Honestly, it’s kinda wild that we almost didn't get them. Most people assume the Founding Fathers just sat down, wrote the Constitution, and naturally added the 1st ten Bill of Rights as a finishing touch. That isn't what happened. Not even close. It was a messy, political brawl. James Madison, the guy we call the "Father of the Constitution," actually thought a Bill of Rights was unnecessary and maybe even dangerous at first. He called them "parchment barriers" that wouldn't actually stop a greedy government from doing whatever it wanted.

He changed his mind because he had to.

If he hadn't promised to add these protections, the Constitution probably wouldn't have been ratified by enough states to become the law of the land. Massachusetts, New York, and Virginia were skeptical. They’d just finished a war against a king, and they weren't about to hand over power to a new federal government without some serious ground rules. So, the 1st ten Bill of Rights became the ultimate "fine print" of American democracy.

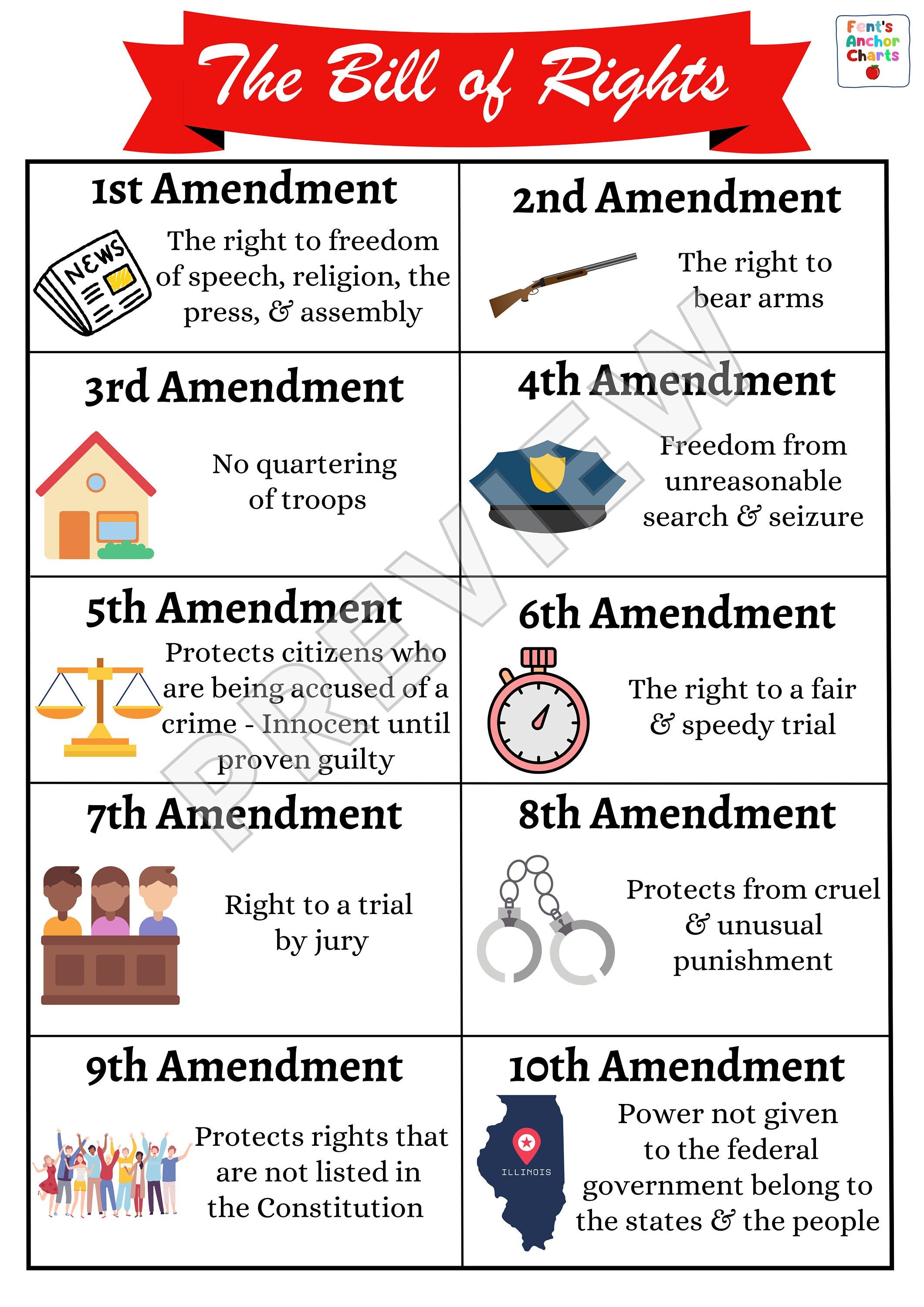

The first amendment is way broader than your Twitter feed

People scream about the First Amendment constantly, but it’s often misunderstood. It’s not just one thing; it’s a cluster of five distinct protections: speech, press, religion, assembly, and petition. It’s the "Swiss Army Knife" of the Constitution.

Back in the 1790s, the "press" meant a literal hand-cranked printing press that smelled like ink and sweat. Today, it covers everything from a TikTok video to a massive investigative report in the New York Times. But here is the kicker: it only stops the government from punishing you. It doesn't stop a private company from banning you or your boss from firing you for saying something controversial.

There’s also this weirdly persistent myth that "separation of church and state" is a phrase in the First Amendment. It’s not. That phrase actually comes from a letter Thomas Jefferson wrote to the Danbury Baptist Association in 1802. The amendment itself just says the government can't establish a religion or stop you from practicing yours. It’s a subtle but massive difference that legal scholars like Akhil Reed Amar have spent entire careers dissecting.

