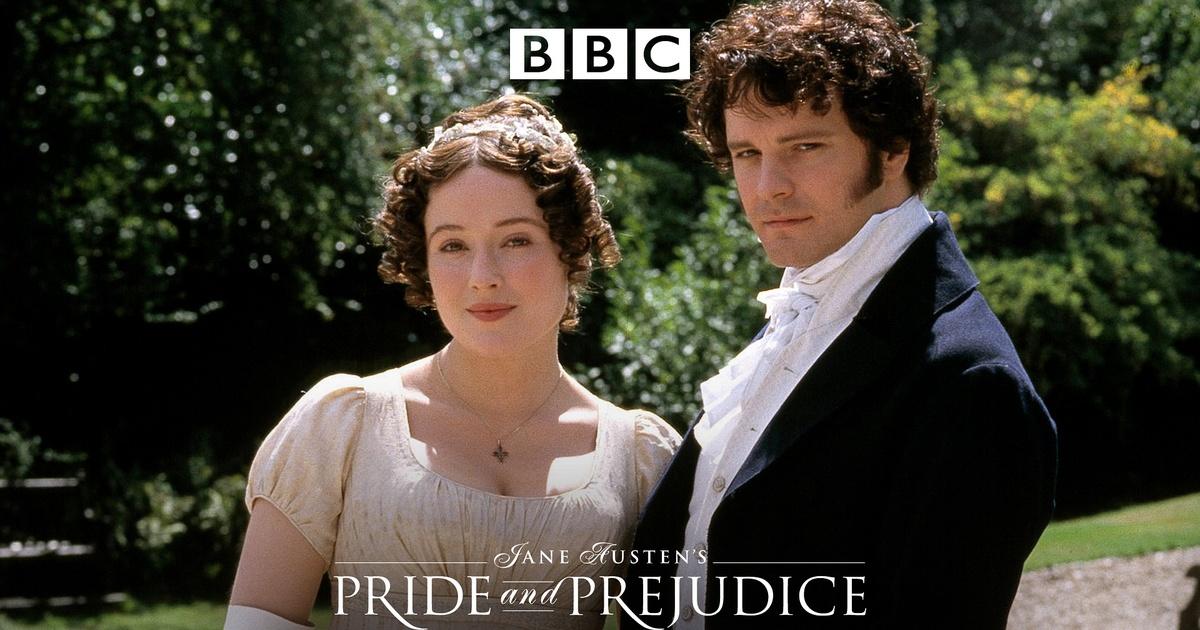

Let’s be real for a second. If you mention a Pride and Prejudice show to any period drama nerd, their mind immediately jumps to a very specific lake in Cheshire and a very wet linen shirt. We’ve had movies. We’ve had modern YouTube vlogs. We’ve even had zombies. But the 1995 BBC miniseries remains this weirdly untouchable cultural monolith that refuses to age.

It’s been decades.

Most TV shows from the mid-nineties look like they were filmed through a lens smeared with Vaseline, but this six-episode run still feels fresh. Maybe it’s the pacing. Andrew Davies, the screenwriter, basically looked at Jane Austen’s 1813 novel and realized you can’t squeeze that much social anxiety and sexual tension into a two-hour movie without losing the soul of the thing. You need the breathing room. You need the awkward silences.

Honestly, the "lake scene" wasn't even in the book. Austen never wrote about Darcy taking a plunge. But that’s the brilliance of this specific adaptation—it understood the physical tension beneath the Regency manners in a way that felt revolutionary at the time.

Why the 1995 Pride and Prejudice Show Outshines the Rest

Most people argue about Jennifer Ehle versus Keira Knightley. It’s the great debate of the Austen fandom. While Knightley’s 2005 film is visually stunning (thank you, Joe Wright), it feels like a fever dream compared to the grounded reality of the Pride and Prejudice show from '95.

The BBC version had the luxury of time.

With six hours of screen time, we actually see the slow, painful burn of Elizabeth Bennet’s realization that she’s been a bit of a jerk. It isn't just a sudden flip of a switch. We see the layers of the Bennet family’s chaos. Alison Steadman’s portrayal of Mrs. Bennet is polarizing—some find her screeching unbearable—but she’s actually playing the character exactly as Austen wrote her: a woman driven to the brink of a nervous breakdown by the very real threat of poverty. If her daughters don't marry, they lose their home. It’s high stakes masquerading as a drawing-room comedy.

Then there’s Colin Firth.

Before this show, Mr. Darcy was a literary figure, sure, but Firth turned him into a global phenomenon. He played Darcy with this stiff, almost painful social awkwardness that felt more authentic than a standard "brooding hero" trope. He’s not just mean; he’s uncomfortable. It’s a nuance that many subsequent adaptations miss.

✨ Don't miss: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

The Problem with 2005 (And Other Remakes)

Look, the 2005 movie is beautiful. The cinematography is top-tier. But it suffers from "Hollywood-itis." Everything is a bit too muddy, everyone’s hair is a bit too messy, and the ending feels like a different genre entirely.

The 1995 Pride and Prejudice show stayed faithful to the biting wit of the narration. Austen wasn't just writing romances; she was writing satire. She was making fun of everyone. The miniseries keeps that sharp edge. When Mr. Collins (played with legendary creepiness by David Bamber) enters a room, you feel the physical cringey-ness of it. It’s not just a plot point; it’s an experience.

Other versions like Lost in Austen or The Lizzie Bennet Diaries are fun experiments. They play with the format. But they always circle back to the '95 version as the ultimate reference point. Even Bridgerton, with all its neon colors and pop covers, owes its entire existence to the blueprint laid down by this miniseries.

