You probably don’t think about your chest until you’re winded from a flight of stairs or you feel that weird, fluttering thump of a heart skip. It’s just there. A cage of bone, some muscle, and the constant, rhythmic inflation of lungs. But honestly, the anatomy of the human chest is a mechanical masterpiece that would make any high-end engineer weep with envy. It’s a pressurized vacuum chamber, a protective fortress, and a pump house all rolled into one. If it fails for even a few seconds, the whole system collapses.

Most people call it the "chest," but if you're talking to a doctor or a kinesiologist, they’ll call it the thorax. This space—the thoracic cavity—runs from the base of your neck down to the diaphragm. It’s basically everything between your collarbones and the bottom of your ribs. It’s packed tight. There isn’t wasted space in there. Every millimeter is occupied by something vital, from the massive pipes of the aorta to the tiny, flickering nerves that keep your heart beating without you ever having to ask it to.

The Ribcage Isn’t Just a Dead Box

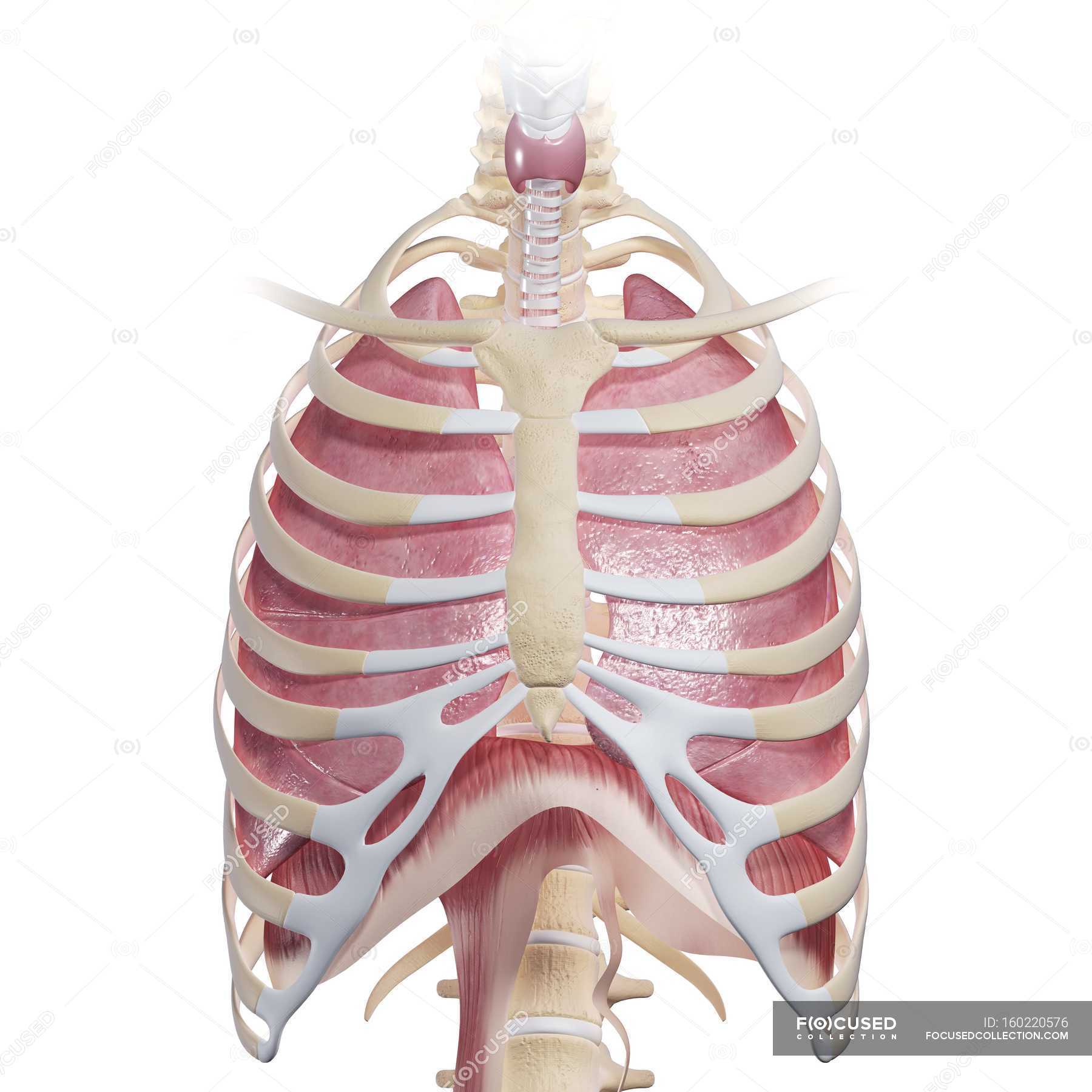

We tend to think of the ribs as a static cage, like the bars of a jail cell. That’s wrong. If your ribs were stiff, you’d suffocate. The anatomy of the human chest relies on a very specific kind of flexibility. You have 12 pairs of ribs, and they’re all doing something slightly different.