✨ Don't miss: Will Palestine Ever Be Free: What Most People Get Wrong

That whole thing about the Second Amendment

The Second Amendment is arguably the most debated sentence in the English language. "A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed."

For a long time, the Supreme Court didn't say much about it. Then came the 2008 District of Columbia v. Heller decision. Justice Antonin Scalia wrote the majority opinion, arguing that the amendment protects an individual's right to own a gun for self-defense, independent of militia service. But even Scalia noted that this right isn't absolute. You can't just carry a sawed-off shotgun into a courtroom and claim it's your constitutional right. The tension between "well regulated" and "shall not be infringed" is where all the modern legal fireworks happen.

The "forgotten" amendments that actually matter every day

We talk about speech and guns, but what about the Third Amendment? It says the government can't force you to house soldiers. You’ve probably never thought about it because it’s rarely been litigated. In fact, it's the only amendment the Supreme Court has never used as the primary basis for a decision. It’s a relic of the British Quartering Acts, but it represents a huge principle: your home is your castle.

Then there’s the Fourth. This is the big one for the digital age. It protects you against "unreasonable searches and seizures."

In 1791, this meant a British officer couldn't kick down your door to look for smuggled tea. In 2026, it means the police generally need a warrant to search your smartphone. Why? Because as Chief Justice John Roberts famously wrote in Riley v. California, phones are different. They contain the "privacies of life." If you’re walking down the street, the Fourth Amendment is what stands between you and a random bag search by a cop who just "has a feeling."

🔗 Read more: JD Vance River Raised Controversy: What Really Happened in Ohio

Five, Six, Seven, and Eight: The "Don't Jail Me Unfairly" block

These four amendments are basically a "how-to" guide for a fair trial.

- The Fifth Amendment is famous for the "right to remain silent." But it also covers "double jeopardy" (you can't be tried for the exact same crime twice) and "due process."

- The Sixth gives you the right to a speedy trial and a lawyer. If you’ve ever watched a police procedural, you’ve seen the Sixth Amendment in action when someone yells, "I want my attorney!"

- The Seventh is the one people forget. It guarantees a jury trial in civil cases—like if you sue someone for more than twenty bucks. It’s the reason we have a civil court system that isn't just decided by a single judge.

- The Eighth Amendment is the "cruel and unusual punishment" rule. It’s why we don't use the rack or the guillotine anymore. It also forbids "excessive bail," though what qualifies as "excessive" is a huge point of contention in modern bail reform debates.

The safety nets of the Ninth and Tenth

These two are the "just in case we forgot something" clauses.

The Ninth Amendment is fascinating. It says that just because a right isn't listed in the 1st ten Bill of Rights, it doesn't mean you don't have it. It’s an admission that the writers weren't perfect. They knew they couldn't list every single human right, so they left the door open. This is where the "right to privacy" often gets rooted, even though the word "privacy" never appears in the Constitution.

The Tenth Amendment is the "states' rights" clause. It says any power not given to the federal government belongs to the states or the people. This is why laws about driver's licenses, marriage, and education vary so much from Florida to California. It’s a built-in stabilizer to keep the central government from getting too bloated, though the 14th Amendment eventually complicated this by making sure states couldn't violate your basic rights either.

Why the Bill of Rights almost didn't happen

James Madison was a pragmatist. He saw that groups like the Anti-Federalists—led by guys like Patrick "Give me liberty or give me death" Henry—were going to tank the whole American experiment if they didn't get a written guarantee of rights.

💡 You might also like: Who's the Next Pope: Why Most Predictions Are Basically Guesswork

Madison sat down and went through hundreds of suggestions from the state ratifying conventions. He whittled them down to 12.

Wait, 12?

Yeah. The original list had 12 amendments. The states rejected two of them. One was about how many representatives would be in Congress, and the other was about when Congress could give itself a raise. Interestingly, that "pay raise" amendment actually did get ratified eventually—it became the 27th Amendment in 1992, over 200 years after it was first proposed.

The real-world impact of the 1st ten Bill of Rights today

These aren't just dusty words in a museum. They are the frontline of our legal system. When a whistleblower leaks documents, that's the First Amendment. When a judge throws out evidence because it was taken without a warrant, that's the Fourth. When a defendant refuses to testify, that's the Fifth.

It’s easy to take them for granted until you don't have them. In many parts of the world, criticizing a leader gets you prison time. In the US, the 1st ten Bill of Rights ensures that the government has to play by the rules, not the other way around.

The system isn't perfect. There are still massive debates about how these rights apply to AI, facial recognition, and data privacy. Does a "search" include a satellite looking at your backyard? Does "free speech" include an algorithm? These are the questions the next generation of lawyers will have to figure out.

Actionable steps for the modern citizen

- Read the actual text: It’s shorter than you think. You can read the whole thing in under ten minutes. Don't rely on what people say it says—read it yourself.

- Track Supreme Court dockets: Sites like SCOTUSblog offer incredible, plain-English breakdowns of how these amendments are being re-interpreted in real-time.

- Know your local laws: Since the Tenth Amendment gives so much power to states, your rights can look a bit different depending on your zip code.

- Support the First Amendment in practice: This means defending the rights of people you disagree with. If the First Amendment only protected popular speech, we wouldn't need it.

The 1st ten Bill of Rights isn't just a list of permissions. It's a list of "thou shalt nots" directed at the government. It’s the framework that keeps the American experiment running, even when things get messy. Understanding them is the first step toward keeping them.