You've probably heard it without even realizing what it was. It’s that specific, rhythmic "click" at the end of a stanza that makes a poem feel like it just landed perfectly on its feet. We are talking about the ababcc rhyme scheme. It's a six-line structure, often called a sestet, and it’s basically the secret weapon of some of the greatest writers in history.

Why? Because it builds tension and then lets it go.

Most people are used to the simple back-and-forth of a standard quatrain, like the $abab$ pattern you see in common hymns or folk songs. But when you tack that $cc$ couplet onto the end, everything changes. It’s like a musical resolution. You have the alternating rhyme that feels like a conversation, and then—bam—a rhyming pair that acts like a definitive period at the end of a sentence.

What is the ABABCC rhyme scheme anyway?

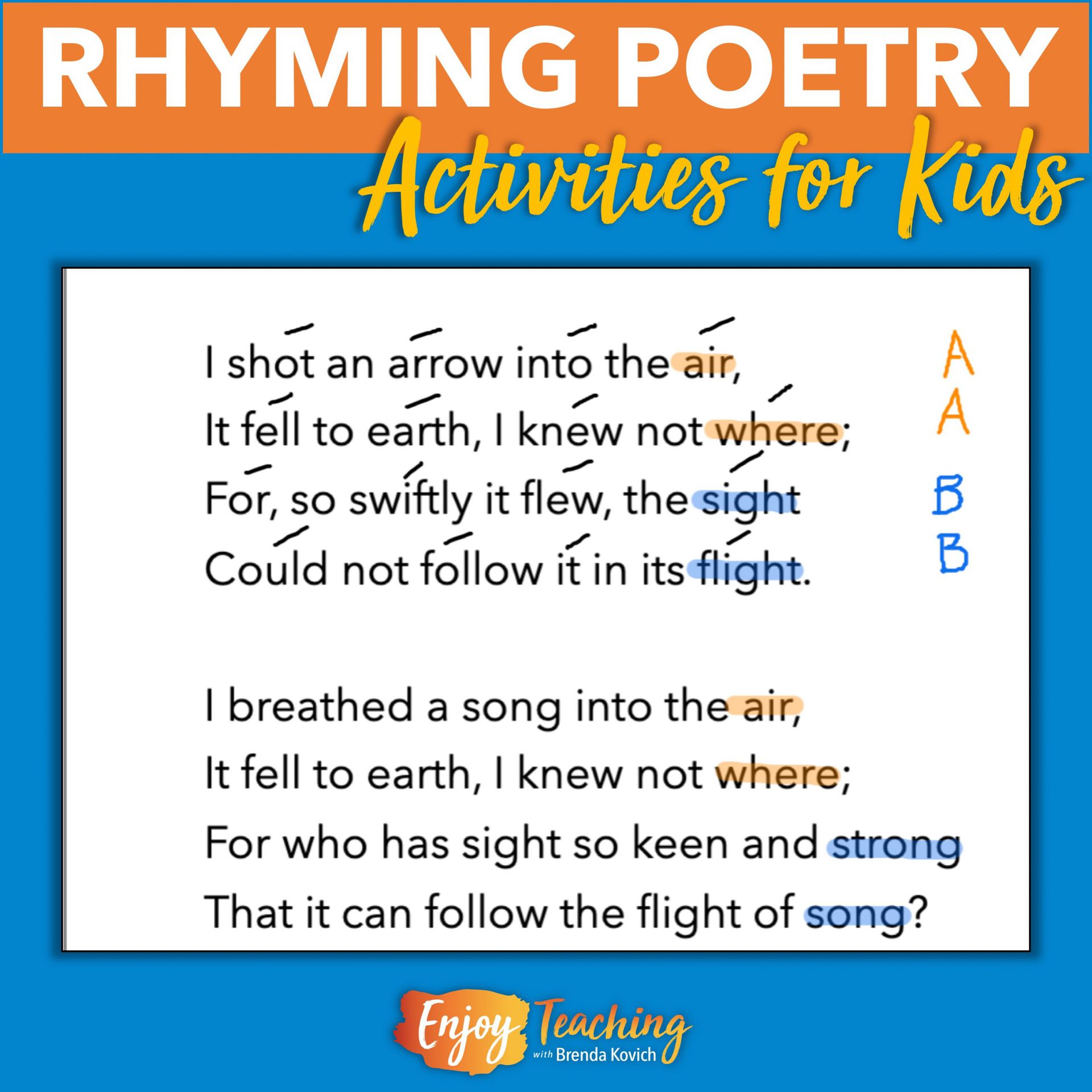

Let’s keep it simple. In this pattern, the first line rhymes with the third (that's your $a$). The second line rhymes with the fourth ($b$). Then, the final two lines rhyme with each other ($c$).

It looks like this:

- Line 1 (a)

- Line 2 (b)

- Line 3 (a)

- Line 4 (b)

- Line 5 (c)

- Line 6 (c)

Poets love this because it offers more room to breathe than a four-line stanza but isn't as intimidating or rigid as a full fourteen-line sonnet. It’s the "Goldilocks" of poetic structures. Just right.

The Venus and Adonis connection

If you want to sound smart at a dinner party, call this the "Sestet of Venus and Adonis." Why? Because William Shakespeare used it for his famous narrative poem Venus and Adonis.

👉 See also: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

"Even as the sun with purple-colour'd face

Had ta'en his last leave of the weeping morn,

Rose-cheek'd Adonis hied him to the chase;

Hunting he lov'd, but love he laugh'd to scorn;

Sick-thoughted Venus makes amain unto him,

And like a bold-fac'd suitor 'gins to woo him."

See how that works? Face and chase are the $a$ rhymes. Morn and scorn are the $b$ rhymes. Then Shakespeare hits you with the $cc$ punchline: unto him and woo him. It’s snappy. It feels complete. Honestly, it’s one of the reasons this specific poem became a massive "bestseller" in the 1590s. People just liked the way it sounded.

Wordsworth and the lonely cloud

