It was a Wednesday afternoon. People in New England were basically going about their business, maybe complaining about the humidity or wondering if the late-September breeze felt a little "off." No one knew. They really didn't. Back then, forecasting was a shell of what we have now at the National Hurricane Center. Forecasters in Jacksonville, Florida, had actually spotted the storm days earlier, but they figured it would recurve out into the Atlantic. Standard procedure, right?

Instead, the 1938 Great New England Hurricane became a freight train.

It moved at forward speeds of nearly 50 to 70 miles per hour. That’s insane. Most hurricanes crawl. This one sprinted. By the time it slammed into Long Island and then the Connecticut coast, people didn't have hours to evacuate. They had minutes. Some had seconds. Honestly, the lack of warning is the most haunting part of the whole tragedy. You’ve got stories of people sitting down for lunch and five minutes later, their entire house is being swept into the Atlantic.

The Science of the "Long Island Express"

Why was this thing so fast? Meteorologists today call it the "Long Island Express" for a reason. A high-pressure system over the North Atlantic basically acted like a wall, while a low-pressure trough over the eastern U.S. funneled the storm straight north. It squeezed the hurricane. This created a pressure gradient that turned a standard Category 3 storm into a literal rocket.

Most people think hurricanes hit Florida and lose steam. That's usually true. But this one hit the Gulf Stream and stayed warm, and the forward motion added to the wind speed on the eastern side of the eye. If the storm is moving north at 60 mph and the internal winds are 100 mph, the right-front quadrant is hitting you with 160 mph gusts. That is F3 tornado territory, but it’s an entire wall of wind.

It made landfall on September 21. First, it hit the South Shore of Long Island, then crossed the Sound into Milford, Connecticut. But the real "right-hook" was Rhode Island.

💡 You might also like: JD Vance River Raised Controversy: What Really Happened in Ohio

Narragansett Bay and the Wall of Water

Rhode Island got absolutely leveled. Because of the shape of Narragansett Bay, the storm surge didn't just rise; it funneled. It’s like pouring a bucket of water into a funnel—it has nowhere to go but up. In Providence, the water rose almost 14 feet above the normal high tide mark.

Imagine walking down Westminster Street in downtown Providence. Suddenly, you see a 20-foot wall of water coming at you. That's not a metaphor. It actually happened. People were climbing onto the roofs of parked cars, then onto the second stories of department stores. There’s a famous, somewhat grim story about a man who bought a new barometer that morning in New York. He saw the needle buried in the "Stormy" section and thought the device was broken, so he went back to the store to complain. By the time he got home, his house was gone.

