You’ve probably spent years looking at a lie. It’s hanging on the wall of almost every classroom in the world. It’s on the news. It’s on your favorite weather app. Most of us grew up thinking Greenland is roughly the same size as Africa and that Europe is a massive landmass dominating the center of the world.

It’s not.

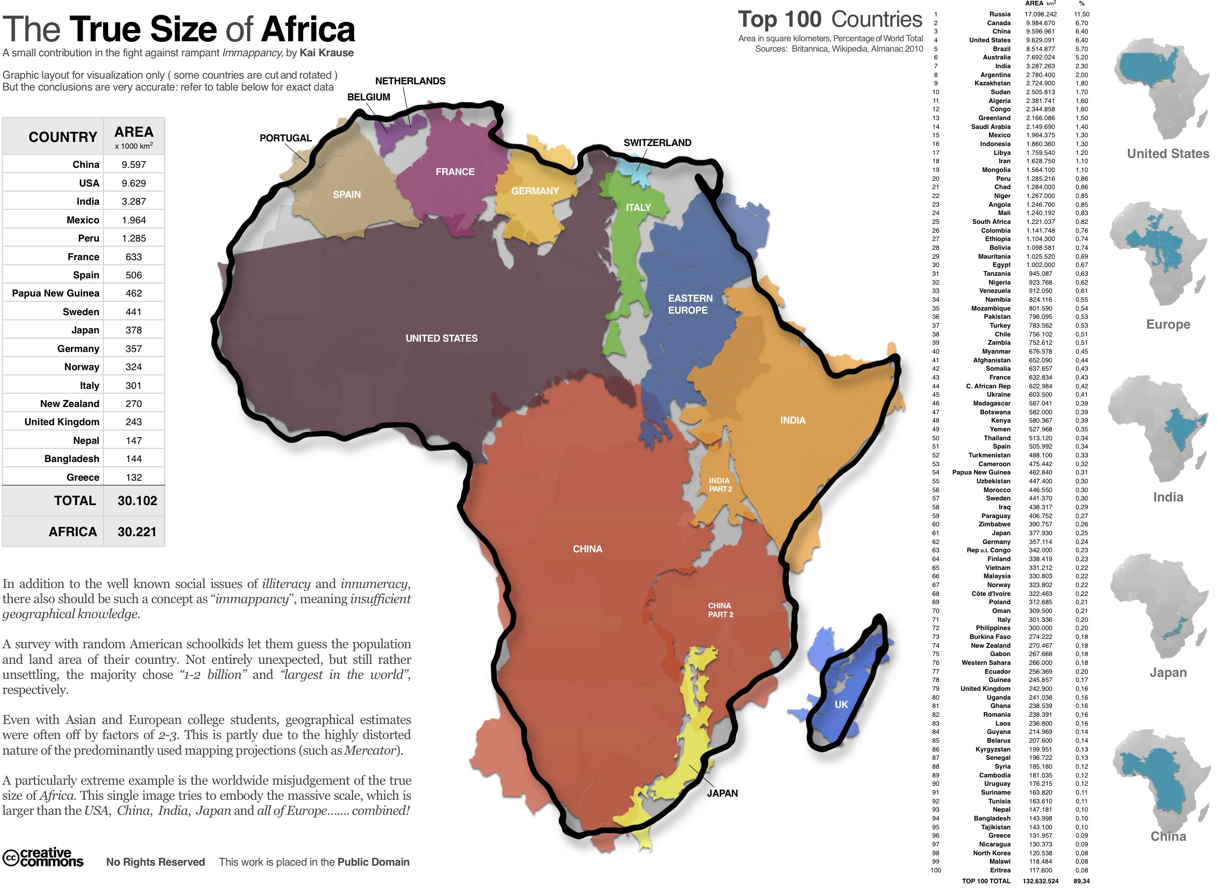

When you look at an africa actual size map, the reality is a bit of a gut punch. Greenland is actually fourteen times smaller than Africa. Fourteen. You could fit the entire United States, China, India, and most of Europe inside the borders of the African continent, and you’d still have room left over for a few extra countries.

Geography is weird. Maps are math, and math doesn't always play nice with a round planet.

The Mercator Problem and Why We’re All Confused

So, why did everyone lie to us? Honestly, it wasn't a conspiracy. It was a navigation hack. Back in 1569, a cartographer named Gerardus Mercator created a map to help sailors cross the ocean. To make sure a ship's compass bearing stayed a straight line on paper, he had to stretch the globe.

Think about an orange peel. If you try to flatten it out on a table, it rips. To make it a perfect rectangle, you have to stretch the top and bottom until they match the width of the middle.

This distortion is why countries far from the equator look gigantic. Since Africa sits right on the equator, it barely gets stretched at all. Meanwhile, places like Canada, Russia, and Sweden look like they’re taking over the world. We’ve been conditioned to equate physical size on a map with geopolitical importance, which is why the africa actual size map feels so jarring when you first see it.

It's basically a massive optical illusion that stayed in style for 450 years too long.

