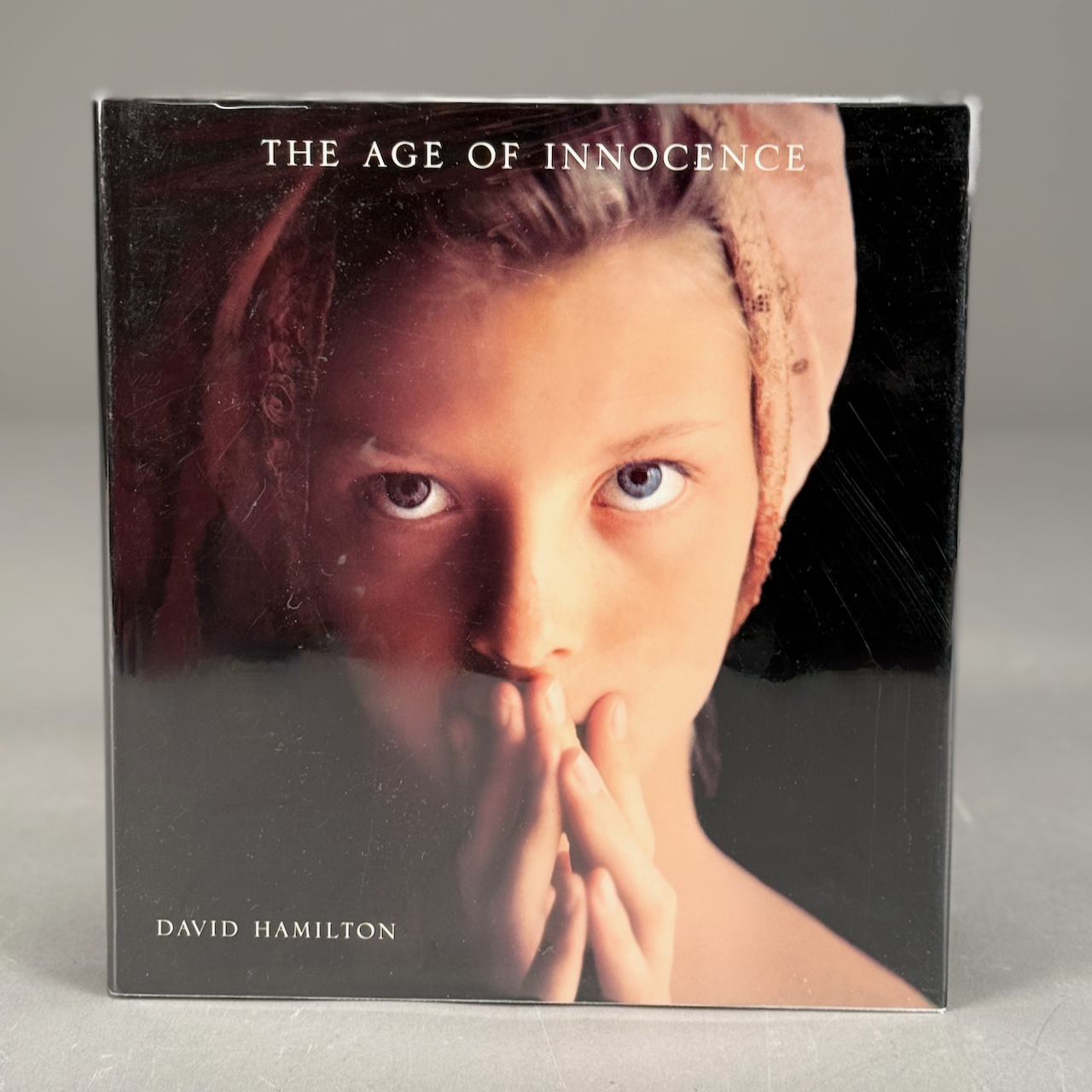

Walk into any high-end vintage bookstore and you might find it. A heavy, cloth-bound spine. Maybe a bit of dust. It's a copy of The Age of Innocence by David Hamilton. For some, it’s a masterclass in soft-focus photography that defined an entire era of French "Bilitis" style. For others? It’s a piece of evidence in a much darker conversation about the ethics of art.

Honestly, the legacy of David Hamilton is a mess. There’s no other way to put it.

What was The Age of Innocence actually about?

Released in 1995 (though Hamilton had been doing this for decades), the book is basically a collection of photographs featuring young girls—often in their early teens—captured in hazy, sun-drenched settings. Think French country houses, meadows, and wicker chairs. Everything is shot through that famous "Hamilton Blur."

He didn't just use a lens; he used a mood.

The images are accompanied by classical poetry. Pieces by Anne Frank, Algernon Charles Swinburne, and anonymous verses are peppered throughout the 214 pages. The goal was clearly to frame the work as a high-art exploration of "purity" and the fleeting transition from childhood to womanhood.

