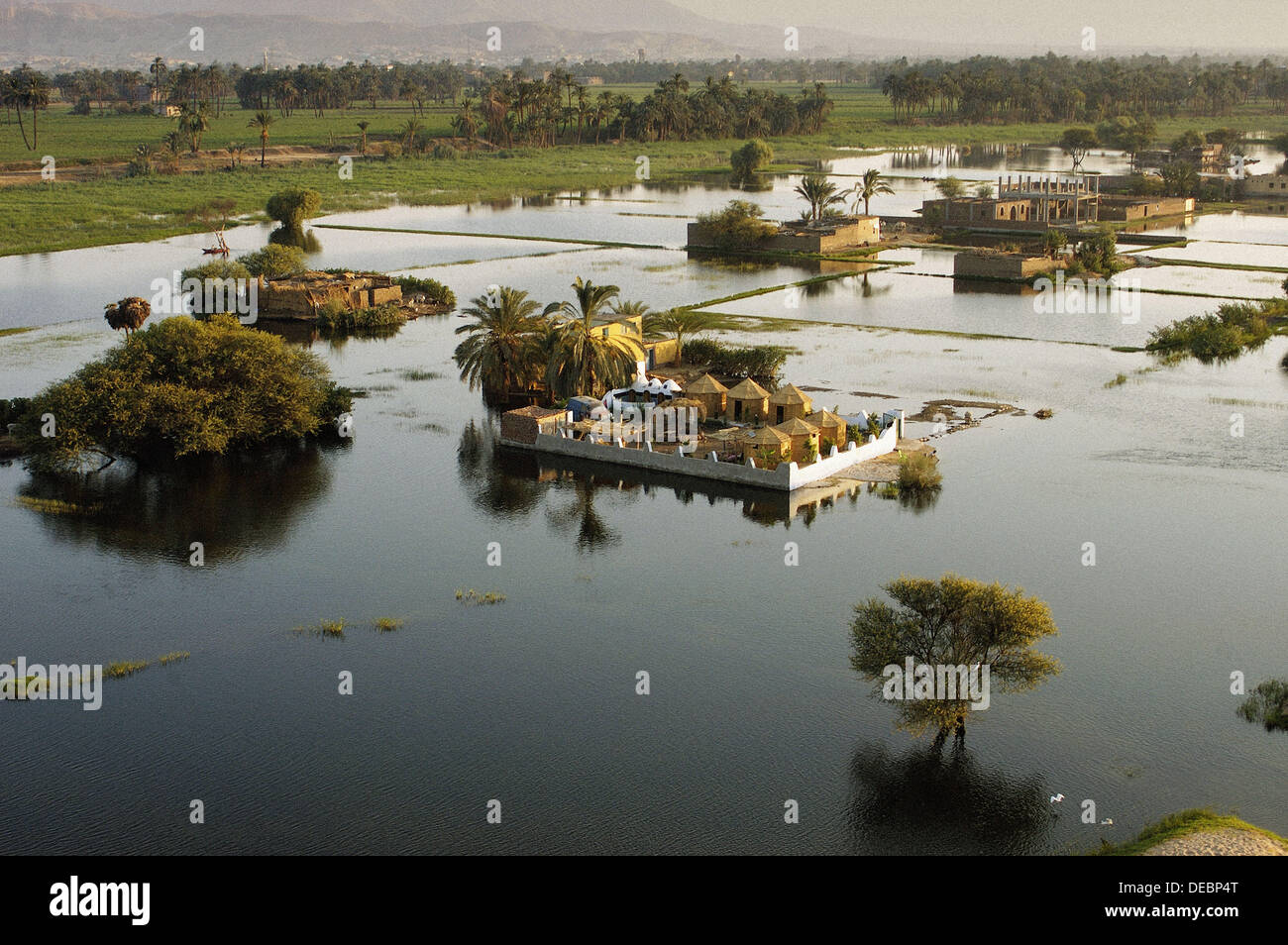

It’s hard to wrap your head around just how much the annual flooding of the Nile river dictated every single breath of human life in Northeast Africa for basically five thousand years. Imagine a world where your entire calendar, your tax bracket, and whether or not your kids ate dinner depended on a single weather event happening hundreds of miles away in the Ethiopian Highlands. It wasn’t just a "seasonal event." It was everything.

