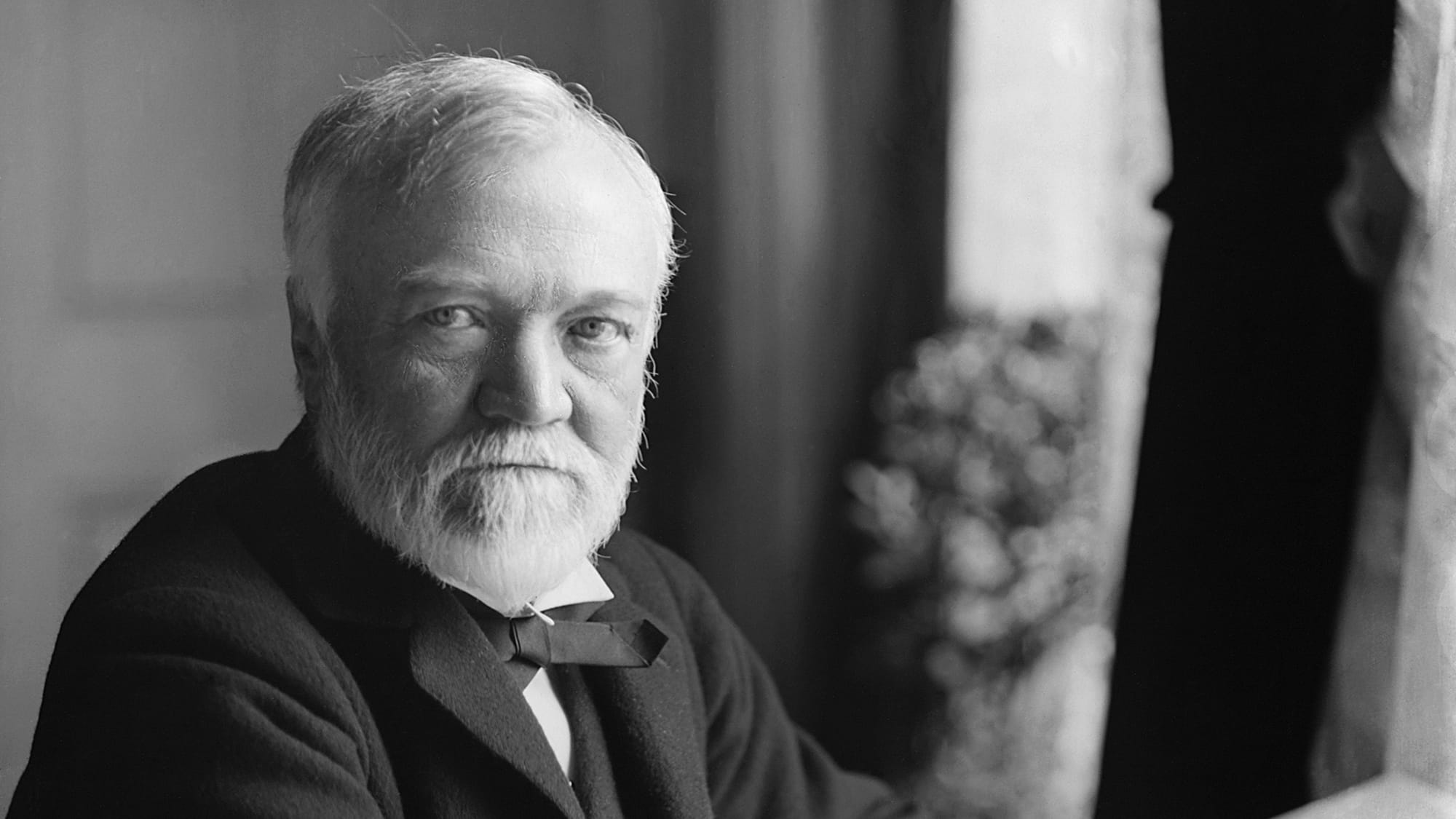

Andrew Carnegie was kind of a walking contradiction. He was the richest man in the world, a steel tycoon who built an empire on the backs of workers earning pennies, yet he spent his sunset years trying to give every single cent away.

In 1889, he sat down and wrote an essay originally titled just "Wealth" for the North American Review. Most people know it as the Andrew Carnegie Gospel of Wealth. It wasn't just a suggestion for the rich to be "nice." It was a radical, borderline aggressive manifesto that claimed the wealthy are basically just "trustees" for the public.

He didn't think the rich owned their money. Honestly, he thought they were just temporary managers of it.