You can’t talk about the ababcc rhyme scheme without mentioning William Wordsworth. His poem "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud" (you know, the one about the daffodils) is the poster child for this structure.

Think about the rhythm.

"I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o'er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze."

The $abab$ section sets the scene—the cloud, the hills, the crowd, the daffodils. It’s descriptive and fluid. But then the $cc$ couplet—trees and breeze—locks the image in place. It gives the reader a sense of peace. Wordsworth wasn't just picking rhymes out of a hat; he used the structure to mimic the steady, repetitive motion of flowers swaying in the wind.

Why this pattern still works for modern writers

Poetry can feel kinda dusty sometimes. I get it. But the logic behind the ababcc rhyme scheme is actually the same logic used in modern songwriting and even stand-up comedy.

✨ Don't miss: Shamea Morton and the Real Housewives of Atlanta: What Really Happened to Her Peach

Think about a joke. You have the setup (the $abab$ part where you establish the context) and then the punchline (the $cc$ part where the twist happens). In a song, the couplet at the end of a verse often acts as a "turn" that leads you into the chorus. It’s a psychological trick. Our brains crave patterns, but we also crave the end of patterns. The couplet provides that "aha!" moment.

Breaking down the mechanics

If you’re trying to write one of these yourself, the biggest mistake is making the $cc$ rhyme feel forced. In a good sestet, the couplet shouldn't just be there to rhyme; it should summarize the previous four lines or offer a new perspective on them.

Some poets use the $abab$ section to ask a question and the $cc$ section to answer it. Others use the first four lines to describe a physical object and the last two to describe an emotion. There's a lot of flexibility here.

Common variations and cousins

- The Rime Royal: This is a seven-line giant ($ababbcc$). It’s basically the $ababcc$ pattern with an extra $b$ rhyme shoved in the middle. Geoffrey Chaucer was obsessed with it.

- The Heroic Couplet: This is just the $cc$ part, repeated forever. It’s much more driving and relentless than the balanced feel of the six-line sestet.

