You’ve been staring at a lie since kindergarten.

That colorful poster on your classroom wall? It’s wrong. Greenland isn’t the size of Africa. Not even close. In reality, Africa is about 14 times larger than Greenland. But looking at a standard Mercator projection, you’d swear they were twins. This isn't just a minor "oops" in printing—it’s a fundamental mathematical problem that has shaped how we see the world for centuries. When we talk about an actual scale world map, we’re usually trying to fix a puzzle that is, quite literally, impossible to solve perfectly.

The earth is a sphere. Or, if you want to be a nerd about it, an oblate spheroid. Maps are flat. You can't flatten a sphere without stretching it, tearing it, or squishing the life out of it. Think about peeling an orange and trying to press the peel perfectly flat against a table. It’s going to rip. To fill those rips, mapmakers stretch the image.

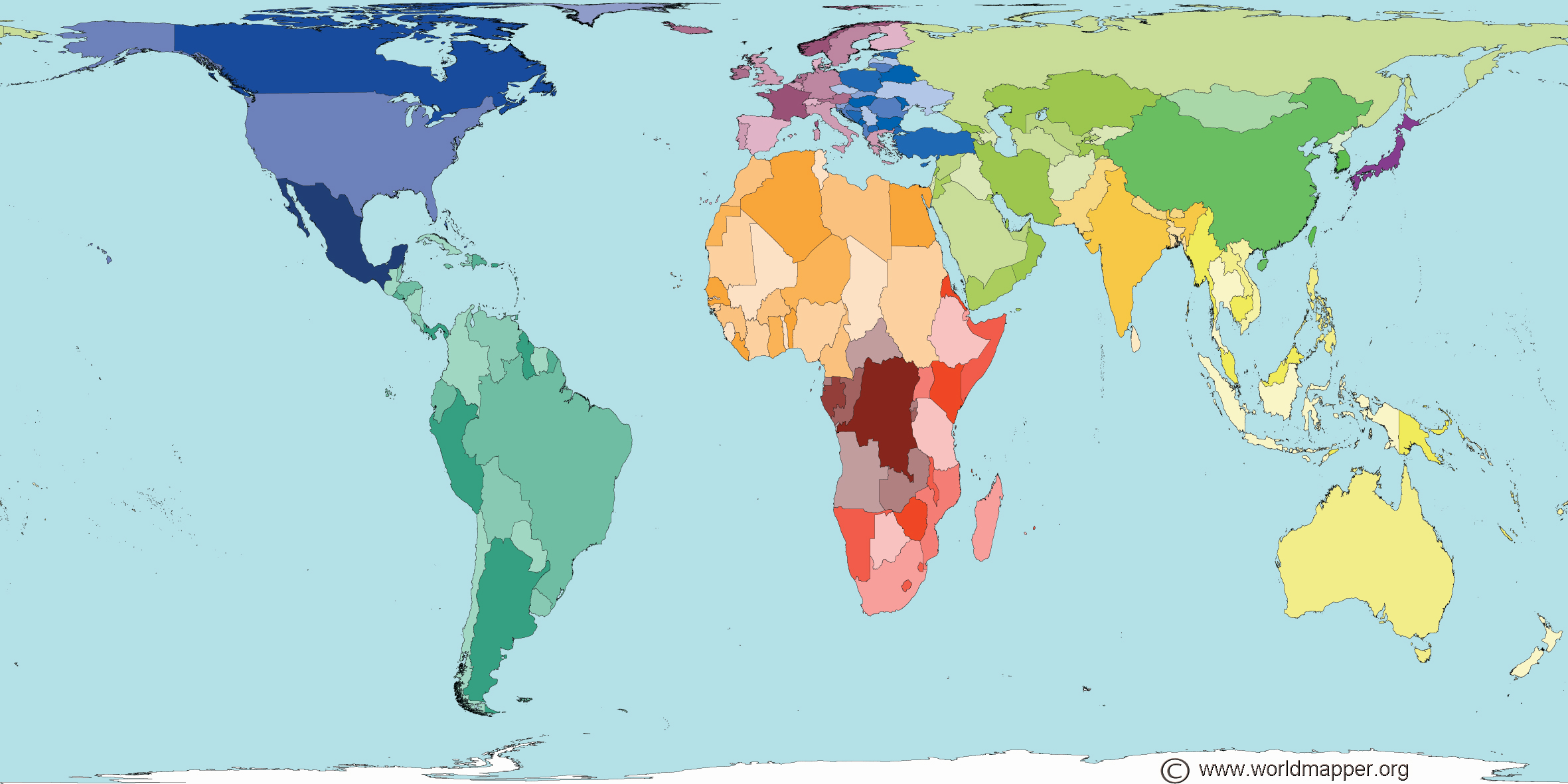

The result? A massive distortion that makes Europe and North America look huge while the Global South shrinks.

The Mercator Problem and Why It Stuck

Gerardus Mercator created his famous map in 1569. He wasn't trying to trick you. He was trying to help sailors. Because his map preserved constant bearings—meaning a straight line on the map was a straight line on a compass—it became the gold standard for navigation. If you were a 16th-century captain crossing the Atlantic, Mercator was your best friend.

