Suniland, Florida. April 11, 1986. It was a Friday morning that started out feeling like any other humid, mundane shift for the FBI agents tracking a pair of brutal serial robbers. By 9:30 AM, the intersection of Southwest 82nd Avenue and 120th Street looked more like a war zone than a quiet suburb of Miami. Glass shattered. Tires screeched. People died.

The 1986 Miami FBI shootout wasn't just a gunfight. It was a slaughter that exposed every single weakness in the Bureau’s tactical approach, their weaponry, and their mindset. It’s the reason your local police officer likely carries a semi-automatic .40 caliber or 9mm pistol today instead of a wood-gripped revolver.

Honestly, if you watch the dashcam footage from modern police stops, you’re seeing the ghost of this specific morning in 1986. The FBI had the numbers. They had the training. They had the "good guy" advantage. Yet, within five minutes, two men—William Matix and Michael Platt—managed to kill two agents and wound five others while taking dozens of hits themselves. It was a wake-up call that hit the law enforcement community like a sledgehammer to the chest.

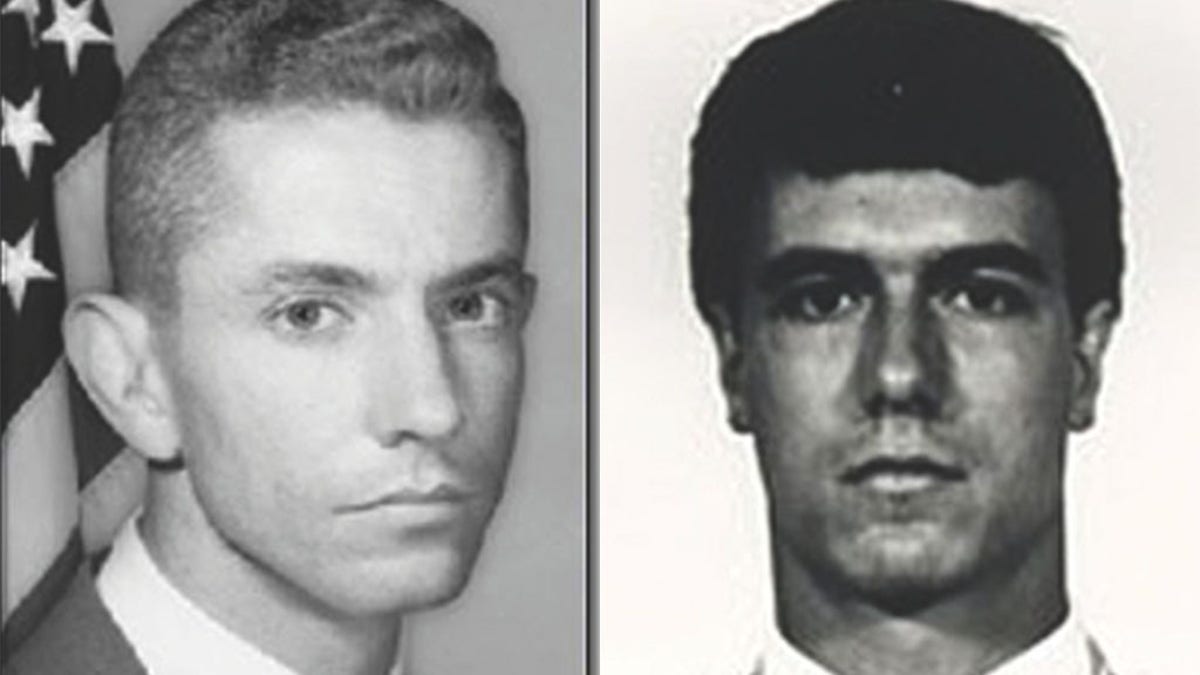

The Men Behind the Trigger

You can't understand the 1986 Miami FBI shootout without looking at who the FBI was actually chasing. This wasn't a couple of kids sticking up a 7-Eleven. William Matix and Michael Platt were former Army Rangers. They were disciplined. They were cold. They didn't just want to escape; they were willing to fight to the absolute end.

They had been on a spree. It started with killing target shooters in rock pits to steal their guns and progressed to armored car robberies. They were efficient. They used long guns—specifically a Ruger Mini-14—which gave them a massive firepower advantage over the agents' service revolvers and 9mm pistols.

When the FBI spotted their stolen black Chevrolet Monte Carlo that morning, they weren't necessarily expecting a suicide charge. But that’s exactly what they got.

Five Minutes of Absolute Hell

The stakeout team consisted of eight agents in five cars. When they tried to force the Monte Carlo off the road, the "pit maneuver" didn't go smoothly. Cars collided. Agents were pinned. Ben Grogan, a legendary shot and a veteran agent, lost his glasses in the crash. Imagine trying to engage two military-trained gunmen when you can barely see the front sight of your gun.

Jerry Dove and Grogan were in the thick of it. The noise was deafening. Agent Gordon McNeill took a hit early. Agent Edmundo Mireles was shot in the arm—shattered by a .223 round from Platt’s rifle—leaving him to fight with one hand for the rest of the engagement.

🔗 Read more: How Much Did Trump Add to the National Debt Explained (Simply)

Platt was the primary engine of destruction. Even after being shot multiple times, including a wound that collapsed his lung and stopped just short of his heart, he kept moving. He kept firing. This is the part that haunts ballistic experts. Under the "stopping power" theories of the time, Platt should have been dead or incapacitated minutes before the fight ended.

