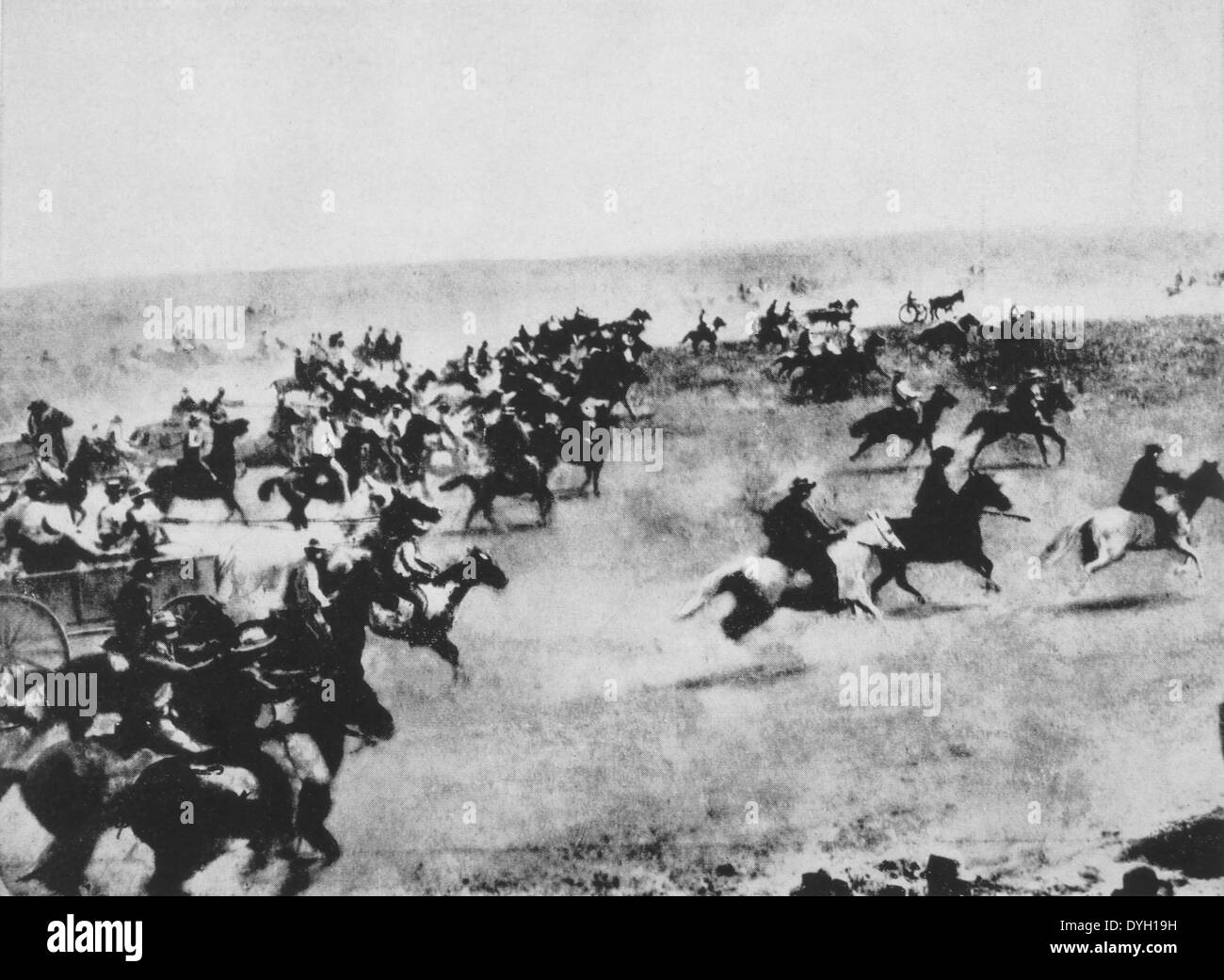

Imagine standing on a literal line in the dirt with 100,000 other people. Some are on thoroughbred horses. Others are crammed into wagons, riding bicycles, or just standing there with sturdy boots and a lot of hope. You're staring out at six million acres of tallgrass prairie. It’s hot. The dust is already choking you before the race even begins. This wasn't a movie set. It was high noon on September 16, 1893. The land run Oklahoma 1893—specifically the Cherokee Outlet opening—wasn't just some dusty historical footnote. It was the largest, loudest, and most chaotic land run in the history of the United States.

Honestly, the sheer scale of it is hard to wrap your head around. We’re talking about a strip of land roughly 58 miles wide, stretching from the 96th to the 100th meridian. This wasn't the first land run in the territory, but it was the "Big One." By 1893, the frontier was closing. People were desperate. Economic depression—the Panic of 1893—had hit the country hard. Families were hungry for a second chance, or maybe just a first chance at owning anything at all.

The Messy Reality of the Cherokee Outlet

History books kinda sanitize this stuff. They make it sound like a grand sporting event. It wasn't. The land run Oklahoma 1893 was born out of a mix of political pressure and broken treaties. The Cherokee Nation had used this land for generations as a buffer and a resource, but the U.S. government pressured them into selling it for about $8.5 million. That sounds like a lot, but for six million acres of prime grazing and farming land? It was a steal.

You had people living in "Boomer" camps for months. They were basically camping out, staring at the land they wanted, waiting for the legal "Go." When the day finally came, it was pure bedlam. Soldiers from the 9th and 10th Cavalries—the Buffalo Soldiers—were tasked with keeping order. They had to patrol the borders to keep "Sooners" from sneaking in early.