The Damage Nobody Talks About

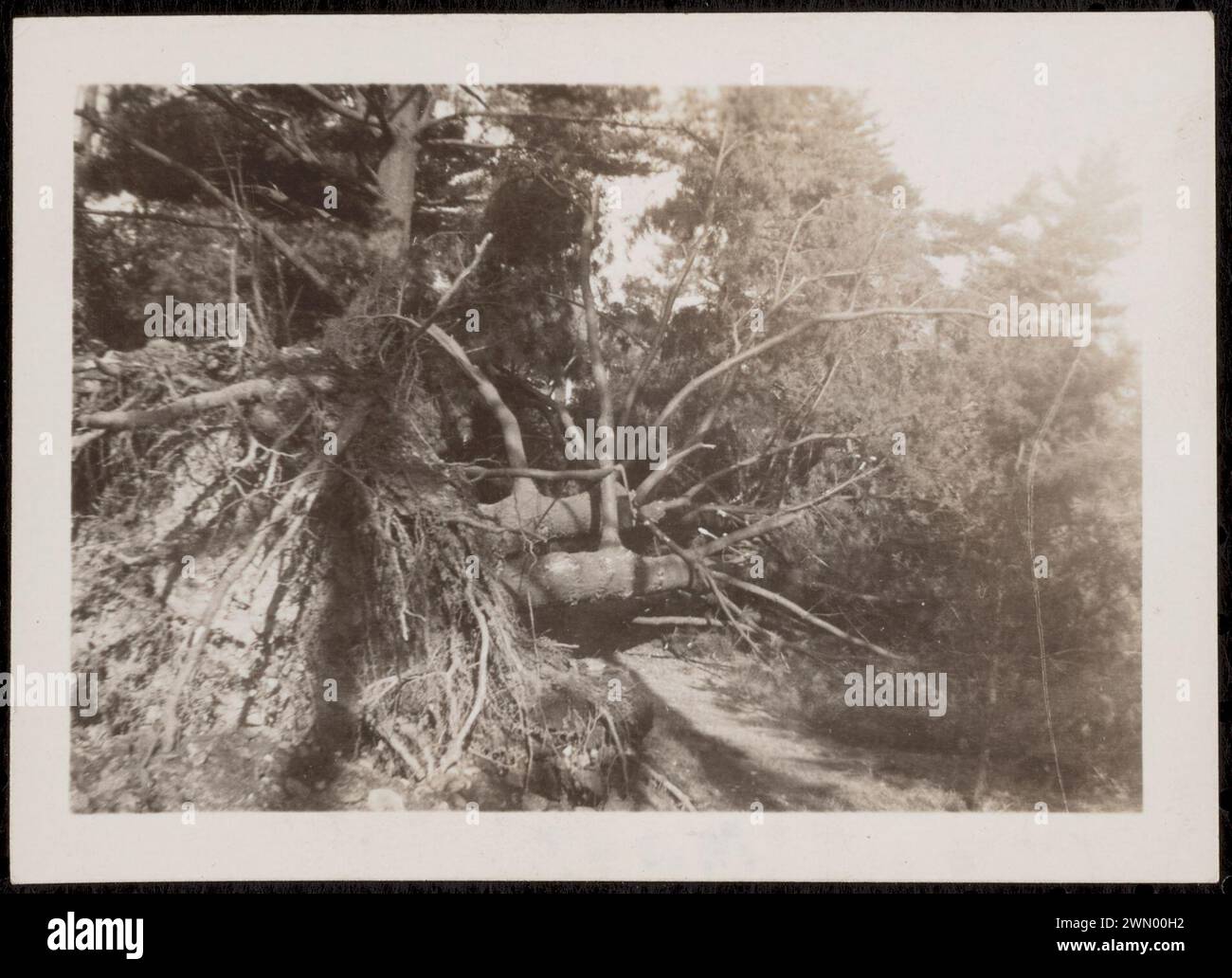

We talk about the deaths—somewhere between 600 and 800 people died, depending on which record you trust—but the ecological damage was a generational scar. New England used to be defined by its massive, old-growth white pines.

The 1938 Great New England Hurricane knocked down an estimated 2 billion trees.

Two billion.

📖 Related: Who's the Next Pope: Why Most Predictions Are Basically Guesswork

In some parts of New Hampshire and Vermont, the forests were flattened like toothpicks. It changed the landscape of the Northeast for a century. The lumber industry had to scramble to salvage the wood before it rotted, leading to the creation of the Northeastern Timber Salvage Administration. They even stored logs in ponds to keep the bugs out. If you go hiking in certain parts of the White Mountains today, you can still see "pillow and cradle" topography—mounds of earth left behind by the root balls of trees that fell during the '38 storm.

Why the Forecast Failed

We can’t blame the 1938 meteorologists too harshly, but it's important to understand the hubris involved. Charles Pierce, a junior forecaster at the time, actually predicted the storm would hit New England. He was overruled by his seniors. The "experts" thought it was physically impossible for a hurricane to maintain that much strength so far north. They were relying on old data and a bit of regional bias.

Also, there were no satellite images. No Reconnaissance aircraft flying into the eye. They relied on ship reports. If a ship didn't sail through the eye and survive to radio it in, the Weather Bureau was flying blind. On that day, the ships were quiet.

Misconceptions and the "Tsunami" Myth

A lot of survivors reported seeing a "fog bank" or a "mud flats" appearing where the ocean should be. This was actually the storm surge approaching. Because it was so dark and filled with debris, it didn't look like a blue wave from a movie. It looked like a solid wall of earth moving at 50 mph.

People often call it a tsunami. It wasn't. It was a pure meteorological surge, but the effect was the same. In Westerly, Rhode Island, the entire community of Misquamicut was basically erased. Out of 500 houses, maybe 50 were left standing.

👉 See also: Recent Obituaries in Charlottesville VA: What Most People Get Wrong

- The Wind: Blue Hill Observatory in Massachusetts recorded a peak gust of 186 mph. That remains one of the highest wind speeds ever recorded at a low altitude.

- The Flooding: It wasn't just the coast. The storm dumped heavy rain on ground that was already saturated from a week of storms. The Connecticut River crested at levels that haven't been seen since.

- The Power: It was the first time in history that power outages were so widespread that utility companies had to bring in crews from other states. This basically birthed the modern "mutual aid" system utilities use today.

What the 1938 Great New England Hurricane Taught Us

This storm changed everything about how the U.S. handles weather. It led to the creation of a more robust warning system and eventually the development of better radar. It proved that New England isn't "immune" to tropical systems.

The reality is that we are overdue. The 1938 storm was a 1-in-100-year event. We’re coming up on that 100-year mark soon. With sea levels higher than they were in the 1930s, a repeat of the 1938 Great New England Hurricane today would cause billions more in damage and potentially trap thousands of people who have moved into flood zones that didn't exist back then.

If you live on the coast, you've gotta realize that the geography of the Northeast—the way Long Island acts as a ramp and the bays act as funnels—makes it a unique trap for fast-moving storms.

Actionable Steps for Modern Preparedness

Don't wait for the "official" word if the sky looks wrong and the barometer is dropping. Modern forecasting is great, but "The Express" proved that speed is a killer.

- Audit your flood zone: Don't trust 1938 data or even 1990 data. Use the latest FEMA maps, but acknowledge they are often conservative. If you are near a tidal river, you are at risk.

- Tree maintenance: Most of the damage in '38 came from falling timber. If you have old oaks or pines hanging over your roof, get them assessed.

- The "Go-Bag" isn't just for California: In 1938, people lost their IDs, their deeds, and their money in minutes. Keep digital copies of everything on a cloud server and physical copies in a waterproof bag.

- Understand the "Right-Side" Rule: If a hurricane is projected to pass to the west of you, you are on the "dirty side" or the "dangerous semicircle." This is where the wind and surge are maximized. If the eye is hitting New Jersey, New York and Connecticut are actually in more danger from the surge.

The 1938 storm wasn't a fluke; it was a reminder. The Atlantic is a powerful neighbor, and sometimes, it decides to move in.