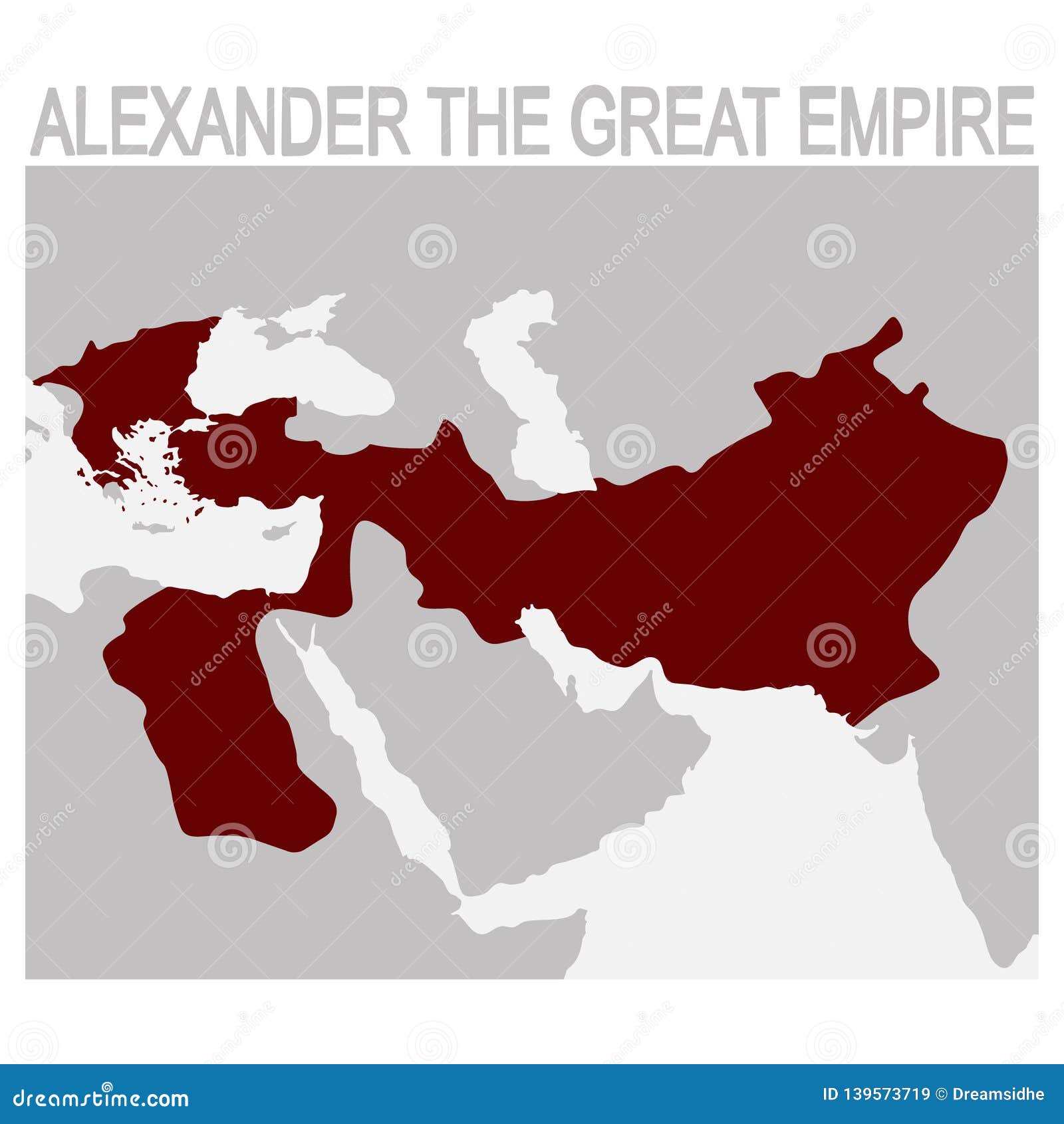

He was 20. When Alexander III of Macedon took the throne, most people figured he’d just be another footnote in Greek squabbling. Instead, he drew a line across the world that never quite faded. If you look at an Alexander the Great map today, it looks like someone spilled ink from Greece all the way to the edge of the Himalayas. It’s messy. It’s massive. Honestly, it’s kind of ridiculous when you realize he did it all in about 12 years without a single GPS satellite or a decent pair of boots.

We’re talking about three million square miles.

Most people think he just marched straight east, but the actual route was a jagged, zig-zagging mess of ego and strategy. He wasn't just conquering; he was exploring. He brought scientists, botanists, and geographers with him. They were literally measuring the world with their feet—men called "bematists" who counted their steps to map out distances. It’s wild to think that our modern understanding of Middle Eastern geography started with a guy counting "one, two, three" while dodging Persian arrows.

Why the Alexander the Great Map keeps changing in history books

If you open five different history books, you’ll probably see five slightly different versions of the Alexander the Great map. Why? Because borders back then weren't lines on the ground; they were spheres of influence.

Take the Siege of Tyre in 332 BCE. Alexander wanted to get to Egypt, but Tyre—a city on an island—was in his way. He didn't just sail around it. He built a literal land bridge to the island. He changed the physical map of the earth. Even today, that "island" is a peninsula because of the silt that gathered around his causeway. When we look at his empire's reach, we have to look at these specific "choke points" where he forced the geography to submit to his will.

