You’ve seen them standing tall against a fence or nodding their heads in a summer breeze. They look simple. A yellow circle on a green stick. But honestly, the anatomy of a sunflower is one of the most deceptive and complex engineering feats in the plant kingdom. What you think is "a flower" is actually thousands of them. It's a crowded neighborhood, not a single house.

Most people walk past a Helianthus annuus and think they’re looking at a giant daisy. They’re not. They are looking at a "pseudanthium," or a false flower. If you’ve ever tried to grow these things, you know they are greedy. They drink water like they’re trying to drain the local aquifer and they chase the sun with a weird, almost animal-like obsession. Understanding how they’re built explains why they grow six inches in a week and how they manage to produce hundreds of oil-rich seeds without breaking a sweat.

The Big Lie: It’s Not One Flower

Let’s get the biggest misconception out of the way immediately. The "head" of the sunflower is a composite structure. It’s a community.

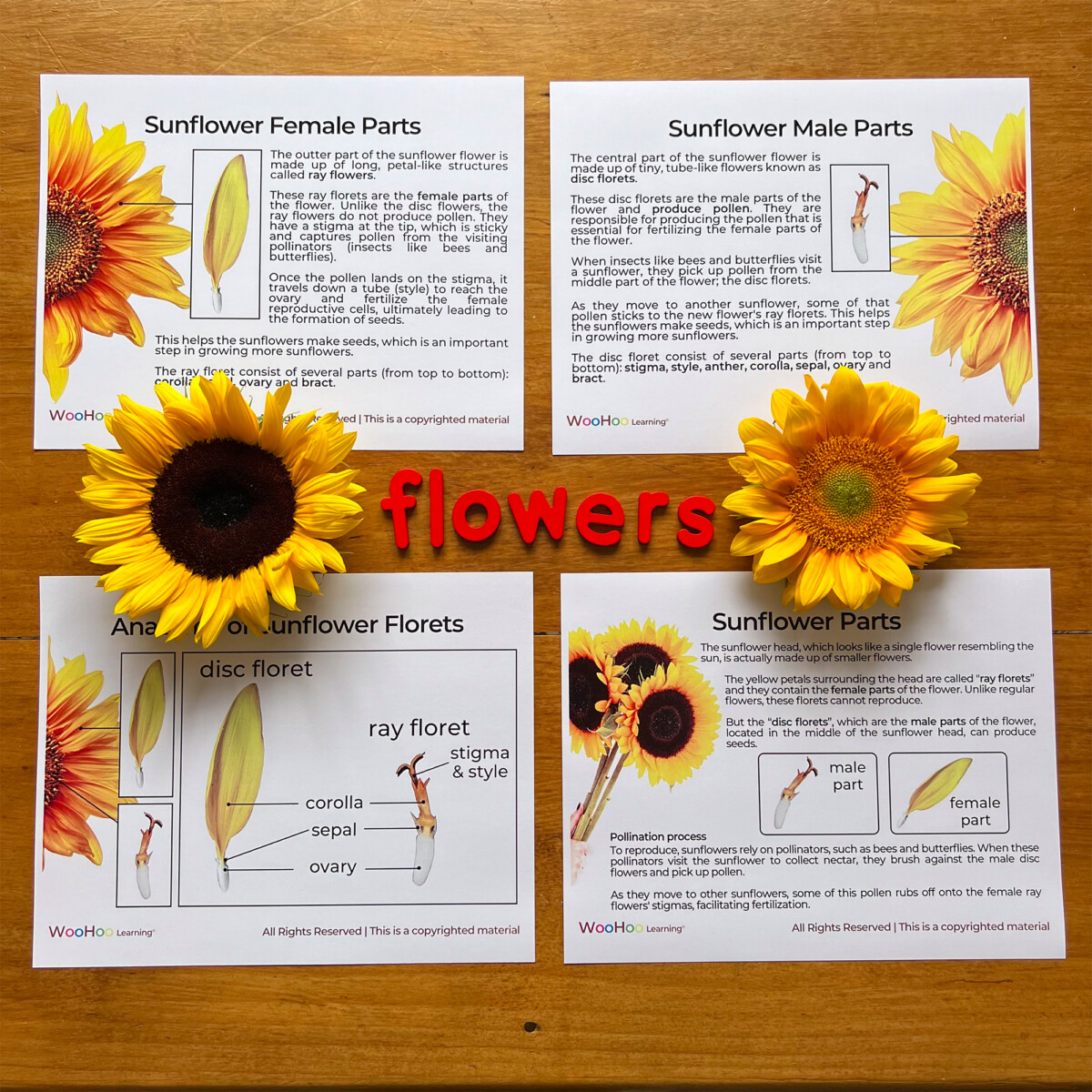

If you peel back the anatomy of a sunflower head, you’ll find two very different types of flowers working together. First, you have the ray florets. These are the long, vibrant yellow "petals" on the outside. Here’s the kicker: they are sterile. They can’t make seeds. Their entire job is basically marketing. They exist solely to wave down bees and butterflies, screaming "Hey, there’s food over here!"

Then you have the disc florets.

These are the tiny, brownish-purplish tubes packed into the center. This is where the magic happens. A single sunflower head can contain anywhere from 1,000 to 2,000 of these individual flowers. Each one has its own ovary, its own stamen, and its own stigma. When you eat a sunflower seed, you are eating the matured ovary of a single, tiny disc floret.

They don't all bloom at once. That would be a waste of energy. Instead, they bloom in a spiral pattern starting from the outside and moving toward the center. It’s a slow-motion explosion of fertility that ensures pollinators have a reason to keep coming back for days.

Fibonacci and the Mathematical Heart

Ever looked at the center of a sunflower and felt a bit dizzy? There’s a reason. The disc florets aren't just shoved in there randomly. They follow a very specific mathematical pattern called the Fibonacci sequence.

