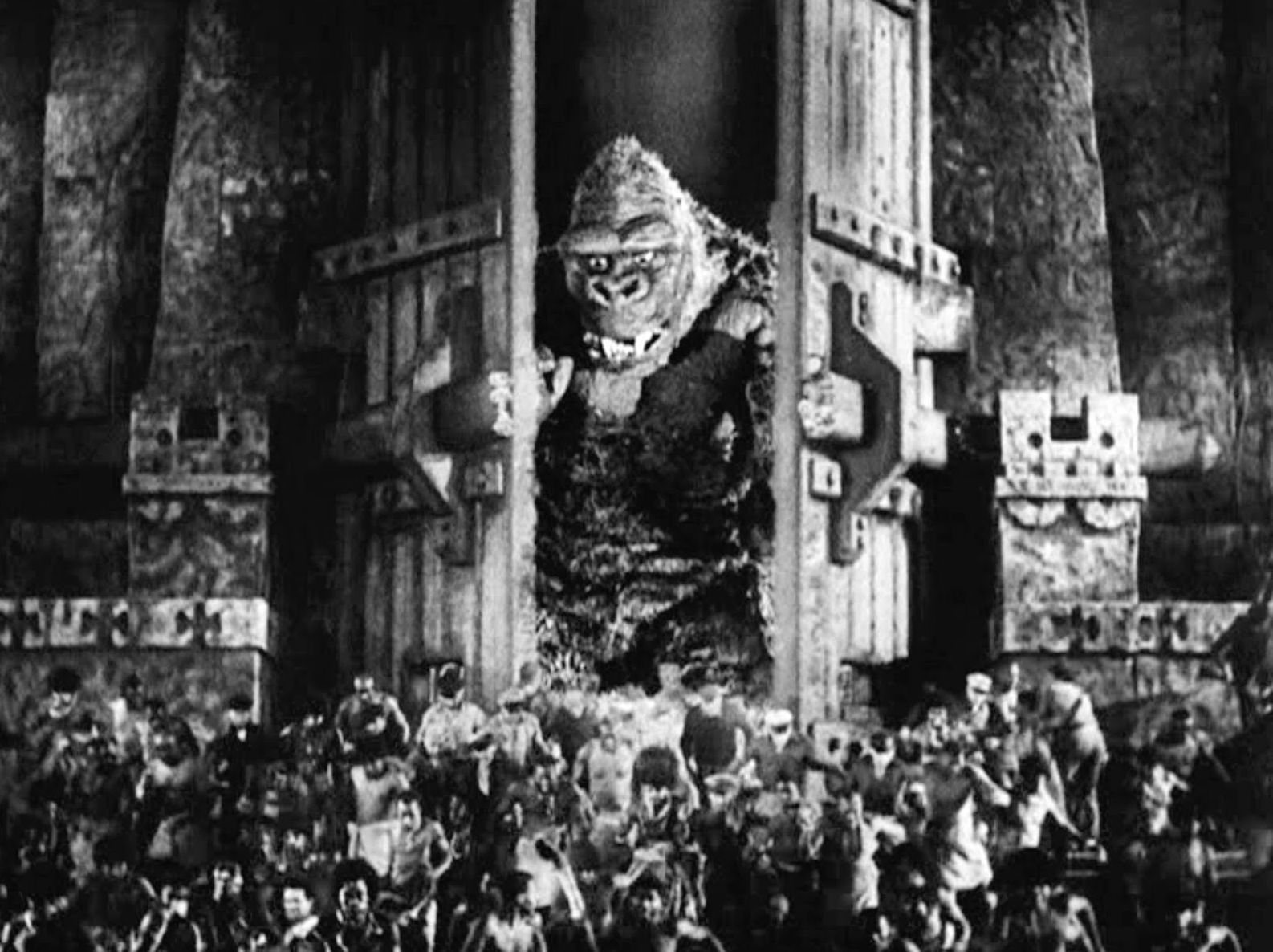

It’s hard to imagine now, but back in the early 1930s, the idea of a giant ape climbing the Empire State Building wasn't a "classic." It was a massive gamble. RKO Radio Pictures was struggling. The Great Depression was suffocating the box office. Yet, Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack decided to throw everything they had at a stop-motion nightmare that would change cinema forever. But while the creature—animated by the legendary Willis O'Brien—is the star, the 1933 King Kong cast is what actually sold the terror. Without the humans, Kong is just a rubber puppet. You need faces that scream convincingly. You need a hero who looks good in a dirty shirt. And honestly? You need a damsel who can do more than just faint.