But for everyone else? It’s a mess.

The Mercator projection uses a mathematical formula where the scale increases as you move away from the equator. Greenland looks like a continent. Antarctica looks like a never-ending ice wall. Meanwhile, Brazil is actually larger than the contiguous United States, but on a Mercator map, it looks like a small fraction of it.

👉 See also: Why VidMate Old Version 2013 Still Matters to Android Purists

Honestly, it messes with our heads. When we see some countries as "bigger," we subconsciously attribute more power or importance to them. This isn't just some conspiracy theory; it’s a documented psychological effect called "map bias."

Searching for the Actual Scale World Map

If you’re looking for a map that shows things as they really are, you’re looking for an "equal-area" projection. These maps prioritize the actual surface area of landmasses over the shape or the direction.

One of the most famous attempts to fix this is the Gall-Peters projection. It’s the one you might have seen in that famous West Wing episode. It shows the relative sizes of continents accurately, but it makes them look "stretched" vertically. Africa looks like a long, thin teardrop. It’s jarring. People hate it because it looks "ugly," but it’s technically more honest about size than the maps we grew up with.

Then there is the AuthaGraph. Created by Japanese architect Hajime Narukawa in 1999, this is probably the closest thing we have to a perfect actual scale world map. Narukawa divided the globe into 96 triangles, projected them onto a tetrahedron, and then unfolded it into a rectangle.

It’s brilliant.

The AuthaGraph preserves the area of oceans and continents while minimizing the weird stretching you see in other maps. It even lets you tile the map infinitely. It won the Good Design Grand Award in Japan, and for good reason—it actually shows how isolated Antarctica is and how massive the Pacific Ocean truly feels.

✨ Don't miss: The Truth About How to Get Into Private TikToks Without Getting Banned

The Tech Behind Modern Accuracy

We don’t just rely on 16th-century math anymore.

Today, we have the World Geodetic System (WGS 84). This is the "map" that lives inside your phone. Every time you open Google Maps or use GPS, you’re using a coordinate system tied to the Earth's center of mass.

However, even Google Maps uses a version of Mercator for its 2D view. Why? Because it preserves angles. If you’re walking down a street and turn 90 degrees, you want the map to show a 90-degree turn. If Google used an equal-area projection for city navigation, the buildings and streets would look skewed and distorted as you scrolled.

Why Scale Matters for Business and Climate

This isn't just for geography buffs. Scale matters for real-world logistics.

- Shipping Routes: If you rely on a distorted map, you’ll fundamentally misunderstand the distance of the "Great Circle" routes that planes and ships actually take.

- Climate Change: When we look at the melting of the Arctic or Antarctic, scale is vital. If the map makes the poles look five times bigger than they are, our visual perception of ice loss is skewed.

- Resource Management: Africa has more landmass than the US, China, India, Japan, and most of Europe combined. When businesses look at "emerging markets," they often underestimate the sheer physical scale of the African continent because of the maps they use in boardrooms.

Comparing the Reality

Let’s look at some real numbers that prove how much the "standard" map lies to us.

Russia is the largest country on Earth. It’s roughly 17 million square kilometers. On a Mercator map, it looks larger than Africa. But Africa is 30 million square kilometers. Russia is barely more than half its size.

🔗 Read more: Why Doppler 12 Weather Radar Is Still the Backbone of Local Storm Tracking

Similarly, look at Australia. On a standard map, it looks comparable to a large island like Greenland. In reality, you could fit Greenland into Australia nearly three and a half times.

It's wild.

Moving Toward a Better View

So, what should you actually use if you want to see the world "correctly"?

There is no single perfect map, but the Robinson projection is a good compromise. It doesn't get the area or the shapes perfectly right, but it "distorts everything a little bit" to make the whole thing look more natural to the human eye. It was used by National Geographic for years because it just felt "right."

But if you want the truth? Use a globe.

A physical globe is the only way to see the actual scale world map without a computer program doing some heavy lifting. If you can't carry a globe in your pocket, digital tools like "The True Size Of" allow you to drag countries around and see how they shrink or grow based on latitude. Dragging the UK over to the equator is a humbling experience for anyone who thinks Europe is huge.

Actionable Steps for Accurate Geographic Understanding

- Audit your visual bias: Use the The True Size Of tool to manually compare your home country to others. Drag it to the equator to see its "un-stretched" size.

- Switch your projection: If you are a teacher, researcher, or designer, stop using Mercator for data visualization. Use the Mollweide or Eckert IV projections for any map where you are comparing quantities (like population or CO2 emissions) between regions.

- Think in 3D: When planning long-distance travel or logistics, use Google Earth’s 3D globe view rather than the 2D map. It uses the WGS 84 ellipsoid to provide the most mathematically accurate representation of distance over a curved surface.

- Challenge the "Top-Down" view: Remember that "North is up" is a social convention, not a physical law. Looking at a "South-up" map can help break the mental hierarchy created by 500 years of Eurocentric mapmaking.