The Production Details That Actually Mattered

People forget that this was a massive gamble for the BBC. They used Super 16mm film, which gave it a cinematic quality that most TV at the time lacked.

Director Simon Langton pushed for outdoor filming. They went to Lacock and Lyme Park. They didn't just stay in a dusty studio. This gave the show a sense of "place." You can feel the cold air in the scenes where Elizabeth is walking across the fields to Netherfield. That "fine eyes" comment from Darcy makes more sense when she actually looks like she’s been trekking through the mud.

- Costume Design: Dinah Collin didn't just make "pretty dresses." She used color palettes to distinguish the families. The Bennets are in earth tones and slightly worn fabrics. The Bingleys are in high-fashion, expensive silks that scream "new money."

- The Script: Andrew Davies is famous for "sexing up" the classics, but here he was subtle. He focused on the male gaze—showing Darcy fencing or bathing—to remind the audience that these characters had physical lives outside of tea parties.

- The Music: Carl Davis’s score uses a period-accurate chamber orchestra style but keeps it lively. It doesn't feel like a museum piece.

It’s About Class, Not Just Kisses

If you think a Pride and Prejudice show is just about girls wanting to get married, you’ve missed the point entirely. Austen was obsessed with money. Specifically, the lack of it.

The 1995 version highlights the Entail. Because Mr. Bennet has no sons, his estate goes to Mr. Collins. This is the ticking clock of the entire story. Every time Mrs. Bennet screams about her "poor nerves," she’s actually screaming about the fact that she’ll be homeless if her husband dies.

The show does a great job of showing the vast gap between Longbourn (the Bennets' house) and Pemberley (Darcy's estate). When Elizabeth finally visits Pemberley, the camera lingers on the scale of it. It’s not just a big house; it’s a kingdom. It changes the context of her refusal. She didn't just say no to a man; she said no to a level of wealth that most people couldn't even imagine.

🔗 Read more: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

That Infamous Lake Scene

We have to talk about it.

The scene where Darcy dives into the lake and then awkwardly bumps into Elizabeth while soaking wet is probably the most famous moment in British TV history. Interestingly, it wasn't in the script to be a "sexy" moment. It was meant to show Darcy shedding his aristocratic armor. He’s literally and figuratively stripped down.

It humanized him.

But it also sparked a bit of a frenzy. That single moment turned Colin Firth into a star overnight and cemented the idea that period dramas could be... well, hot. It shifted the way the BBC approached "Classic Theatre" adaptations forever. They realized that if you treat the characters like real people with real desires, the audience will show up in droves.

Common Misconceptions About the Show

People often think this version is "too long."

Honestly? It's the opposite. The length is its strength. If you watch the 1940 version with Laurence Olivier, Darcy is basically a caricature. In the '95 Pride and Prejudice show, we get to see the subtle shifts. We see Wickham’s charm slowly curdle into something slimy. We see Charlotte Lucas’s pragmatic decision to marry Mr. Collins not as a tragedy, but as a survival tactic.

Another misconception is that it’s "stuffy."

If you actually listen to the dialogue, it’s hilarious. Mr. Bennet is a world-class troll. Elizabeth’s banter with Darcy is basically 19th-century "roasting." The show captures that playfulness. It’s not a lecture; it’s a comedy of errors.

💡 You might also like: Ted Nugent State of Shock: Why This 1979 Album Divides Fans Today

Is it Still Worth Watching in 2026?

With all the new streaming content and high-budget spectacles, does a 30-year-old miniseries still hold up?

Absolutely.

There is a reason why it still trends on social media every time a new "romantasy" book drops. It’s the original "enemies-to-lovers" blueprint. The chemistry between Ehle and Firth wasn't just acting; they were actually dating during the filming, and it shows. There is a spark in their eye contact that you just can't manufacture with CGI or modern lighting.

It’s also surprisingly comforting. In a world of grimdark TV and nihilistic plots, watching a story where people learn to be better versions of themselves is actually quite radical.

How to Get the Most Out of Your Rewatch

If you’re diving back in, or watching it for the first time, don't just put it on in the background while you're on your phone.

- Watch the background characters. The show is full of little "Easter eggs" in the acting. Look at Mary Bennet’s facial expressions during the balls. Look at how the servants react to the family’s drama. It adds a whole layer of social commentary.

- Pay attention to the letters. In the Regency era, letters were the only way to communicate. The show uses voiceovers for the letters perfectly. It’s where the most honest character development happens.

- Compare the houses. The production team spent a lot of time picking locations that reflected the characters’ status. Contrast the cluttered, cozy mess of Longbourn with the cold, imposing grandeur of Lady Catherine de Bourgh’s Rosings Park. It tells a story without saying a word.

The Pride and Prejudice show from 1995 isn't just a relic of the nineties. It’s a masterclass in adaptation. It proves that you don't need to "fix" the classics—you just need to understand why they worked in the first place.

Next time someone tells you the 2005 movie is better, just remind them that only one version has a scene so iconic it has its own statue in Hyde Park. Case closed.

To truly appreciate the depth of this adaptation, consider reading the original text alongside a rewatch. Focus on the chapters covering Elizabeth's visit to Hunsford and her stay at Pemberley. These sections contain the most significant deviations and expansions in the show, particularly regarding Darcy’s internal perspective. Seeing how Andrew Davies translated Austen’s "free indirect discourse" into visual storytelling provides a much deeper understanding of why this specific version remains the definitive portrayal of the story.