Fay Wray: More Than a Scream Queen

When people talk about the 1933 King Kong cast, Fay Wray is the first name that pops up. Usually, it's followed by "The Scream Queen." But that’s kinda reductive. Wray was already a seasoned pro by the time she played Ann Darrow. She had worked with directors like Erich von Stroheim and Michael Curtiz. Cooper famously told her he was going to cast her with the "tallest, darkest leading man in Hollywood." She thought he meant Clark Gable. Instead, he showed her a sketch of a gorilla.

She played Ann Darrow with a specific kind of desperate vulnerability that worked because it felt real. Remember, the character starts as a starving woman stealing an apple. Wray brought a grit to those opening scenes that people forget because they’re too busy focused on the jungle stuff. She spent hours—literal days—on a high platform recorded her screams. She later joked that she "screamed her head off" for the Foley artists. The blonde wig she wore was a practical choice, too; it provided better contrast against Kong's dark fur in the black-and-white cinematography.

Robert Armstrong and the Ego of Carl Denham

If Fay Wray is the heart, Robert Armstrong is the engine. As Carl Denham, Armstrong basically played a version of the directors themselves—obsessed, reckless, and borderline unethical. It’s a fascinating performance because Denham isn't a villain, but he’s definitely the guy who causes all the problems. Armstrong had this fast-talking, "let's go get 'em" energy that defined the era's adventure films.

He stayed busy, too. Armstrong appeared in over 100 films, but he never quite escaped the shadow of Skull Island. He even returned for the rushed sequel, The Son of Kong, which came out the very same year. Talk about a quick turnaround. His delivery of the final line—"It was Beauty killed the Beast"—is arguably the most famous piece of dialogue in monster movie history. He nailed the cadence. It wasn't overly dramatic; it was almost observational, which made it stick.

📖 Related: Alfonso Cuarón: Why the Harry Potter 3 Director Changed the Wizarding World Forever

Bruce Cabot: The Accidental Leading Man

Then there’s Jack Driscoll. Bruce Cabot played the rugged first mate who eventually rescues Ann. Fun fact: Cabot wasn't even an actor when he met Cooper. He was working as a bouncer at a club. Cooper liked his look—squinty eyes, strong jaw, looked like he could actually handle a boat—and put him in the 1933 King Kong cast despite his lack of experience.

You can kind of tell, honestly. He’s a bit stiff compared to Wray and Armstrong. But that stiffness works for a sailor who’s supposed to be "tough" and "not much of a lady's man." His chemistry with Wray feels earned because it’s so awkward at first. Cabot went on to have a huge career, eventually becoming a staple in John Wayne’s inner circle, appearing in films like The Green Berets and Big Jake. He lived a wild life, but he’ll always be the guy who went down into the spider pit and lived.

The Supporting Players and Hidden Faces

The rest of the cast is a mix of reliable character actors and some very busy extras. Frank Reicher played Captain Englehorn. He had this perfect "I’ve seen everything on the seven seas" vibe. He was a German-born actor who brought a much-needed gravity to the more fantastical elements of the script.

- Noble Johnson: He played the Native Chief on Skull Island. Johnson was a pioneer in Black cinema, having founded the Lincoln Motion Picture Company. He was often cast in "ethnic" roles due to his features, but he was a highly respected professional in an era that wasn't kind to minority actors.

- James Flavin: He played Second Mate Briggs. If his face looks familiar, it’s because he played a cop or a sailor in about a thousand movies. He’s the ultimate "That Guy" of the 1930s.