💡 You might also like: Why Every Mom and Daughter Photo You Take Actually Matters

Basically, the flowers are arranged in two sets of spirals—one going clockwise and the other counter-clockwise. Usually, you’ll see 34 spirals going one way and 55 the other. In giant varieties, it might be 89 and 144. This isn't the plant being fancy; it's about packing efficiency. By following this geometric rule, the sunflower fits the maximum number of seeds into the smallest possible space without leaving any gaps.

Nature is a minimalist architect.

The Stem: More Than a Green Pipe

The stem is the backbone. It has to be. If you’re growing a Russian Giant that’s pushing 12 feet tall, that stem is supporting a massive amount of weight, especially after a rainstorm when the flower head acts like a giant sponge.

Inside that green pillar, you’ll find a complex vascular system. Sunflowers are "dicots," meaning their vascular bundles (the tubes that carry water and sugar) are arranged in a ring. This gives the stem incredible structural integrity. Think of it like the steel rebar in a skyscraper.

- Xylem: This moves water from the roots up to the leaves.

- Phloem: This carries the "food" (sugars) created in the leaves down to the rest of the plant.

- Pith: The center of the stem is filled with a spongy tissue called pith. In some older varieties, this was actually used as a buoyancy aid because it's so light and airy.

Heliotropism: The Sun-Chasing Muscle

One of the coolest parts of the anatomy of a sunflower isn't a physical part you can just point to—it's how the stem moves. People call this heliotropism.

Young sunflowers follow the sun. In the morning, they face east. By sunset, they’ve cranked their heads all the way to the west. At night, they reset and turn back to the east to wait for dawn. How? It’s not a muscle. It’s differential growth.

The stem has cells that elongate faster on the "shadow" side. This uneven growth literally pushes the head of the flower over. It’s a constant tug-of-war between the sides of the stem. Once the flower matures and the stem hardens into woodier tissue, the movement stops. Mature sunflowers almost always stay fixed facing east.

📖 Related: Sport watch water resist explained: why 50 meters doesn't mean you can dive

Why east? Because it’s warmer.

