In 1914, if you asked a random person on a street corner in Topeka or Boston about the Red Cross, you might get a blank stare. It was tiny. Really tiny. We’re talking about an organization that had a few dozen local chapters and a headquarters staff you could fit into a single dining room. Then the "Great War" happened. By the time the 1918 Armistice was signed, the american red cross world war 1 effort had fundamentally changed how the United States viewed its responsibility to the rest of the world. It wasn’t just about bandages. It was about a massive, grassroots explosion of volunteerism that basically turned every kitchen and church basement in America into a mini-factory for the war effort.

The Massive Scale of the American Red Cross World War 1 Mobilization

Numbers usually bore people. I get it. But the sheer leap the Red Cross took between 1917 and 1919 is actually staggering. Before the U.S. entered the fray, the Red Cross had maybe 200,000 members. Within months of the declaration of war, that number skyrocketed to over 20 million adults and another 11 million kids in the Junior Red Cross.

Think about that.

Nearly one-third of the entire U.S. population was paying dues or volunteering for this one organization. President Woodrow Wilson didn’t just give it a thumbs up; he basically integrated it into the military machine. He appointed a "War Council" led by Henry P. Davison, a partner at J.P. Morgan. Davison didn't think small. He treated the Red Cross like a massive corporate merger, raising $115 million in a single week-long fund drive in 1917. That’s billions in today’s money. It was the first time Americans saw a massive, coordinated "brand" campaign for a cause.

The "Production Line" in the Living Room

The war wasn't just fought in the trenches of France; it was fought by women knitting socks in Ohio. The Red Cross realized early on that the U.S. military wasn't equipped to provide everything a soldier needed. They turned to the public. They issued specific patterns for "comforts"—sweaters, mufflers, and specifically, socks. If a soldier's feet got wet and stayed wet, he got trench foot. If he got trench foot, he couldn't fight. So, the "Knitting for Victory" campaign became a literal lifeline.

Millions of surgical dressings were handmade by volunteers. In a world before mass-produced disposable medical supplies, these "front-line" women were the ones rolling bandages by hand. They produced over 300 million surgical dressings during the war. Imagine the blisters. Honestly, the logistical feat of collecting these items from thousands of tiny towns and shipping them across an ocean infested with U-boats is one of the most underrated achievements of the 20th century.

👉 See also: Sport watch water resist explained: why 50 meters doesn't mean you can dive

Realities of the Front Line and the Nursing Corps

When we talk about the american red cross world war 1 experience, we have to talk about the nurses. Jane Delano, the head of the Red Cross Nursing Service, was a powerhouse. She mobilized over 20,000 registered nurses to serve with the Army and Navy Nurse Corps. These women weren't just sitting in back-row hospitals. They were in evacuation stations, often under fire, dealing with the horrifying effects of mustard gas and high-explosive artillery.

They saw things no one should see.

- Shattered limbs from new, industrial-grade weaponry.

- The gasping, drowning sensation of soldiers whose lungs were burned by chemical agents.

- The psychological "shell shock" that doctors were only just beginning to name.

The Red Cross also ran canteens. These weren't just coffee shops. They were "huts" where a soldier could get a hot meal, a dry place to sit, and a chance to write a letter home. For many 19-year-olds who had never left their county before being shipped to a muddy hole in the Argonne Forest, the sight of a Red Cross worker was the only thing that felt like home.