But here’s the thing: many of the girls are nude.

Hamilton’s wife at the time, Gertrude Versyp, actually co-designed the book. That’s a detail people often miss. It wasn't just some guy in a room; it was a curated, commercial product that sold millions of copies globally.

📖 Related: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

The "Hamilton Blur" and the 70s Aesthetic

If you’ve ever seen a photo from the 1970s that looks like someone smeared Vaseline on the lens, you're seeing the Hamilton influence. He was obsessed with backlighting and pastel tones.

- Technique: He often used soft-focus filters or even stretched stockings over the lens to get that dreamy, ethereal look.

- Lighting: Natural light was his best friend. He’d wait for that specific "golden hour" in St. Tropez.

- Composition: It wasn't about sharp lines. It was about textures—ruffled dresses, flowers, skin, and grain.

Basically, he wanted his photos to look like Impressionist paintings. He cited 19th-century Romanticism as a huge influence. You can see the Pre-Raphaelite vibes if you look closely enough at the poses. They’re deliberate. They’re theatrical.

Why the controversy didn't start (and then did)

Back in the day, Hamilton was a rockstar in the art world. He directed films like Bilitis (1977), which won awards. He was published in Vogue and Elle. In France, especially, nudity in art was—and often still is—viewed with a much more "laissez-faire" attitude than in the US or UK.

But the 90s changed everything.

When The Age of Innocence hit shelves, the climate was shifting. In 1998, a grand jury in Alabama actually indicted Barnes & Noble for selling the book, accusing them of distributing child pornography. They eventually dropped the charges, but the seal was broken.

You've got this massive clash of cultures. On one side, you have the "Art for Art's Sake" crowd who says the human form is beautiful and shouldn't be censored. On the other, you have people pointing out the power imbalance between a middle-aged photographer and a 13-year-old girl.

👉 See also: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

It's uncomfortable. It should be.

The tragic end of the story

The conversation around The Age of Innocence took a horrific turn in 2016. Flavie Flament, a well-known French TV host, published a book called La Consolation. In it, she alleged that a "famous photographer" had raped her when she was 13 during a shoot.

She later confirmed she was talking about David Hamilton.

After her story broke, several other former models came forward with similar accusations. Hamilton denied everything. He threatened to sue for defamation. But just a few days later, he was found dead in his Paris apartment. The cause was ruled a suicide by asphyxiation.

He was 83.

His death meant there would never be a trial. No cross-examinations. No legal closure for the women who accused him. It left the art world in a weird limbo. Can you still look at The Age of Innocence as art when the "innocence" part is now so heavily disputed by the subjects themselves?

✨ Don't miss: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

Is it still "art" in 2026?

That’s the million-dollar question. If you go to a gallery today, you likely won't see Hamilton's work on the walls. He’s been largely scrubbed from the mainstream "greats" list.

However, his technical influence is everywhere. Every "vintage" filter on Instagram owes a debt to his lighting. The "coquette" aesthetic on TikTok is basically a sanitized version of the Hamilton look. We’ve separated the style from the man, but the book remains a lightning rod.

In the UK, there were even legal warnings issued to book owners. In 2005, Surrey Police told people to destroy their Hamilton books or risk arrest. Later, they had to apologize because, legally, the books weren't actually banned. But the message was clear: the public’s stomach for this kind of work had turned.

Navigating the legacy

If you're a collector or an art historian, The Age of Innocence is a complicated artifact. It represents a time when the boundaries between "provocative art" and "exploitation" were incredibly blurry—much like the photos themselves.

Kinda makes you realize how much our "moral eye" has sharpened over the last few decades.

What was once seen as a poetic celebration of youth is now viewed through the lens of the "male gaze" and systemic abuse. You can't really look at those sun-drenched French fields the same way once you know what was happening behind the camera.

Actionable Insights for Art Enthusiasts

If you are researching this era of photography or come across these works, keep these points in mind for a balanced perspective:

- Contextualize the Era: Understand that the 1970s had a vastly different legal and social framework regarding youth and nudity. It doesn't excuse the behavior, but it explains why it was allowed to flourish.

- Separate Style from Subject: You can appreciate soft-focus techniques or 70s color palettes without endorsing the specific subject matter Hamilton chose. Look into photographers like Sarah Moon or Lillian Bassman for similar dreamlike aesthetics without the same ethical baggage.

- Listen to the Models: When evaluating "innocence" in art, the most important voices are the ones in the frame. Reading Flavie Flament’s account provides a necessary counter-narrative to Hamilton’s "purity" claims.

- Legal Awareness: Be aware that while "art books" are generally protected, certain jurisdictions have very specific laws regarding the possession of images of minors. Always check local regulations if you are collecting vintage art monographs.