Studies, including research from the University of California, Davis, have shown that bees prefer warm flowers. An east-facing sunflower heats up faster in the morning sun, attracting five times more pollinators than a flower facing west. It’s all about the hustle.

The Root System: The Silent Anchor

You can’t talk about the anatomy of a sunflower without looking at what’s happening underground. It’s massive.

Sunflowers have a taproot system. The primary root can plunge three to four feet straight down into the dirt. Branching off that are thousands of smaller lateral roots. This is why sunflowers are surprisingly drought-tolerant once they get established. They aren't just sipping from the surface; they are mining for water deep in the subsoil.

But there’s a dark side. Sunflowers are allelopathic.

They actually leak chemicals from their roots (and leave them behind in their fallen leaves) that inhibit the growth of other plants. They are bullies. If you’ve ever wondered why the grass looks a bit pathetic underneath your bird feeder where the sunflower shells land, that’s why. The plant is literally poisoning the competition to ensure it has all the nitrogen and phosphorus for itself.

Leaves: The Solar Panels

The leaves are huge. On some varieties, they are broader than a dinner plate. They are covered in tiny, stiff hairs called trichomes.

👉 See also: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

If you rub a sunflower leaf, it feels like sandpaper. These hairs aren't just there to be annoying; they serve a few purposes:

- They deter insects that don't want a mouthful of prickles.

- They break up the wind, preventing the leaf from losing too much moisture through transpiration.

- They help the plant trap a thin layer of humid air against the leaf surface.

The leaves are arranged in an "alternate" pattern on the stem. This ensures that the top leaves don't completely shade out the bottom ones. Every leaf gets its moment in the sun.

Bracts: The Unsung Protectors

Look at the back of a sunflower head. You’ll see green, leaf-like structures overlapping like scales on an artichoke. These are bracts, or more specifically, "phyllaries."

In the early stages of the anatomy of a sunflower, these bracts are tightly closed, protecting the delicate developing florets from predators. As the flower opens, they peel back. They contain chlorophyll, so they actually contribute a bit of energy to the plant through photosynthesis, but their main job is defense. They are the armor plating for the seeds.

The Life Cycle Inside the Anatomy

Once a bee lands on the disc florets, it moves pollen from the male anthers to the female stigma. The pollen grain grows a tube down into the ovary. Fertilization happens.

The floret then withers, and the ovary begins to swell. This is the seed development phase. The "shell" of a sunflower seed is technically the pericarp. Inside that shell is the "kernel," which is the actual embryo.

The sheer weight of a thousand developing seeds is what causes the iconic "droop" of a late-season sunflower. The stem stays strong, but the neck (the peduncle) curves under the gravitational pull of the next generation. It’s the plant’s way of protecting the seeds from birds and the elements until they are fully dry and ready to drop.

Putting Knowledge into Action

If you’re growing sunflowers or just studying them, keep these specific anatomical quirks in mind to get the best results:

- Space them out: Because of their allelopathic roots, don't plant delicate vegetables right up against them. Give them at least 12 inches of "buffer" zone.

- Support the stem: If you live in a windy area, the vascular strength of the stem might not be enough for giant heads. Stake them early, before the heliotropism stops and the stem becomes brittle.

- Check the bracts for pests: If you see "bleeding" or sap on the green bracts at the back of the head, you likely have sunflower moths. They lay eggs there, and the larvae will tunnel into the seeds.

- Harvesting: Wait until the back of the head (the bracts) turns from green to yellow-brown. This indicates the vascular connection to the seeds has closed, and the fats in the seeds are fully developed.

- Feed the soil: Remember, these are heavy feeders. They pull a massive amount of potassium and nitrogen out of the soil to build that thick stem and oily seeds. Always replenish your soil with compost after the season ends.

Sunflowers are more than just a pretty face in the garden. They are highly efficient, mathematically precise, and slightly aggressive biological machines designed to turn sunlight into oil as fast as possible. Once you see the thousands of tiny flowers hiding in the center, you'll never look at a "single" sunflower the same way again.