The first seven pairs are "true" ribs. They hook directly into the sternum—that flat bone in the middle of your chest—via costal cartilage. Then you’ve got the "false" ribs (8, 9, and 10), which connect to the cartilage of the rib above them rather than the sternum itself. And finally, the two floating ribs at the bottom. They just sort of hang there in the muscle of the abdominal wall. Why the variety? Because your chest needs to expand. When you inhale, your ribs move like a bucket handle lifting up. This increases the volume of the cavity, creates a vacuum, and sucks air into the lungs. If that cartilage turns to bone (which can happen with age or certain conditions), breathing becomes an agonizing chore.

The sternum itself is actually three separate parts: the manubrium at the top, the body in the middle, and the xiphoid process at the very bottom. That little pointy bit at the end? That’s the xiphoid. It’s mostly cartilage when you’re a kid, but it ossifies into bone as you get older. Fun fact: if you’re doing CPR and you hear a crack, it’s often this little guy or the ribs giving way under the pressure. It’s a brutal reality of emergency medicine, but it beats the alternative.

Muscles That Move the World (Or Just Your Air)

Muscle makes the movement happen. Everyone knows the "pecs"—the pectoralis major. These are the vanity muscles. They’re great for pushing doors open or looking good at the beach, but they aren't the primary drivers of the anatomy of the human chest in terms of survival.

The real workhorses are the intercostals. These are the thin layers of muscle tucked right between your ribs. You have internal ones and external ones. The externals help you breathe in; the internals help you force air out when you’re blowing out a candle or coughing.

📖 Related: The Human Heart: Why We Get So Much Wrong About How It Works

Then there’s the diaphragm. It’s a dome-shaped sheet of muscle that separates your chest from your gut. When it contracts, it flattens out. This creates that vacuum I mentioned earlier. Most people are "chest breathers," using their shoulders and upper ribs too much, which is inefficient. "Belly breathing" is actually just using the diaphragm correctly. When the diaphragm drops, your stomach pushes out because there’s nowhere else for your organs to go. It’s a tight squeeze in there.

The Inner Sanctum: Heart and Lungs

If the ribs are the walls of the house, the heart and lungs are the inhabitants. They are protected by the pleura—a thin, double-layered membrane. Think of it like a plastic bag with a little bit of grease inside. It allows the lungs to slide against the ribcage without friction. If that gets inflamed, you get pleurisy, which feels like being stabbed every time you take a breath.

The heart sits in the mediastinum. That’s just the fancy name for the middle space between the lungs. It’s not actually on the far left of your chest; it’s mostly central but tilted, with the "apex" or bottom point aimed toward the left. This is why you feel the heartbeat more strongly on that side. Around it is the pericardium, another protective sac.

- Right Lung: Has three lobes (superior, middle, inferior). It’s shorter because the liver sits right underneath it.

- Left Lung: Has only two lobes. It’s narrower because it has to make room for the "cardiac notch"—basically a cutout for the heart to sit in.

- The Pipes: The trachea (windpipe) splits into two bronchi, which then branch out like a tree into smaller and smaller tubes until they reach the alveoli. This is where the magic of gas exchange happens.

What People Get Wrong About Chest Pain

Usually, when someone feels a twinge in their chest, they immediately think "heart attack." While you should never ignore chest pain, the anatomy of the human chest offers a dozen other culprits.

Costochondritis is a huge one. This is just inflammation of the cartilage connecting the ribs to the breastbone. It can feel sharp, stabbing, and terrifyingly like a cardiac event, but it’s actually just a musculoskeletal issue. It’s common after a viral infection or heavy lifting.

Then there’s the esophagus. It runs right down the middle, behind the trachea. Acid reflux can cause "heartburn" that mimics a heart attack because the nerves in the chest are a bit messy. They aren't very good at pinpointing exactly where pain is coming from. This is called "referred pain." It’s why a gallbladder issue can sometimes cause pain in your right shoulder or chest. The brain gets the signals crossed.

