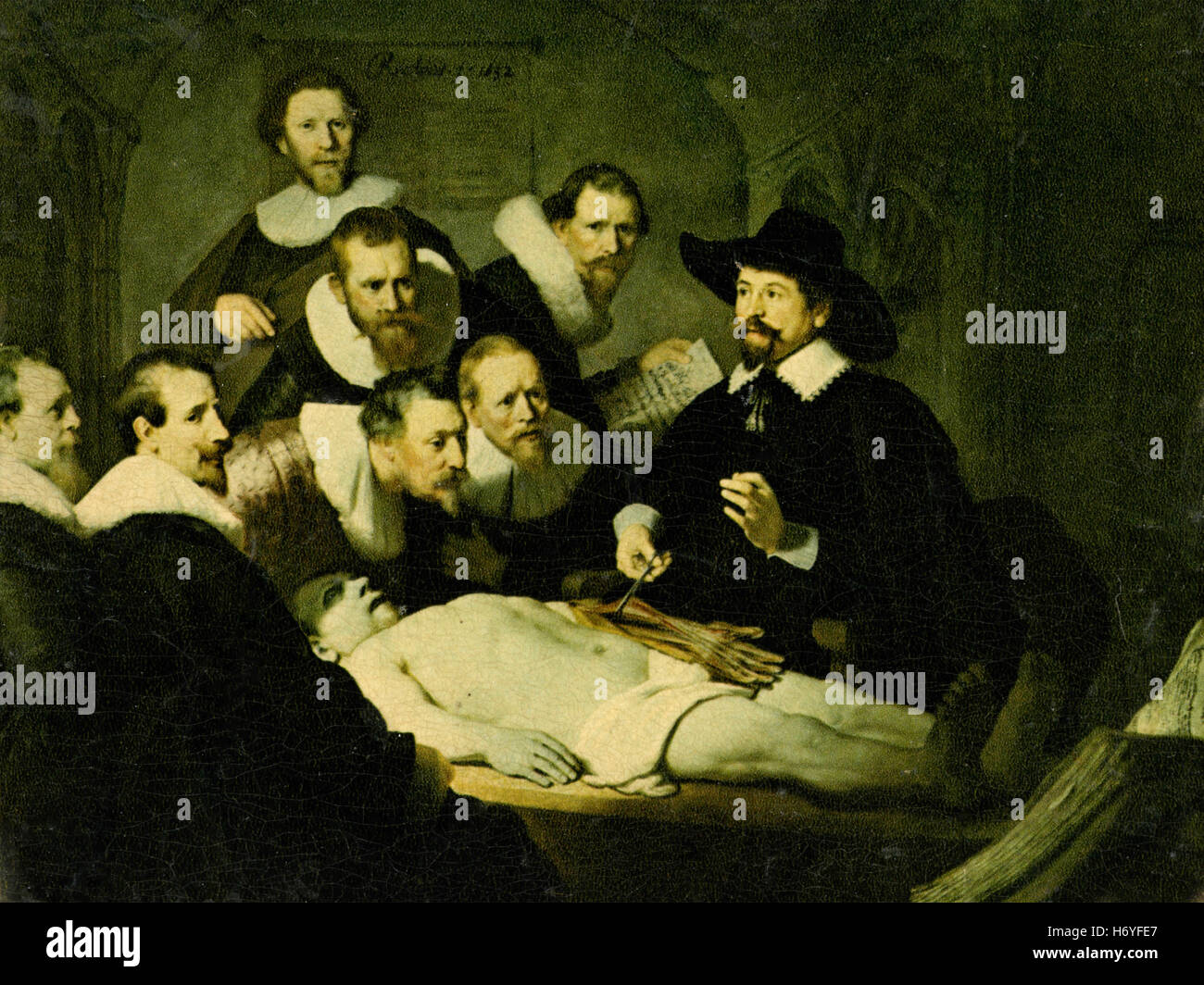

You’ve probably seen it in a textbook or on a dorm room poster. A group of men in oversized white collars leaning over a very pale, very dead body. It’s moody. It’s dramatic. Honestly, it’s a bit creepy. The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, painted by a twenty-six-year-old Rembrandt van Rijn in 1632, isn't just a masterpiece; it’s basically the 17th-century version of a high-stakes corporate headshot.

But here is the thing: if you actually look at the "science" in the painting, things start to get weird. Like, "anatomically impossible" weird. For a painting that’s supposed to celebrate the dawn of modern medicine, Rembrandt took some massive liberties with the truth.