What the Andrew Carnegie Gospel of Wealth Actually Said

Carnegie didn't mince words. He believed that the "law of competition" was inevitable and good because it produced high-quality goods at low prices. But he knew it created a massive gap between the rich and the poor. To him, the solution wasn't communism or government handouts.

It was the "proper administration" of wealth by the people who were smart enough to earn it in the first place.

He laid out three ways to handle a fortune:

💡 You might also like: Wegmans Meat Seafood Theft: Why Ribeyes and Lobster Are Disappearing

- Leaving it to your family: He hated this. He thought it usually ruined the kids and made them "unworthy."

- Leaving it for public use after death: He was skeptical here too. He figured people only did this because they couldn't take it with them. Plus, he worried the money would be mismanaged once the owner was gone.

- Giving it away while you’re alive: This was his gold standard. He believed the rich should live modestly, provide moderately for their families, and then treat the rest as a "trust fund" for the community.

"The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced." That’s his most famous line. It wasn't a suggestion; it was a threat of social shame.

The Dark Side of the "Gospel"

We can't talk about Carnegie's generosity without talking about how he got the money. It’s messy. While he was writing about the "ties of brotherhood" between rich and poor, his company was involved in the Homestead Strike of 1892.

His manager, Henry Clay Frick, locked out workers and hired Pinkerton detectives to break the strike. People died.

Carnegie was in Scotland at the time, but he didn't stop it. This creates a huge tension in the Andrew Carnegie Gospel of Wealth. Critics today—and even back then—pointed out that if he had just paid his workers better, maybe they wouldn't have needed his libraries so badly.

He was also a big believer in Social Darwinism. He genuinely thought the rich were "fitter" and therefore better equipped to decide how money should be spent than the poor themselves. It was incredibly paternalistic. He didn't want to give "alms" (handouts) because he thought that encouraged "the slothful."

📖 Related: Modern Office Furniture Design: What Most People Get Wrong About Productivity

Why He Loved Libraries (And Hated Cash Handouts)

If you’ve ever seen a "Carnegie Library" in your town, you’ve seen the Gospel in action. He funded over 2,500 of them. But there was a catch. He wouldn't just give a town a library for free.

The town had to:

- Provide the land.

- Pledge to use tax dollars to maintain it.

- Commit to buying the books.

He wanted "skin in the game." He wanted to provide the "ladders upon which the aspiring can rise," but he wouldn't carry them up the ladder himself.

The Estate Tax Twist

Here is something that surprises people: Carnegie was a huge fan of the inheritance tax.

He argued that the government should take a massive cut—nearly 100% in some of his writings—of large estates at death. Why? To force the rich to spend their money on society while they were still alive. He wanted to make it impossible to hoard wealth across generations.

👉 See also: US Stock Futures Now: Why the Market is Ignoring the Noise

Is the Gospel Still Alive?

You can see Carnegie's fingerprints all over modern billionaires. When Bill Gates and Warren Buffett started The Giving Pledge in 2010, they were essentially reviving the Andrew Carnegie Gospel of Wealth for the 21st century.

However, the conversation has shifted. In the 1880s, people were amazed a rich person wanted to give back. In 2026, we’re more likely to ask if that wealth should have been concentrated in one person’s hands to begin with.

Putting the Gospel into Practice

You don't need a billion dollars to take something away from Carnegie’s philosophy. The core idea is about stewardship rather than ownership.

- Audit your "surplus": Carnegie defined anything beyond "modest" living as trust funds. Define what "enough" looks like for you.

- Invest in "Ladders": Instead of just giving money, look for ways to give people tools. This could be mentorship, paying for a certification, or donating to a local community center.

- Give while you're here: Don't wait for a will to make an impact. The "disgrace" Carnegie feared was the missed opportunity to see your resources do good while you’re still around to guide them.

Whether you see him as a saintly philanthropist or a "robber baron" trying to buy a clean conscience, Carnegie’s essay forced the world to ask a question we still haven't answered: what does a person owe the society that made them rich?

Actionable Next Steps

- Read the Original Text: Find the 1889 essay "Wealth" online. It's surprisingly short and the prose is incredibly sharp.

- Evaluate Your Philanthropy: Look at your giving through Carnegie's lens. Are you giving "alms" that offer temporary relief, or are you investing in "ladders" that provide long-term growth?

- Check Your Local Library: Many Carnegie libraries are still standing. Visit one to see the physical legacy of this philosophy in your own backyard.