👉 See also: Ankle Stretches for Runners: What Most People Get Wrong About Mobility

The Neurovascular Bundle: Nature's Wiring

Underneath every single rib, there’s a little groove. Inside that groove sits a vein, an artery, and a nerve. This is the neurovascular bundle.

Medical professionals are trained to always insert needles or chest tubes above a rib, never below it. If you go below, you hit that bundle. That’s a mistake you only make once in a simulation lab before you realize how much blood—and how much pain—that causes. These nerves are responsible for the "shingles" pain people experience; the virus lives in the nerve roots and follows the path of the rib, creating a literal wrap-around belt of rash and pain.

Evolution and the "Weak Spots"

We’ve evolved to protect the "vitals," but there are gaps. The lower ribs are more prone to breaking because they aren't anchored to the sternum. A broken rib isn't just a bone issue; it’s a breathing issue. If a rib breaks in two places (a condition called flail chest), that segment of the chest moves inward when you breathe in, and outward when you breathe out. It’s called paradoxical breathing, and it’s a top-tier medical emergency.

Also, look at the "thoracic outlet." This is the space at the very top of your chest where all the nerves and blood vessels go into your arm. If your posture is trash or you have an extra "cervical rib" (about 1 in 500 people do), these pipes get pinched. You get numb hands, cold fingers, and weakness. It’s a reminder that the anatomy of the human chest isn’t isolated—it’s the gateway to the rest of your body.

Surprising Facts About Your Thorax

Did you know your lungs aren't identical? Or that your heart can actually rotate slightly within its sac?

The human chest is also a pressure regulator. When you strain (like lifting a heavy weight or, let's be honest, sitting on the toilet), you perform a Valsalva maneuver. You close your glottis and contract your chest muscles. This spikes the pressure inside your chest, which actually slows your heart rate down by stimulating the vagus nerve. It’s a built-in "reset" button for the body.

✨ Don't miss: Can DayQuil Be Taken At Night: What Happens If You Skip NyQuil

Another weird thing: the "thymus." In kids, this gland sits right behind the sternum and is huge. It’s the training ground for the immune system. By the time you’re an adult, it mostly turns into a blob of fat. It’s done its job and retired, though some research suggests it still plays a minor role in T-cell production late into life.

Taking Care of Your Internal Architecture

So, how do you actually maintain the anatomy of the human chest? It’s not just about bench pressing.

First, posture matters more than you think. Slumping forward compresses the thoracic cavity. It limits the diaphragm’s range of motion, which means you’re taking shallower breaths. Shallow breathing triggers the sympathetic nervous system—the "fight or flight" mode. Basically, sitting like a shrimp makes you more stressed.

Second, mobility is king. Stretching the "thoracic spine" (the part of your back where the ribs attach) keeps the whole cage fluid. If your mid-back gets stiff, your ribs can’t move. If your ribs can’t move, your shoulders and neck have to take up the slack, leading to chronic pain in places that seem totally unrelated to your chest.

Actionable Steps for Better Chest Health

Stop thinking of your chest as just a surface for muscles and start treating it like the pressurized engine it is.

- Test your expansion: Wrap a tape measure around your chest just below the armpits. Exhale fully, then take the deepest breath possible. A healthy adult should see an expansion of 2 to 3 inches. Less than that? You might need to work on rib mobility or see a doctor about potential restrictive issues.

- The Doorway Stretch: Stand in a doorway, place your forearms on the frame, and lean forward. This opens the pectorals and the intercostals. Do this after every hour of sitting at a desk.

- Diaphragmatic Breathing: Lie on your back. Put one hand on your chest and one on your belly. Breathe so only the hand on your belly moves. Do this for 5 minutes a day to "re-train" your primary breathing muscle.

- Monitor "Twinges": If you have chest pain that changes when you push on it with your finger, it’s likely muscular or cartilaginous. If it’s a deep, crushing pressure that doesn't change when you move or push, that’s your signal to head to the ER immediately.

The anatomy of the human chest is the literal center of your being. It’s the bridge between the air outside and the blood moving through your veins. Respect the cage, keep the joints moving, and don't ignore the signals it sends you. Whether it's a "stitch" in your side while running or a tightness from stress, your thorax is always talking. It pays to listen.