- Victor Wong: Playing Charlie the Cook. This was a rare (for the time) role for a Chinese actor that wasn't purely a caricature, though it still has its 1933-era baggage.

One of the coolest bits of trivia is that the directors themselves, Cooper and Schoedsack, are actually in the movie. During the final climax, they realized they didn't want to pay extras to fly the planes that shoot Kong. So, they climbed into the cockpit of the Curtiss O-39 Helldivers themselves. Cooper reportedly said, "We should kill the son of a bitch ourselves." So, when you see the pilots shooting at the ape, you're looking at the guys who birthed the legend.

👉 See also: Why the Cast of Hold Your Breath 2024 Makes This Dust Bowl Horror Actually Work

Why the Performances Still Hold Up

Usually, 1930s acting feels like "capital-A Acting." It’s loud. It’s theatrical. But the 1933 King Kong cast managed to ground a story that should have been ridiculous. They reacted to things that weren't there. Keep in mind, when Wray is looking up in terror, she’s looking at a ball of cotton on a stick or a bare wall. The stop-motion Kong was only about 18 inches tall. To sell that as a fifty-foot god requires a level of imagination that modern actors, even with green screens, sometimes struggle with.

The film relies heavily on "reaction shots." The editor, Ted Cheesman, knew that for the audience to believe in Kong, they had to see the belief in the actors' eyes. When the Venture crew stands at the base of the Great Wall, their collective awe sets the scale. It's a masterclass in ensemble reacting.

The Physicality of the Production

It wasn't a comfortable shoot. The jungle sets were leftover from The Most Dangerous Game (1932), and they were cramped and dusty. The cast had to navigate fake foliage that was often flammable or just plain uncomfortable. Wray had to be held in a giant mechanical hand—one of the few full-scale props built for the film. It was powered by several men pumping levers to move the fingers. She was often hoisted ten or fifteen feet in the air, terrified that the grip would slip. That look of fear? Not entirely acting.

What Happened to Them?

Life after Kong was different for everyone. Fay Wray became an icon, but she eventually grew tired of the "Scream Queen" label, though she embraced it later in life. She almost had a cameo in Peter Jackson’s 2005 remake, but she passed away just before filming at the age of 96. The Empire State Building dimmed its lights in her honor.

✨ Don't miss: Is Steven Weber Leaving Chicago Med? What Really Happened With Dean Archer

Robert Armstrong kept working until the 60s, mostly in television. Bruce Cabot became a Hollywood legend in his own right, known as much for his off-screen carousing as his acting. They all remained part of a very exclusive club: the people who survived the first great monster movie.

Expert Insight: How to Appreciate the Cast Today

To truly understand the 1933 King Kong cast, you have to watch the "lost" scenes—or at least read about them. The infamous "Spider Pit" sequence was cut because it was too horrifying for 1933 audiences. The actors had to perform scenes of utter, visceral terror that were deemed "too much" by the censors. When you watch the film now, look at the sweat. Look at the way Armstrong grips his camera. It’s a gritty, tactile movie.

Actionable Steps for Film Buffs:

- Watch "The Most Dangerous Game" first: It features Robert Armstrong and Fay Wray, filmed on the same sets at the same time. It’s like a weird alternate universe version of Kong.

- Focus on the eyes: In the 1933 version, watch how often the actors look past the camera. It’s a technique used to make the "monster" feel larger than the frame.

- Check out the 1933 "The Son of Kong": See Armstrong reprise his role as a broken, guilt-ridden Denham. It adds layers to his performance in the original.

- Listen to the score: Max Steiner’s music is basically a member of the cast. It tells the actors when to be scared and the audience when to feel pity.

The legacy of the 1933 King Kong cast isn't just that they were in a famous movie. It’s that they pioneered a style of "creature feature" acting that we still see in blockbusters today. They had to make the impossible look possible. And nearly a century later, when that giant ape falls from the tower, we still feel the weight of it—not because of the stop-motion, but because of the people watching him fall.