🔗 Read more: Anime Pink Window -AI: Why We Are All Obsessing Over This Specific Aesthetic Right Now

Kai Krause and the Infographic That Changed Everything

In the early 2010s, a computer graphics expert named Kai Krause released a visualization that went viral before "going viral" was even a thing. He didn't just tell people Africa was big; he showed them.

He took the outlines of the world's major powers and physically pasted them inside the outline of Africa.

The results were staggering:

- The United States fits comfortably into the northern chunk.

- China slides right into the eastern side.

- India takes up the southern tip.

- Western Europe (the UK, France, Germany, Spain, Italy) fills in the remaining gaps like Tetris blocks.

Krause called this "Immappancy"—the cartographic equivalent of illiteracy. We literally don't know what our own world looks like.

The Numbers Don't Lie

Africa covers about 30.3 million square kilometers.

That number is hard to wrap your head around, so let's put it in perspective. The United States is roughly 9.8 million square kilometers. China is about 9.6 million. You could drop both of those massive nations into Africa and still have over 10 million square kilometers of land left over. That's a whole extra Europe.

Most people don't realize that the distance from London to Cairo is shorter than the distance from Cairo to Cape Town. Africa is long. It's wide. It’s roughly 5,000 miles from north to south.

If you’re flying from New York to Singapore, you realize the world is big. But if you're flying from Dakar in the west to Djibouti in the east, you’re covering a distance that would take you across the entire Atlantic Ocean.

💡 You might also like: Act Like an Angel Dress Like Crazy: The Secret Psychology of High-Contrast Style

Gall-Peters and the Battle for the "True" Map

Because the Mercator projection is so skewed, some people have pushed for the Gall-Peters projection. You might remember this from a famous episode of The West Wing. It’s an "equal-area" map. It shows the sizes of continents accurately, but it distorts their shapes.

Africa looks like a long, stretched-out piece of taffy on a Gall-Peters map. It’s ugly. It’s hard to look at because we’re so used to the "classic" shapes. But it’s much closer to the truth regarding landmass.

Then you have the Robinson projection, which tries to find a middle ground. It distorts both size and shape a little bit so that nothing looks too crazy. Most National Geographic maps use something like this. But even then, the africa actual size map still surprises people because our brains are stubborn. We want to believe the first thing we learned in third grade.

Why This Matters for More Than Just Geography

This isn't just about trivia or winning a bar bet. The way we perceive the world's size affects how we perceive its value.

When Africa is shrunk on a map, it’s easier for people in the "Global North" to dismiss it as a single, homogenous entity. You hear people say they are "going to Africa" as if it’s a weekend trip to a small country.

Africa is a massive continent with 54 distinct nations, thousands of languages, and incredibly diverse climates. You can’t "see Africa" in a week. You can barely see a corner of it. Understanding the actual size of Africa helps us appreciate the sheer scale of the logistical, political, and social diversity there.

Think about infrastructure. If you’re trying to build a railway across a continent that is three times the size of Europe, the cost and effort are on a completely different level. When we use the wrong maps, we set the wrong expectations.

📖 Related: 61 Fahrenheit to Celsius: Why This Specific Number Matters More Than You Think

Digital Maps Are Solving (and Creating) Problems

Google Maps and Apple Maps have mostly moved toward a 3D globe view when you zoom out far enough. This is great! It finally shows the africa actual size map in its true glory. When you spin that digital globe, you see just how much of the planet Africa occupies.

However, the second you zoom in and the screen becomes 2D, the Mercator distortion kicks back in. Why? Because you need those 90-degree street corners to look like 90-degree street corners. If Google Maps used a different projection for city streets, every building would look like a tilted parallelogram.

So, we’re stuck with a hybrid reality. We use the "wrong" map for navigation because it's practical, but we need the "right" map for perspective.

What You Should Do Next

If you want to actually "see" the world correctly, stop looking at flat posters.

- Get a Globe: It sounds old school, but a physical globe is the only way to see the true relationship between landmasses without a computer algorithm distorting things.

- Use The True Size Tool: There’s a fantastic website called thetruesize.com. You can type in any country and drag it over Africa. Dragging Russia or Canada toward the equator is a humbling experience. They shrink right before your eyes.

- Check Out AuthaGraph: If you want to see the most accurate flat map ever made, look up the AuthaGraph World Map. It was created by Japanese architect Hajime Narukawa. It manages to represent all landmasses and oceans accurately by folding the world into a tetrahedron before flattening it. It looks weird, but it's arguably the "truest" map we have.

Basically, the next time you see a map where Africa looks comparable in size to Greenland, just remember: you're looking at a 16th-century navigational tool, not a portrait of our planet. Africa is gargantuan. It’s time we started looking at it that way.

To truly understand the scale of the world, start comparing countries by their square mileage rather than their visual representation. When you see that Algeria alone is larger than the entire state of Alaska, or that the Democratic Republic of the Congo is roughly the size of Western Europe combined, the "actual size" of the continent begins to click. Use interactive digital globes for any geographical planning or educational sessions to avoid reinforcing the Mercator bias that has dominated Western education for centuries.