February 1943 was a total mess for the Wehrmacht. After the disaster at Stalingrad, the entire southern wing of the German front wasn't just leaking; it was basically dissolving. The Red Army was surging forward, fueled by the massive momentum of Operation Liberty, looking to trap everything from the Don River to the Caucasus. Most people think the war was decided at Stalingrad or Kursk, but the 3rd battle of Kharkov is where the Eastern Front actually took its most bizarre, counter-intuitive turn.

It was freezing. Men were exhausted. The Soviet high command, the Stavka, thought they were about to win the whole thing right then and there. They were wrong.

The overextension trap nobody saw coming

The Soviet advance was fast. Maybe too fast. General Nikolai Vatutin and his Voronezh Front were pushing toward the Dnieper River, fueled by the adrenaline of chasing a retreating enemy. They had taken Kharkov, a massive industrial hub, and were eyeing the crossings that would cut off the Germans in the south. Honestly, from a map view, it looked like a total collapse of the German lines.

But distance is a killer in Russia.

By the time the Soviets reached the outskirts of the Dnieper, their supply lines were stretched over hundreds of miles of snowy, rutted roads. Tanks were running out of fuel. Soldiers hadn't had a hot meal in days. More importantly, their "teeth" were dull—tank brigades that started with 100 vehicles were down to 10 or 15. This is the context you need to understand the 3rd battle of Kharkov. It wasn't just about tactical genius; it was about the brutal physics of logistics.

Erich von Manstein, arguably the most competent commander the Germans had, saw this thinning of the Soviet spearhead. He did something incredibly ballsy. While Hitler was screaming for every inch of ground to be held—literally demanding "fortress" cities—Manstein convinced him to let the Germans retreat further. He wanted the Soviets to keep coming. He wanted them to get even more overextended.

✨ Don't miss: Melissa Calhoun Satellite High Teacher Dismissal: What Really Happened

Manstein’s "Backhand Blow" explained (simply)

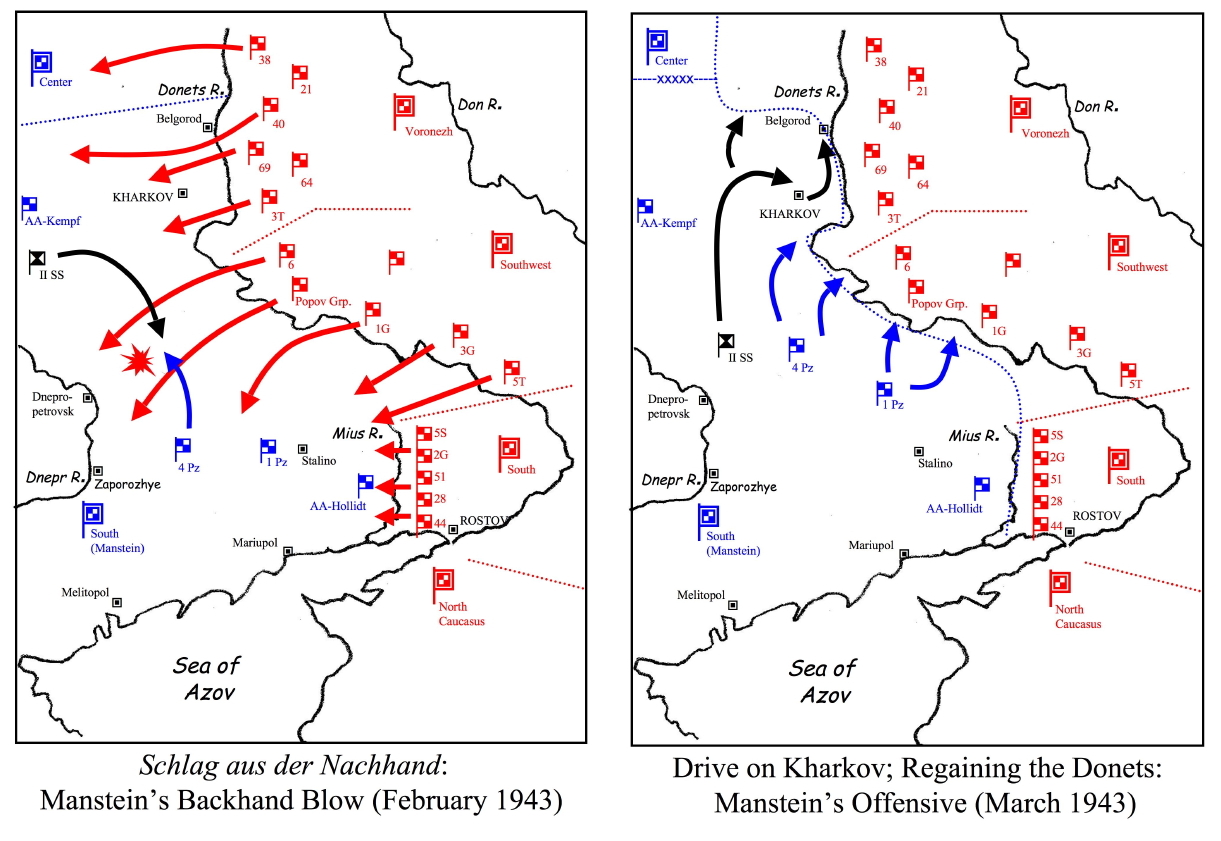

This is the famous Schlagen aus der Hinterhand. Most history books make it sound like a chess move, but on the ground, it was more like a desperate street fight. Manstein gathered the remnants of the 4th Panzer Army and the newly formed II SS Panzer Corps. These weren't just any units; they had the new Tiger tanks. While they weren't perfect, they were terrifyingly effective in 1943.