Did it work? Not really.

Sooners were everywhere. These were the guys who hid in brush piles or ravines days before the race started. By the time the honest settlers arrived on their exhausted horses, the Sooners were already sitting on the best creek-side plots, acting like they’d just arrived. It created a legal nightmare that lasted for decades. You’d have two or three people claiming the same 160-acre plot. They’d end up in "land offices" in Perry, Enid, or Alva, arguing until they were blue in the face. Sometimes they’d just fight it out with fists or guns.

📖 Related: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

Why the Land Run Oklahoma 1893 Was Different

If you look at the 1889 run—the one that founded Oklahoma City—it was smaller. The 1893 event was the varsity version. It covered more ground and had more participants. Also, the government tried to be "organized" this time. They set up registration booths.

That was a disaster.

The heat was brutal. September in the southern plains isn't exactly a breeze. Thousands of people had to stand in mile-long lines just to get a certificate saying they were allowed to run. There wasn't enough water. People fainted. Horses died of dehydration before the starting gun even fired. Some people got so fed up they just left before the race started, trading their dreams of a homestead for a drink of water and a ticket back East.

The Logistics of a 19th-Century Dash

- The Horsemen: These guys had the best shot. If you had a fast horse, you headed for the townlots or the river bottoms.

- The Trains: The Santa Fe and Rock Island railroads ran "land run trains." They were supposed to go no faster than a horse, but people were hanging off the roofs and jumping off moving cars to stake their claims.

- The Walkers: Imagine trying to race for land on foot against a guy on a horse. These folks usually ended up with the "leftovers"—rocky soil or land far from water.

The geography of the Outlet shaped how the run played out. The eastern side, near the Cross Timbers, was scrubby and wooded. The western side opened up into the vast, flat plains. Most people wanted the middle—the Salt Fork of the Arkansas River valley. It was fertile. It was flat. It was perfect for wheat.

Life After the Dust Settled

Winning the race was only about 5% of the battle. Once you stuck your "shingle" or flag in the ground, you had to keep it. You had to go to a land office, file your claim, pay a small fee, and then live on that land for five years to "prove up."

👉 See also: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

Most people lived in "soddies." Since there weren't many trees on the prairie, they literally cut bricks out of the earth and stacked them. Your roof was grass. When it rained, it leaked for three days. When the sun came out, bugs fell from the ceiling into your soup. It was a gritty, grueling existence.

The land run Oklahoma 1893 created towns overnight. Enid, Perry, and Woodward didn't exist at breakfast; by dinner, they had populations in the thousands. People were selling "city lots" out of the back of wagons. Tents served as banks, post offices, and saloons. It was instant civilization, and it was incredibly messy.

What We Often Forget

We talk a lot about the settlers, but we should talk about the displacement. This land was Cherokee land. Before that, it was used by many tribes for hunting. The "opening" of the Outlet was another nail in the coffin of the communal land ownership system of the Native American tribes. The Dawes Act had already started breaking up tribal lands into individual allotments, and the land runs were the final push to fill the "surplus" with white settlers.

It’s also worth noting the diversity of the run. There were Black homesteaders looking for freedom from the Jim Crow South. There were European immigrants who barely spoke English but understood the value of 160 acres. This wasn't a monolithic group of people. It was a desperate, hopeful melting pot.

Practical Insights for History Buffs and Researchers

If you're researching the land run Oklahoma 1893, don't just look at general histories. The real gold is in the claim files. The National Archives holds the "Land Entry Case Files." These documents often contain the personal testimony of the settlers. You can see their struggle in their own handwriting—how they built their first house, what crops they planted, and who they had to sue to keep their land.

✨ Don't miss: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

If you want to experience the scale of this thing today, go to the Cherokee Strip Regional Heritage Center in Enid. They have original buildings from the era. You can stand in a land office and realize just how small and cramped it felt while thousands of angry, sweaty people waited outside.

Also, check out the Great Salt Plains. It’s a bizarre, beautiful landscape that the settlers had to navigate. It’s one of the few places where the geography looks exactly like it did in 1893.

Moving Forward With This History

To really understand the land run Oklahoma 1893, you have to look past the romanticized "Wild West" imagery. It was a massive government-sanctioned land grab that rewarded the fast and the lucky, often at the expense of the honest and the indigenous.

Actionable Steps for Further Exploration:

- Search the BLM GLO Records: The Bureau of Land Management has a searchable database of land patents. If you think your ancestors were in the 1893 run, you can find their actual land title there.

- Visit the Pioneer Woman Museum: Located in Ponca City, it offers a deep look at the women who survived the run—who were often left to run the homestead alone while husbands went back East to earn cash.

- Read "The 101 Ranch" History: Much of the land run history is tied to the Miller brothers and their famous ranch, which was a hub of activity in the Outlet.

- Analyze the "Sooner" Legal Cases: Look into the Supreme Court case Smith v. Townsend. It set the precedent for what constituted a "legal" settler versus a Sooner. It's a fascinating look at how the law tried (and often failed) to handle the chaos of the run.

The legacy of 1893 is still visible in the grid-like roads of Northern Oklahoma today. Every mile, there's a road. Every 160 acres, there was a dream. Some of those dreams turned into dust during the 1930s, but the grit of the people who stood on that line in 1893 is what built the state. It wasn't pretty, and it certainly wasn't fair, but it was undeniably American.