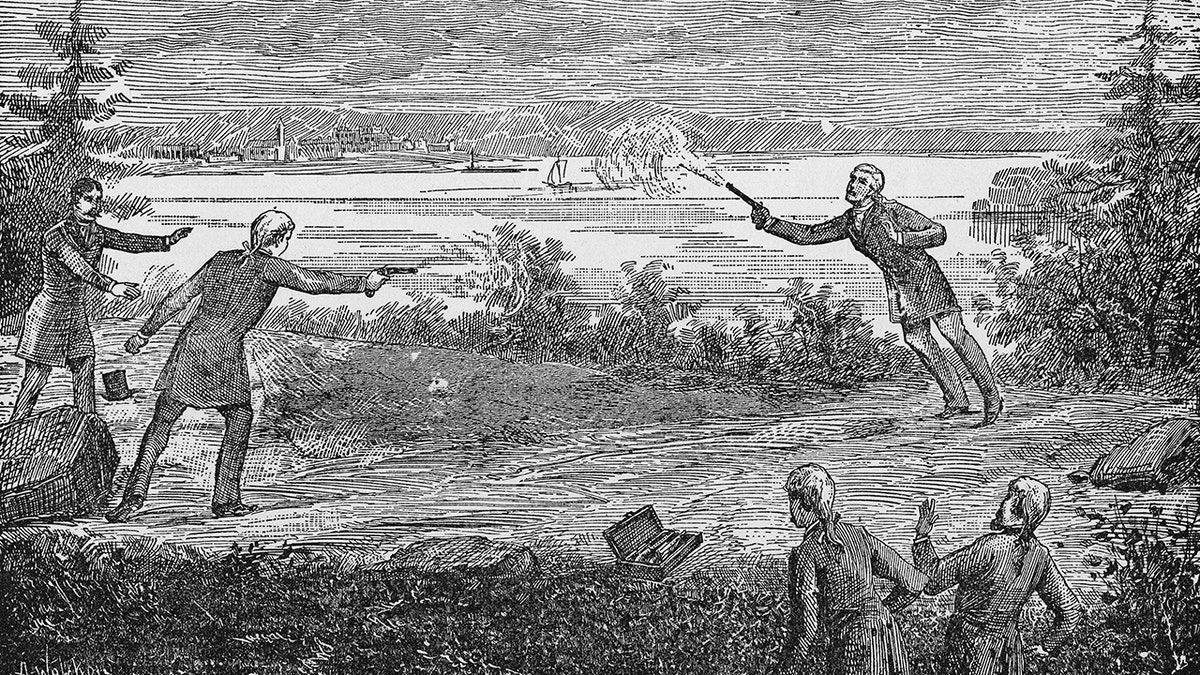

Alexander Hamilton was dead. The morning of July 11, 1804, changed everything. One shot from a .54 caliber Wogdon & Barton pistol didn't just end the life of the first Treasury Secretary; it effectively ended the political career of the sitting Vice President of the United States.

People think they know the story because of the Broadway musical or high school history books. They think Burr just sort of faded away into the shadows of New Jersey or lived out a quiet, shameful exile. That’s not even close to the truth. What happened to Aaron Burr after he killed Hamilton was a chaotic, decade-long spiral involving murder warrants, a secret army, an alleged attempt to steal half of North America, and a final act as a disgraced lawyer in New York.

He didn't just walk away. He ran.

The Immediate Fallout: A Vice President on the Lam

Burr returned to Manhattan after the duel and ate breakfast. Seriously. He sat down for a meal like he hadn't just mortally wounded one of the founding fathers. But the "code duello" of the 1800s was a fickle thing. While dueling was common, killing a man as prominent as Hamilton—who took over 30 hours to die in agony—was a PR nightmare.

By the time Hamilton’s body was cold, Burr was a wanted man. He was eventually indicted for murder in both New York and New Jersey. Imagine that for a second. The sitting Vice President was a fugitive.

He fled south. Burr basically spent the next few months hiding in Georgia and South Carolina, staying with old revolutionary war buddies and trying to wait for the heat to die down. It’s wild to think about, but he actually returned to Washington D.C. to finish his term as Vice President. He presided over the impeachment trial of Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase while there were still active warrants for his arrest.

Politics was weird back then.

The Western Conspiracy: Did Burr Try to Start His Own Country?

Once his term ended in 1805, Burr was broke and politically toxic. He couldn't go back to New York law practice, and Thomas Jefferson hated his guts. So, Burr did what any disgraced 19th-century politician would do: he headed West.

💡 You might also like: Robert Hanssen: What Most People Get Wrong About the FBI's Most Damaging Spy

This is where things get truly bizarre. This is the "Burr Conspiracy" phase.