The 1918 Flu: A Second Front

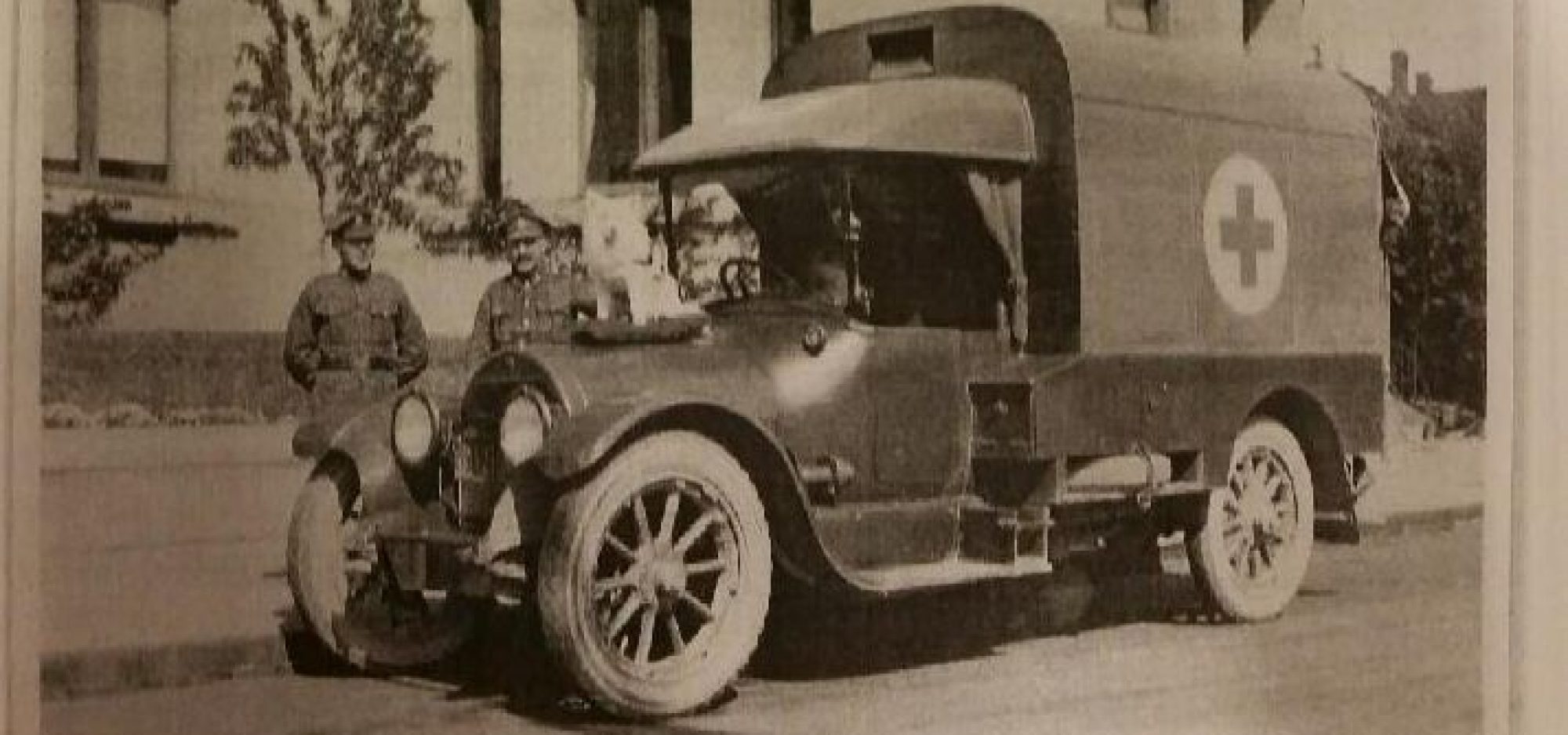

Just as the war was reaching its climax, the "Spanish Flu" hit. This is where the Red Cross really shifted from a "war support" group to a public health savior. The pandemic killed more people than the war did. In the U.S., Red Cross chapters became the primary responders. They set up emergency hospitals, organized "motor corps" to transport the sick, and made millions of gauze masks.

It was chaotic.

✨ Don't miss: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

The Red Cross Nursing Service was stretched to the breaking point. Many nurses who survived the horrors of the Western Front came home only to die of the flu while treating patients in their own neighborhoods. This period solidified the Red Cross as the "go-to" agency for domestic disasters, a role they still hold today.

Communication: The Home Communication Service

One of the coolest—and most heartbreaking—things the american red cross world war 1 teams did was act as a human telegram service. Back then, you couldn't just FaceTime your mom from a bunker. If a soldier was wounded or missing, the official military telegram was often vague and terrifying.