If the water rose too high? Your mud-brick house dissolved. Too low? Everyone starved.

Modern tourists visiting the pyramids or taking a luxury cruise between Luxor and Aswan often miss the reality that the Nile they see today is essentially a "tamed" version of its former self. Since the completion of the High Dam in 1970, that rhythmic, muddy pulse has been flatlined. But to understand why Egypt is even a country, you have to understand the chaos and the genius of the Akhet.

What Actually Caused the Annual Flooding of the Nile River?

For a long time, people had no clue why the river rose. The ancient Greeks were baffled. Herodotus spent ages trying to figure out why the Nile behaved differently than any other river he knew. Most rivers flood in the spring when snow melts. The Nile? It surged in the heat of the summer.

The secret lay in the monsoons.

The Nile is fed by two main tributaries: the White Nile and the Blue Nile. While the White Nile provides a steady flow from Lake Victoria, it’s the Blue Nile that brought the "boom." Every summer, heavy monsoon rains would hammer the Ethiopian Plateau. That water would rush down into the valley, carrying millions of tons of volcanic silt.

This wasn't just water. It was fertilizer.

By the time the surge hit Cairo in August, the river was thick and reddish-black. The locals called it Hapi. They didn't just see it as H2O; they saw it as a god bringing a gift. This "gift" was the kemet, the rich black soil that gave Egypt its ancient name. Without that specific silt, the Sahara Desert would have swallowed the entire civilization before the first stone of a pyramid was ever laid.

The Nilometer: How Ancient Bureaucrats Predicted the Future

Ancient Egyptians were surprisingly nerdy about data. Since the annual flooding of the Nile river determined the harvest, the government needed to know exactly how much to tax people before the crops even grew.

They built things called Nilometers.

📖 Related: London to Canterbury Train: What Most People Get Wrong About the Trip

You can still see them today on Elephantine Island in Aswan or on Rhoda Island in Cairo. These weren't high-tech gadgets; they were stone staircases or conduits leading down into the river with markings on the walls.

- 16 cubits: This was the "sweet spot." It meant the water would reach the outer fields without washing away the villages. Prosperity.

- 12-13 cubits: Hunger was coming. The water wouldn't reach the high ground.

- 20 cubits: Disaster. The water would breach the dikes and destroy infrastructure.

It’s wild to think that a priest standing on a staircase in Aswan could basically predict the economic GDP of the entire kingdom for the next twelve months. If the markings showed a "low Nile," the Pharaoh's tax collectors knew they’d have a riot on their hands if they asked for too much grain.

The Science of Silt and Why It Matters Now

People talk about "the flood" like it was just a big puddle. It was a geological engine.

The Blue Nile brought down minerals like iron and potassium. When the water sat on the fields during the Akhet season (June to September), these minerals settled. Farmers didn't need to rotate crops or use chemical fertilizers. The river did the maintenance for them.

Then everything changed.

When the Aswan High Dam was finished in 1970, the annual flooding of the Nile river stopped. Period. The water is now managed by engineers at a control center. Lake Nasser holds the floodwaters back, releasing them gradually throughout the year to generate electricity and ensure year-round irrigation.

But there’s a massive catch.

Since the flood no longer happens, that rich Ethiopian silt never makes it to the delta. It just piles up at the bottom of Lake Nasser. Now, Egyptian farmers have to spend billions on artificial fertilizers. The Nile Delta, which used to grow outward into the Mediterranean, is actually shrinking and eroding because there's no new silt to rebuild the coastline. It's a classic case of solving one problem (famine and power) while accidentally creating a dozen ecological ones.

Living With the Flood: The "Basin Irrigation" System

Before the dams, Egyptians used a system called basin irrigation.