Burr began communicating with General James Wilkinson—who, it turns out, was a double agent for Spain—about a vague plan involving the Louisiana Purchase territories and Mexico. Historians like Nancy Isenberg, who wrote American Sphinx, still debate what Burr was actually trying to do. Was he planning to invade Spanish-held Mexico to "liberate" it? Or was he actually trying to get the Western states to secede from the Union and crown him as a sort of Emperor of the West?

He started recruiting men. He bought 40,000 acres of land in the Washita River valley. He was building boats.

Jefferson eventually got wind of it. In 1807, the President issued a proclamation for Burr’s arrest, accusing him of treason. Burr tried to flee to Spanish Florida disguised in a floppy hat and old clothes, but he was caught in Alabama.

The Trial of the Century (Before the 20th Century)

The treason trial in Richmond, Virginia, was a circus. It was the O.J. Simpson trial of the 1800s. Chief Justice John Marshall presided, and the tension was thick because Marshall and Jefferson loathed each other.

The prosecution had a problem: the Constitution has a very specific, very narrow definition of treason. You need two witnesses to an "overt act" of war against the United States. Burr was a brilliant lawyer; he knew the law better than the people prosecuting him.

He was acquitted.

📖 Related: Why the Recent Snowfall Western New York State Emergency Was Different

The jury basically said there wasn't enough evidence of a physical act of war, even if his intent was shady. But even though he was legally a free man, the public saw him as a traitor. He was burned in effigy in cities across the country. He was the most hated man in America.

Four Years of European Exile

Burr realized he had no future in the States for a while. In 1808, he used an alias—"H.E. Edwards"—and slipped onto a ship headed for England.

His life in Europe was a mix of high-society flirting and desperate poverty. He hopped from London to Sweden, then Germany and France. He was constantly trying to pitch "The Burr Plan" to anyone who would listen, including Napoleon Bonaparte. He wanted backing for an invasion of Mexico. Napoleon, understandably busy with his own wars, ignored him.

Burr eventually ran out of money. There are letters from this period where he talks about being so poor he couldn't afford a fire in his room during a Swedish winter. He was essentially a wandering ghost of the American Revolution.

The Return and the Final Tragedy

In 1812, Burr finally sneaked back into New York. He used a wig and a fake name to avoid his creditors. Eventually, he realized the government wasn't interested in hanging him anymore, so he opened a small law office.

He actually did okay for a while. He was still a sharp legal mind. But his personal life was a wreck.

His daughter, Theodosia Burr Alston, was the light of his life. In 1813, she boarded a ship called the Patriot to come visit him in New York. The ship vanished. It was never found. Most people assume it went down in a storm off Cape Hatteras, but there were rumors of pirates for decades. Burr was devastated. He used to walk the Battery in Manhattan every day, looking out at the ocean, hoping she’d magically appear.

👉 See also: Nate Silver Trump Approval Rating: Why the 2026 Numbers Look So Different

The Final Marriage Scandal

Even in his 70s, Burr couldn't stay out of trouble. In 1833, he married Eliza Jumel, a wealthy and somewhat notorious widow. She was arguably the richest woman in America.

It didn't last.

Burr immediately started blowing her money on bad land speculations—the same kind of stuff that got him into trouble in the West decades earlier. Within four months, they separated. Eliza hired a lawyer to divorce him.

The lawyer she hired? Alexander Hamilton Jr.

You can't make this stuff up. The son of the man Burr killed was the one who finally stripped him of his last bit of wealth and dignity. The divorce was finalized on the very day Aaron Burr died: September 14, 1836.

Lessons from the Burr Legacy

When we look at what happened to Aaron Burr after he killed Hamilton, we see a man who was a brilliant architect of his own destruction. He was a visionary who lacked a moral compass, or perhaps just a man who didn't understand that the era of "gentlemanly" politics had shifted into something more populist and unforgiving.

If you want to understand the real history of the early U.S., you have to look past the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. Burr represented a third way—a raw, opportunistic ambition that the young country wasn't ready for.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

- Visit the Morris-Jumel Mansion: If you’re in New York, you can visit the house where Burr lived during his brief, disastrous final marriage. It’s the oldest house in Manhattan and still feels like the 1830s.

- Read the Trial Transcripts: The Burr treason trial is a masterclass in constitutional law. If you’re a law student or a history nerd, looking at how John Marshall defined treason is essential.

- Trace the Western Route: Burr’s "empire" was centered around Blennerhassett Island in West Virginia. It’s now a state park you can visit to see exactly where he staged his "conspiracy."

Burr didn't leave a legacy of great laws or institutions. He left a legacy of "what ifs." He died alone in a boarding house, a reminder that in American politics, winning a duel is often the fastest way to lose the war.

Next Steps for Further Research

To get the most accurate picture of Burr's complex life, consult the "Papers of Aaron Burr" edited by Mary-Jo Kline. For a modern take on his political philosophy, Ron Chernow’s Hamilton provides the perfect counter-narrative, while Nancy Isenberg’s Fallen Founder offers the most sympathetic, deeply researched look at Burr's actual motivations during his Western expeditions.