The Granicus to Gaugamela stretch

The first real chunk of the map starts in Asia Minor—modern-day Turkey. He smashed the Persians at Granicus, then again at Issus. If you're looking at the map, notice how he hugs the coast. He knew the Persian navy was better than his, so he "conquered the sea from the land" by taking every single port. Clever, right? He basically turned the Mediterranean into a Macedonian lake before he ever stepped foot in the deep desert.

Then comes the heart of the empire: Babylon, Susa, and Persepolis. This is where the map gets complicated. He wasn't just moving an army; he was moving a city. By the time he reached the Persian Gates, his "map" included tens of thousands of camp followers, traders, and even philosophers.

👉 See also: Flights from San Diego to New Jersey: What Most People Get Wrong

The "End of the World" and the turn back at the Hyphasis

By 326 BCE, the Alexander the Great map had reached its breaking point. Alexander wanted to see the "Outer Ocean." He genuinely believed that just over the next hill in India, he’d find the edge of the world.

He didn't.

He found the Punjab. He found monsoon rains that rotted his men's clothes and rusted their swords. He found King Porus and a wall of war elephants. But the real reason the map stops at the Hyphasis River (now the Beas River) isn't because he lost a battle. He never lost. It’s because his men looked at the infinite horizon and said, "Nope." They staged a mutiny.

They were tired. They were homesick. They were thousands of miles from Pella.

The retreat through the Gedrosian Desert is one of the darkest parts of the map. It was a shortcut that turned into a death march. Thousands died of thirst and heat exhaustion. If you look at a topographical map of his return route, you can see the desperation. He wasn't conquering anymore; he was just trying to survive the geography he’d claimed.

Alexandria: The dots on the map that stayed

You can’t talk about the Alexander the Great map without mentioning the Alexandrias. He founded something like 70 cities. Most of them he named after himself. One he named after his horse, Bucephalus.

✨ Don't miss: Woman on a Plane: What the Viral Trends and Real Travel Stats Actually Tell Us

- Alexandria in Egypt: The big one. The center of learning for centuries.

- Alexandria Eschate: Literally "Alexandria the Furthest" in modern Tajikistan.

- Alexandria on the Caucasus: Near modern-day Bagram, Afghanistan.

These weren't just forts. They were cultural time bombs. He left behind Greek soldiers who married local women, creating a weird, beautiful hybrid culture called Hellenism. This is why you find statues of the Buddha in Pakistan dressed in Greek-style robes. The map didn't just show where he went; it showed where the West met the East for the first time in a meaningful way.

What most maps get wrong about the Persian Empire

There’s this misconception that Alexander conquered a vacuum. He didn't. He inherited the Achaemenid Empire.

The Persians had incredible roads—the Royal Road was basically the interstate system of the 4th century BCE. Alexander used their maps, their messengers, and their infrastructure. Honestly, his empire was just the Persian Empire under new management. He even started wearing Persian clothes and demanding people bow to him, which drove his Macedonian friends absolutely insane.

When you study the Alexander the Great map, you're really looking at a layer of Greek paint over a Persian canvas. The borders of his satrapies (provinces) were largely the same ones Cyrus the Great had established 200 years earlier.

The chaos after Babylon

Alexander died in 323 BCE in Babylon. He was 32. He didn't leave a will, or at least not a clear one. When asked who should get the empire, he supposedly said, "To the strongest."

That was a disaster.

🔗 Read more: Where to Actually See a Space Shuttle: Your Air and Space Museum Reality Check

The map immediately shattered. His generals, the Diadochi, spent the next several decades tearing the map into pieces.

- Ptolemy took Egypt (starting the line that ended with Cleopatra).

- Seleucus took the vast Asian territories (the Seleucid Empire).

- Antigonus and others fought over Greece and Macedon.

The unified Alexander the Great map lasted for about five minutes after his heart stopped beating. But the influence? That lasted for a thousand years. Roman maps were based on his. Islamic cartographers studied his routes. Even Napoleon carried books about Alexander when he invaded Egypt.

How to use this history today

If you’re a history buff or a traveler, don't just look at the map as a static image. Look at it as a travel itinerary. Many of the cities he founded or conquered are still massive hubs today.

- Check out the Siwa Oasis: Go where Alexander went to talk to the Oracle of Ammon. It’s a trek, but the ruins are there.

- Visit the Hindu Kush: Imagine trying to move 40,000 men over those peaks in the winter without modern gear.

- Look for the "Gordian Knot" site: It’s near Ankara, Turkey. Whether he actually cut the knot or just pulled the pin out, the site represents the moment he decided the map belonged to him.

The real takeaway from the Alexander the Great map isn't just about the miles. It's about the fact that before him, the world was a series of disconnected bubbles. After him, everyone knew everyone else existed. He forced the world to acknowledge its own scale.

To really understand the geography, you should cross-reference his route with a modern map of the Silk Road. You'll see that he basically paved the way for the greatest trade route in human history. He didn't just draw a map; he opened a door that stayed open for two millennia.

Next time you're looking at a map of Central Asia or the Middle East, look for the jagged lines. Look for the cities that seem just a bit too "planned." Usually, if you dig deep enough into the dirt of a city like Herat or Kandahar, you’ll find a Greek coin or a piece of a column that proves a 20-something kid from Macedonia was there first.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Compare Terrains: Use Google Earth to trace the route from the Khyber Pass to the Indus River. Seeing the verticality of the landscape explains why his army finally broke.

- Study the Diadochi: If you want to see where modern Middle Eastern borders actually began, research the "Successor Kingdoms" that formed after 323 BCE.

- Read the Sources: Pick up Arrian’s Anabasis of Alexander. It’s the closest thing we have to a contemporary military log of the march.