenger."

📖 Related: What Category Was Harvey? The Surprising Truth Behind the Number

But the Railroad also moved West. Many people escaped to Mexico, where slavery had been abolished in 1829. Others fled into the Florida Everglades to live with the Seminole tribes. It was a global escape map.

The Political Explosion: 1850 and Beyond

Things got real in 1850. The Fugitive Slave Act was passed. This law basically turned every Northerner into a slave catcher. If you saw someone you suspected was a runaway and didn't help capture them, you could be fined or jailed.

This backfired spectacularly for the South.

Moderate Northerners who didn't really care about slavery suddenly found themselves forced to participate in it. They saw Black neighbors being snatched off the street in broad daylight. This turned the anti slavery movement in the united states from a niche moral cause into a mass political movement.

It led to the "Christiana Riot" in Pennsylvania, where a group of Black men and women fought back against a slave owner and federal marshals, successfully defending their freedom. It led to the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe. People today mock the book for its stereotypes, but in 1852, it was a nuclear bomb. It became the best-selling novel of the 19th century and made the horrors of slavery a dinner-table conversation.

Violence Was Inevitable

There’s a myth that the Civil War was a tragic misunderstanding. It wasn't. It was a deliberate escalation.

By the late 1850s, the anti slavery movement in the united states had split. Some, like Douglass, still believed in using the political system. Others followed John Brown.

👉 See also: When Does Joe Biden's Term End: What Actually Happened

Brown was a different breed. He believed that talk was cheap and "without the shedding of blood, there is no remission of sins." In 1859, he and a small group of Black and white men raided the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. They wanted to start a massive slave revolt.

They failed. Brown was hanged.

But as he walked to the gallows, he handed a note to a guard stating that the "crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away; but with Blood." He was right. A year later, the country was at war.

What Actually Happened After the War?

The 13th Amendment officially ended slavery in 1865. But the anti slavery movement in the united states didn't just pack up and go home. They knew the work wasn't done. The movement morphed into the fight for Reconstruction, the 14th Amendment (citizenship), and the 15th Amendment (voting rights).

The tragedy is that much of this progress was rolled back by Jim Crow laws and the "Lost Cause" myth, which tried to rewrite the war as being about "states' rights" instead of slavery. It took another century for the Civil Rights Movement to pick up the tools the abolitionists had forged.

Actionable Insights for Today

Understanding the anti slavery movement in the united states isn't just a history lesson. It offers a blueprint for how social change actually happens. It’s never a straight line.

If you want to dive deeper, here is how you can actually engage with this history:

- Visit the Real Sites: Skip the "plantation tours" that focus on the wallpaper. Go to the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati or the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park in Maryland.

- Read the Primary Sources: Don't just read about Frederick Douglass. Read his "What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?" speech. It’s arguably the most powerful piece of oratory in American history.

- Support Modern Abolition: The 13th Amendment has a "loophole" for prison labor. Organizations like the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) work on these legacy issues today.

- Trace the Local History: Most people don't realize that abolitionist "safe houses" are probably in their own town. Check your local historical society records for "vigilance committees."

The movement proved that a small group of dedicated people—often dismissed as "extremists" or "troublemakers"—can eventually shift the entire moral compass of a nation. It took too long. It cost too much. But it changed everything.