👉 See also: Things to do in Hanover PA: Why This Snack Capital is More Than Just Pretzels

They didn't just let the water run wild. They built a massive network of earthen walls that divided the valley into "basins." When the Nile flooded, they’d open a gap in the wall, let the muddy water fill a basin, and then close it. The water would sit there for about 40 to 60 days.

During this time, the silt settled. The ground got a deep soak.

Once the river started to recede, the farmers would drain the remaining water back into the Nile and immediately throw seeds into the mud. They didn't even have to plow most of the time. They just let pigs or sheep walk over the seeds to stomp them into the muck.

It was arguably the most sustainable farming system in human history. It lasted for 5,000 years without depleting the soil. Compare that to modern industrial farming which can ruin a field in fifty years.

Myths vs. Reality: Did They Really Sacrifice Virgins?

You’ve probably heard the story about Egyptians throwing a beautiful girl into the river to please the Nile god.

Honestly? It's almost certainly a myth.

While there are Arabic chronicles from centuries later that mention a "Bride of the Nile" (Arous El Nil) ceremony, most Egyptologists like Dr. Zahi Hawass or the late Barry Kemp have noted there is zero archaeological evidence that the Pharaohs were chucking people into the water. Instead, they’d throw in wooden dolls, flowers, or food.

The "sacrifice" was usually a festival. It was a party. They called it the Wafaa el-Nil. Even today, there’s a vestige of this in Egyptian culture—a celebration that the river has "fulfilled its promise."

Why the Flood Still Matters in a Post-Dam World

Even though the water doesn't physically spill over the banks anymore, the geopolitics of the annual flooding of the Nile river are more tense than ever.

✨ Don't miss: Hotels Near University of Texas Arlington: What Most People Get Wrong

In 2026, the big "elephant in the room" is the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD).

Ethiopia wants to harness that same monsoon energy that fueled the Pharaohs to provide electricity for 60 million people. Egypt, which is 97% desert and depends on the Nile for almost all its water, is understandably terrified. If Ethiopia holds back too much water to fill their reservoir during a drought year, the "virtual flood" that Egypt relies on could disappear.

It’s the same old story, just with concrete and turbines instead of Nilometers and papyrus.

How to Experience the "Legacy" of the Flood Today

If you’re traveling to Egypt to see the impact of the Nile, don't just stay in Cairo. Cairo is a concrete jungle where the river is fenced in by corniche walls and casinos.

- Visit the Nilometer on Rhoda Island: It’s one of the oldest Islamic-era structures in Cairo (built around 861 AD). You can climb down the spiral stairs and see exactly where the water used to hit. It’s eerie and cool.

- Take a Felucca in Aswan: This is where the Nile is at its most "natural." Because of the granite cataracts (boulders in the river), the water has to squeeze through narrow channels. You get a sense of the power the river had before it was dammed.

- Explore the West Bank of Luxor: Walk through the green fields that sit right on the edge of the desert. You can literally stand with one foot in lush clover and one foot in scorching sand. That sharp line is exactly where the annual flooding of the Nile river used to stop.

Moving Forward: The Future of the River

The Nile is currently at a crossroads. Climate change is making the monsoon rains in Ethiopia more unpredictable—sometimes they're massive, causing floods in Sudan, and sometimes they fail completely.

If you're interested in the sustainability of the region, keep an eye on desalination projects in Alexandria and water recycling initiatives in the Delta. Egypt can no longer rely on a "gift" from the gods. They have to manage every drop.

The "flood" may be a thing of the past, but the river's rhythm still dictates the future of 100 million people. Understanding that history isn't just about looking at old temples; it's about understanding how humans adapt when their environment completely changes the rules of the game.

Next Steps for Deep Diving:

- Check out the UNESCO reports on the Nile Delta erosion to see the environmental impact of the loss of silt.

- If you're in Cairo, spend an afternoon at the Museum of Irrigation—it sounds dry (pun intended), but it’s actually a fascinating look at how 19th-century engineers tried to "fix" the river.

- Look into the current GERD negotiations between Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia to understand why water rights are the biggest security issue in Africa today.