- The Common Meter: This is usually just $abab$. It’s simpler, sure, but it lacks that final "tuck-in" feeling that the extra couplet provides.

The technical side of the "Sestet"

When we look at the ababcc rhyme scheme from a technical standpoint, we have to look at meter. Most of the famous examples are written in iambic pentameter—that "da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM" heartbeat rhythm.

When you combine iambic pentameter with this rhyme scheme, you get a very formal, "important" sounding poem. However, if you switch it up to iambic tetrameter (four beats per line instead of five), the poem starts to feel more like a nursery rhyme or a lighthearted song. Wordsworth used tetrameter for his daffodils, which is why it feels so airy and light. Shakespeare used pentameter for Venus and Adonis, which gave it a more serious, epic quality.

Notable examples you should actually read

If you want to see how the masters handled this, don’t just take my word for it. Check these out:

🔗 Read more: Who is Really in the Enola Holmes 2 Cast? A Look at the Faces Behind the Mystery

- "The Character of a Happy Life" by Sir Henry Wotton. This is a masterclass in using the scheme to provide moral advice. The couplets feel like proverbs.

- "She Walks in Beauty" by Lord Byron. While not a perfect $ababcc$ throughout (he mixes it up), you can see the influence of the six-line structure in how he balances his descriptions of light and dark.

- "The Garden of Love" by William Blake. Blake is the king of making simple structures feel incredibly eerie and profound.

Practical tips for using ABABCC in your own work

Ready to try it? Don't overthink it.

Start with a simple observation in the first four lines. If you're writing about a rainy day, use the $a$ and $b$ lines to talk about the sound of the water or the color of the sky. Then, use the final $cc$ couplet to reveal how the rain makes you feel—maybe you're cozy, or maybe you're lonely.

Watch your syllable counts. If your $a$ lines have ten syllables and your $c$ lines have four, the poem is going to feel like it’s tripping over its own feet. Try to keep the line lengths relatively consistent unless you’re intentionally trying to make the reader feel uneasy.

Don't use "easy" rhymes. "Cat" and "hat" are fine for Dr. Seuss, but if you want your poem to have weight, try slant rhymes (like "bridge" and "grudge") or more complex multisyllabic rhymes.

Actionable insights for poets and students

To truly master the ababcc rhyme scheme, stop looking at it as a set of rules and start looking at it as a container for your thoughts.

- Analyze the "Turn": Look at the transition between line 4 and line 5. In the best poems, there is a "volta" or a turn here. The mood shifts slightly.

- Read Aloud: This specific scheme is designed for the ear, not just the eye. If the couplet at the end doesn't feel satisfying when spoken, it probably needs a rewrite.

- Experiment with Meter: Try writing one in a fast meter (like anapestic) and see how it changes the "vibe" of the $cc$ couplet. It usually makes it sound more comedic.

- Identify the Narrative Arc: Use the $abab$ to set the scene and the $cc$ to deliver the "so what?" of the poem.

Whether you are studying for an English lit exam or trying to write a heartfelt card for someone, understanding this pattern gives you a direct line to how some of the most beautiful English verse was constructed. It’s a tool. Use it to create resonance.

Once you start seeing the $ababcc$ pattern, you’ll see it everywhere. It’s in the lyrics of classic rock songs and the structure of modern "Instapoetry." It’s timeless because the human brain is hardwired to appreciate the balance of a shifting pattern followed by a solid, rhyming resolution.

Next Steps for Mastery

- Scan a Poem: Take Wordsworth’s "Daffodils" and mark the $a$, $b$, and $c$ lines. Note where the poet changes the subject matter between the quatrain and the couplet.

- Write a Practice Sestet: Pick a mundane object—like a coffee mug or a laptop—and write exactly six lines following the ababcc rhyme scheme. Focus on making the final two lines feel like a "conclusion" to the first four.

- Compare Structures: Read a poem in $abab$ (Common Meter) and then read a sestet. Notice how the sestet feels more "grounded" because of those two extra lines at the end.