Instead, he crawled out of the car, walked up to Grogan and Dove—who were pinned behind their vehicle—and executed them at point-blank range.

The Ballistic Failure That Changed History

Why did it take so long to stop them? This is the core of the 1986 Miami FBI shootout controversy.

Agent Jerry Dove fired a 9mm Silvertip round that hit Platt in the chest. It traveled through his arm and into his chest cavity, stopping about an inch from his heart. In a lab, that’s a "fatal" wound. In the real world, Platt’s adrenaline and physiological makeup allowed him to keep killing for several more minutes.

The FBI realized their ammo sucked.

They were using 158-grain .38 Special +P rounds and early 9mm loads that lacked the penetration needed to shut down a human being instantly. When you’re in a gunfight, "eventually fatal" isn't good enough. You need "immediate incapacitation."

The Aftermath and the Birth of the .40 S&W

In the wake of the bloodbath, the FBI held a series of ballistic seminars. They weren't interested in "sorta" stopping a suspect anymore. They wanted a round that could punch through car doors, glass, and heavy clothing while still reaching the vital organs.

💡 You might also like: The Galveston Hurricane 1900 Orphanage Story Is More Tragic Than You Realized

- They briefly looked at the 10mm Auto.

- It was too powerful for most agents to handle accurately.

- They eventually collaborated with Smith & Wesson to create the .40 S&W.

This shift was seismic. Within a decade, the American police officer's holster changed entirely. The iconic Smith & Wesson Model 19 or Colt Python revolvers were relegated to museums or the back of safes. Semi-automatics with high-capacity magazines became the standard.

Edmundo Mireles: A Study in Grit

If there is a hero in the 1986 Miami FBI shootout, it’s Edmundo Mireles. With one arm dangling uselessly at his side, he managed to rack his Remington 870 shotgun against his bumper, fire, and eventually draw his revolver to finish the fight. He walked toward the suspects' car and fired the final rounds that ended the nightmare.

It was a display of sheer willpower. It also proved that training for "worst-case scenarios"—like being forced to operate your weapon one-handed—wasn't just "tacti-cool" fluff. It was life or death.

Why We Still Talk About Southwest 82nd Avenue

The site of the shootout doesn't look like much today. It’s near a Home Depot. People drive past it every day on their way to buy mulch or light bulbs, completely unaware that the asphalt beneath them was once soaked in the blood of men who fundamentally changed how every cop in America does their job.

We talk about it because it highlights the "asymmetry of violence." The agents were reactive; the gunmen were proactive. The agents had "duty" rounds; the gunmen had "war" rounds.

It also forced a massive change in how the FBI trains for vehicle stops. No more "casual" bumping. They realized that once the shooting starts, you are in a "linear danger zone." If you stay behind your open car door, you’re just hiding behind a thin sheet of metal that a .223 round will zip through like a hot needle through butter.

Lessons That Stick

If you're a student of history or law enforcement, the 1986 Miami FBI shootout offers a few brutal truths that remain relevant in 2026:

📖 Related: Why the Air France Crash Toronto Miracle Still Changes How We Fly

- Equipment matters, but mindset wins. Mireles didn't win because he had a better gun; he won because he refused to quit.

- Ballistics are unpredictable. You can do everything right and still have a "perfect" shot fail to stop a determined threat.

- Tactical errors are compounded by stress. The loss of Grogan's glasses and the chaotic positioning of the vehicles turned a 2-to-8 advantage into a desperate scramble for survival.

The Bureau eventually memorialized Grogan and Dove, naming their South Florida field office after them. But their real legacy isn't a building. It's the fact that the next generation of agents went into the field with better vests, better guns, and a much clearer understanding of the monster that lives inside a high-stakes gunfight.

Actionable Insights for Security Professionals and Historians

If you are researching the 1986 Miami FBI shootout for professional development or historical context, focus on these three areas for a deeper understanding of the shift in modern tactics:

Study the Wound Ballistics Workshop of 1987.

This was the direct result of the Miami incident. Researching the "FBI Protocol" for ammunition testing will give you the technical background on why certain calibers are chosen for duty use today. It is the gold standard for testing penetration and expansion in ballistic gelatin.

Analyze the "Fatal Funnel" in Vehicle Engagements.

Most of the casualties in Miami occurred because agents were trapped between or behind vehicles. Modern "LEO" (Law Enforcement Officer) training emphasizes moving away from the vehicle "pillbox" and finding real cover, or using the engine block specifically. Contrast the 1986 footage/diagrams with modern "Vehicle CQB" (Close Quarters Battle) tactics.

Review the Psychological Aspect of the "Will to Fight."

Read Edmundo Mireles’ own accounts of the day. His book, FBI Miami Firefight: Five Minutes that Changed the Bureau, provides a first-person perspective on the physiological effects of extreme trauma and the mental fortitude required to stay in a fight after sustaining a life-altering injury. This is a crucial study for anyone in high-risk professions.

By looking at the 1986 Miami FBI shootout not as a tragedy, but as a turning point, we respect the sacrifice of the fallen by ensuring their hard-learned lessons aren't forgotten in the haze of history.

---