The German plan was basically a giant pincer move against the overstretched Soviet flank. Instead of hitting the head of the Soviet spear, they slammed into the sides.

On February 20th, the counteroffensive kicked off. The weather was a nightmare. Thaws turned roads into "rasputitsa" mud, then they froze back into iron-hard ruts. The German tanks moved anyway. They caught the Soviet 6th Army and the "Popov Group" completely off guard. These Soviet units were so focused on moving forward that they didn't even realize their flanks had evaporated until German shells started landing in their rear command posts.

It was a slaughter.

The 3rd battle of Kharkov showed that a mobile defense could work, even against a numerically superior foe. Within days, the Soviet advance didn't just stop; it disintegrated. The Germans recaptured the city of Kharkov by mid-March, but it wasn't a clean victory. The fighting inside the city was house-to-house, brutal, and frankly, unnecessary according to some later historians who argued Manstein should have just bypassed the urban center.

🔗 Read more: Wisconsin Judicial Elections 2025: Why This Race Broke Every Record

Why the Soviet "Stavka" messed up

You've gotta feel for the Soviet commanders in a way. They had just won the biggest victory in human history at Stalingrad. They were convinced the Germans were a spent force. General Filipp Golikov, who was in charge of the Voronezh Front, kept reporting that the Germans were fleeing in panic even as Manstein was literally fueling up his Panzers for the counter-attack.

- Intelligence Failure: The Soviets missed the arrival of the II SS Panzer Corps from France.

- Arrogance: Victory fever is a real thing in military history. They ignored the warning signs of their own thinning ranks.

- Logistics: The Red Army couldn't get spare parts or fuel to the front fast enough to sustain the chase.

It's a classic case of what Clausewitz called "the culminating point of victory." You push until you can't push anymore, and if you don't stop, you break. The 3rd battle of Kharkov was that breaking point.

The urban nightmare: Kharkov itself

When the II SS Panzer Corps, specifically the Leibstandarte and Das Reich divisions, reached the city, the fighting turned into a meat grinder. This is where the tactical finesse of the "Backhand Blow" turned into the ugly reality of 1940s urban warfare.

Kharkov was a city of wide squares and massive concrete buildings. The Soviets had turned it into a fortress. For several days in mid-March, the city was a hellscape of flamethrowers, hand grenades, and point-blank tank fire. The Germans eventually took it, but the cost was high. It’s estimated that the Soviets lost over 80,000 men in this period, while the Germans lost about 11,000.

Numbers like that are hard to wrap your head around. Basically, the equivalent of a small city's population was wiped out or captured in a few weeks of fighting.

💡 You might also like: Casey Ramirez: The Small Town Benefactor Who Smuggled 400 Pounds of Cocaine

What most people get wrong about the 1943 campaign

A lot of people think this victory saved Germany. It didn't. What the 3rd battle of Kharkov actually did was create the "Kursk Salient." If you look at a map of the front after March 1943, there's a huge bulge where the Soviets still held ground around the city of Kursk.

Manstein wanted to attack that bulge immediately, while the Soviets were still reeling. But Hitler hesitated. He wanted more tanks. He wanted the new Panthers. So he waited until July. By then, the Soviets had built the most dense defensive network in history.

So, in a weird way, the success at Kharkov led directly to the catastrophic failure at the Battle of Kursk. If Manstein hadn't been so successful in March, the Germans might have been forced into a more sustainable defensive posture earlier. Instead, the victory gave the Nazi leadership a false sense of hope. They thought they could still win "big" offensive battles.

Actionable insights for history buffs and strategists

If you're studying the 3rd battle of Kharkov today, whether for a history paper or just because you’re a buff, there are a few things you should actually look into to get the full picture:

- Look at the weather reports: Check out the daily temperature logs from February 1943. It explains why the German Panzers were able to move while the Soviet trucks got bogged down.

- Study the "Popov Group": This was the Soviet mobile group that got annihilated. Their failure is a masterclass in how not to manage a pursuit.

- Read the memoirs carefully: Manstein’s Lost Victories is the standard source, but keep in mind he was writing to save his own reputation. Cross-reference it with David Glantz’s work, like From the Don to the Dnepr, which uses Soviet archives to show how messy things were on the other side.

- Analyze the "Kursk" connection: Trace the front line on a map from February to July 1943. You'll see how the Kharkov victory dictated the geography of the war's most famous tank battle.

The 3rd battle of Kharkov remains one of the most studied operations in military academies like West Point or Sandhurst. It’s the ultimate example of why you should never assume your enemy is beaten until the last gun falls silent. It was a brilliant, bloody, and ultimately futile gasp of a dying military machine that only served to prolong a war that was already lost.

To truly understand this event, focus on the logistical gap between the Don and the Dnieper. That's where the battle was actually lost for the Soviets, long before the first Tiger tank fired its 88mm gun on the outskirts of the city. Analyze the transition from mobile maneuver to static urban attrition to see how tactical wins can sometimes create strategic dead ends.