Why the Anatomy Lesson Painting Rembrandt Created is Factually "Broken"

If you were a medical student in the 1630s and you tried to use this painting as a cheat sheet, you’d fail your exams. Big time. Modern surgeons and researchers, like those at the University of Groningen, have spent way too much time pointing out that the arm being dissected—the focal point of the whole piece—is kind of a disaster.

The most famous "oops" moment? The tendons. Dr. Tulp is shown using forceps to lift a specific set of muscles (the flexor digitorum superficialis, for those keeping score). In the painting, these muscles appear to originate from the lateral epicondyle (the outside of the elbow). In a real human body? They grow from the medial epicondyle (the inside).

💡 You might also like: Why Pop It Fidget Toys Are Still Everywhere

Basically, Rembrandt painted the arm backward or inside out.

Some art historians, like Jean-Marie Clarke, argue this wasn't a mistake at all. They think Rembrandt was being "meta." There’s this theory that the navel of the corpse is shaped like a capital "R"—a secret signature. Others think he was just copying a diagram from a textbook like Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica and accidentally mirrored it.

Whatever the reason, the "lesson" is a bit of a lie.

The Corpse Had a Name: Meet Aris Kindt

We talk about Tulp and Rembrandt, but we rarely talk about the guy on the table. He wasn't some anonymous medical volunteer. His name was Aris Kindt (an alias for Adriaan Adriaanszoon).

Kindt wasn't exactly a saint. He was a career criminal who had just been hanged earlier that day for armed robbery. Specifically, he’d mugged a guy for his cloak. In 17th-century Amsterdam, the Surgeons' Guild was only allowed one public dissection per year, and the rules were strict: it had to be an executed male criminal.

💡 You might also like: Finding Japan in Lancaster SC: Where to Get Real Sushi and Hibachi Without the Drive

A few grim details about Aris Kindt:

- He was executed on January 31, 1632.

- He had a long "rap sheet" before the final robbery.

- In early X-rays of the painting, his right hand was originally a stump.

- Why? Because as part of his punishment for a previous crime, his right hand had been chopped off before he was eventually hanged.

Rembrandt later painted a hand over that stump to make the painting look "nicer." It’s a weirdly empathetic move for a guy who was basically painting a trophy for the doctors.

It Was Actually a 17th-Century "Pay-to-Play" Scheme

You might think these seven guys gathered around the body are Tulp's most dedicated students. Wrong. They’re the guys who had the cash.

The Surgeons' Guild commissioned this as a group portrait. Every person in that painting, except for the corpse and Dr. Tulp, had to pay Rembrandt a fee to be included. If you paid more, you got a better spot. That’s why some guys are leaning in close while others are just staring off into space like they’re bored.

The guy at the very top, Frans van Loenen, was actually added late or had his hat painted out because only Tulp was allowed to wear a hat. It was a status thing. The hat showed Tulp was the "Praelector" (the boss). Everyone else was just background noise with deep pockets.

The "Social Media" of the 1600s

Anatomy lessons weren't quiet, somber affairs. They were total circuses.

These dissections happened in "Anatomy Theatres." You had to buy a ticket. People brought snacks. It was cold (they only did this in winter so the body wouldn't rot as fast), and the air was thick with the smell of incense and coal fires to mask the stench of Aris Kindt.

Rembrandt ignores all that. He strips away the crowds, the snacks, and the nosey neighbors to make it look like a holy, intellectual moment. He uses chiaroscuro—that extreme contrast between light and dark—to make the dead guy look almost glowing.

It’s not a documentary. It’s an advertisement for the "Age of Reason."

What You Should Actually Do With This Information

Next time you’re in The Hague at the Mauritshuis (where the painting lives), or even if you’re just looking at a high-res scan online, don't just look at the faces. Look at the "paper" one of the men is holding. It’s a list of the donors—the guys who paid for the painting.

Actionable Insights for Art Lovers:

- Check the Eyelines: Notice that almost nobody is actually looking at the arm. They’re looking at the anatomy book at the foot of the bed. They’re more interested in the theory than the actual messy reality of the body.

- Look for the "R": Squint at the corpse's belly button. Is it a signature or just a weird shadow? Scholars are still arguing about it.

- Spot the Fake Hand: Compare the right hand of the corpse to the left one. The right one is darker and looks a bit "stuck on" because, well, it was.

Rembrandt’s anatomy lesson painting proves that even the greatest artists in history weren't afraid to "fake it 'til they made it." He gave the doctors what they wanted: a scene that looked smart, expensive, and important, even if the muscles were attached to the wrong side of the arm.