The Red Cross Home Communication Service stepped in.

They had workers in hospitals who would sit by the beds of wounded soldiers and write letters for them. If a soldier died, these workers would often write to the families to give them details the military didn't provide—who was with him, if he was in pain, what his last words were. It sounds small, but for a mother in rural Nebraska, that letter was everything. It was the only closure they would ever get.

What People Get Wrong About the Red Cross in WWI

A lot of people think the Red Cross was a government agency. It wasn't. It was (and is) a private organization with a congressional charter. This distinction mattered because it allowed them to be flexible. They could do things the Army bureaucracy couldn't, like setting up "Recreation Huts" or providing library books to bored troops.

🔗 Read more: Hairstyles for women over 50 with round faces: What your stylist isn't telling you

Another misconception is that they only helped "our guys." While their primary focus was definitely the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), the Red Cross was active in helping civilian populations across Belgium, France, and Italy. They ran dispensaries for kids, helped refugees find lost family members, and provided seeds to farmers whose fields had been turned into moonscapes by shells.

The Dark Side: Racism and the Blood Limit

We have to be honest about the era. The Red Cross, like the military it supported, was segregated. Black nurses struggled to be accepted into the service, despite their qualifications. It wasn't until the very end of the war, and particularly during the flu pandemic, that the barriers started to crack—but they didn't break. Even the "Donut Dollies" and canteen workers were largely part of a system that reflected the deep-seated prejudices of 1910s America. Acknowledging this doesn't diminish the good they did, but it gives a fuller, more human picture of the time.

How the War Changed the Organization Forever

Before 1917, the Red Cross was a niche charity. After 1919, it was a national institution. They had learned how to market. They had learned how to manage millions of volunteers. Most importantly, they had established the "Junior Red Cross," which taught a whole generation of children that being a citizen meant helping people you've never met in countries you've never seen.

The war ended, but the Red Cross didn't go back to its small roots. They shifted to "peace-time" work, focusing on public health, water safety (yes, that’s why you took Red Cross swimming lessons), and disaster relief. The infrastructure built to fight the Kaiser became the infrastructure used to fight fires, floods, and poverty.

Actionable Ways to Explore This History Today

If you’re a history buff or just curious about how this era shaped your own family, you don't have to just read a book. There are some really practical things you can do to connect with this legacy.

- Search the National Archives: The records of the American Red Cross (Record Group 200) are massive. You can often find digitized photographs and even reports from specific local chapters. If your great-grandmother volunteered, her name might be in a local ledger.

- Visit the Red Cross Square in D.C.: The national headquarters is actually a memorial to the women of the Civil War, but the buildings themselves are steeped in WWI history. It's a quiet, powerful place that feels very different from the usual tourist stops.

- Check Local Museum Archives: Many small-town historical societies have "Red Cross posters" or hand-knitted items from the era. Seeing a 100-year-old sock that was meant for a soldier in the Meuse-Argonne makes the history feel a lot less "textbook" and a lot more real.

- Volunteer or Donate: It sounds cliché, but the Red Cross still operates on the same basic principle it did in 1917—public support. Whether it's giving blood or helping with disaster relief, you're participating in a chain of service that was forged in the mud of the Western Front.

The american red cross world war 1 story isn't just about the past. It’s about the moment America decided to show up for the rest of the world. It was messy, it was massive, and it was driven by regular people who decided that "doing their bit" was the only way forward. That spirit of radical volunteerism changed the country's DNA. We still see the ripples of that change every time a disaster strikes and people reach for their wallets or roll up their sleeves.

To really understand the Red Cross today, you have to look back at those women in the white veils and the millions of people who spent their evenings knitting by candlelight. They didn't just save lives; they built a system of compassion that was big enough to handle a world on fire. It's a legacy that’s worth remembering, not as a dry chapter in a history book, but as a living example of what happens when a whole nation decides to care about something bigger than itself.