You probably don't think much about the steel in your car or the beams in your local skyscraper. But back in the late fifties, that metal was the lifeblood of the entire planet. When 500,000 workers walked off the job on July 15, the steel strike of 1959 didn't just stop production; it basically threatened to snap the American economy in half. It wasn't just about pennies an hour. It was a brutal, months-long staring contest between industrial titans and a union that refused to blink.

Imagine half a million people just... stopping.

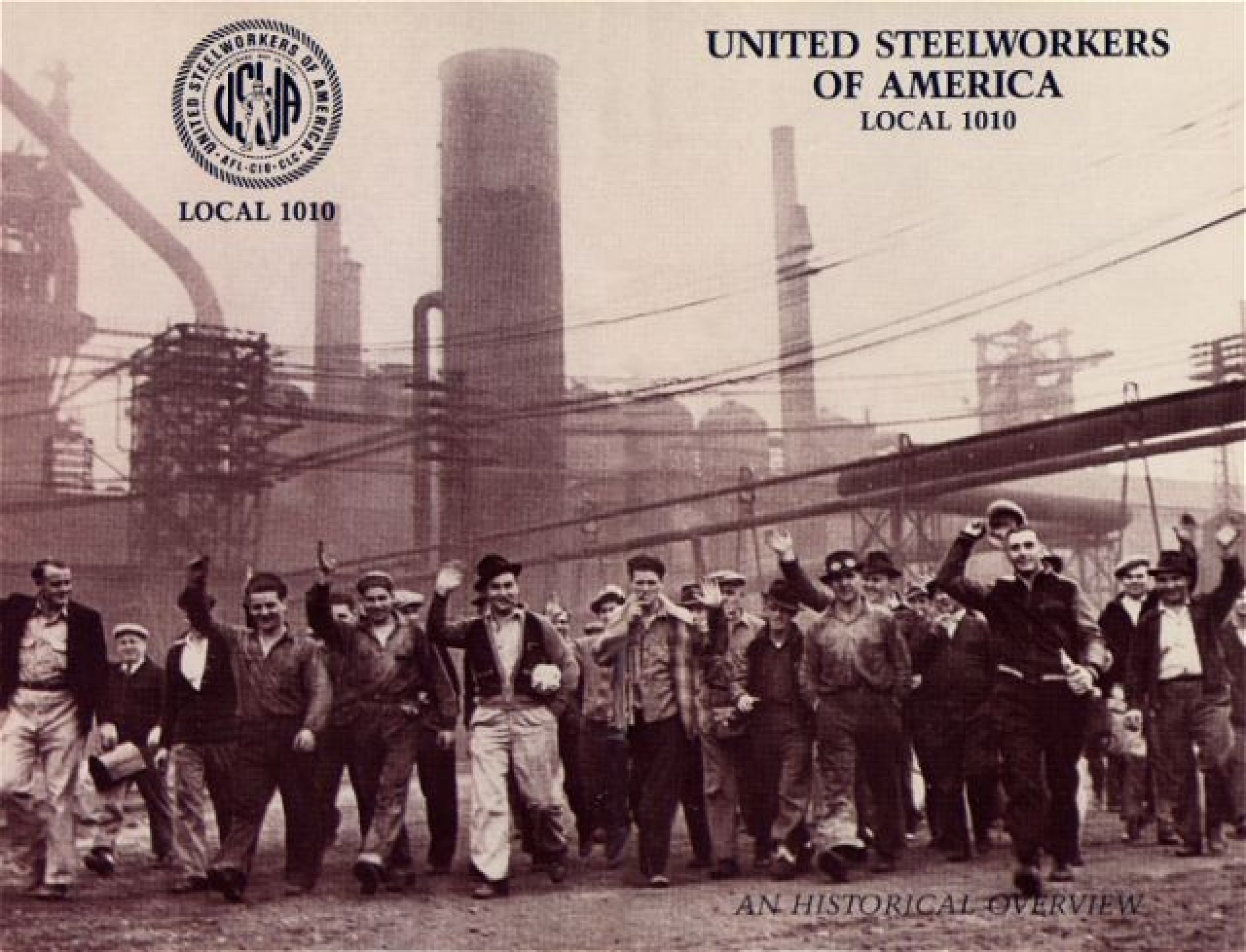

The United Steelworkers of America (USWA) weren't just asking for more cash. They were fighting for the right to keep their work rules. Management wanted to modernize. They wanted to change how the shops were run to compete with rising foreign steel. The workers saw that as a direct attack on their dignity and their job security.

Why the Steel Strike of 1959 Was Actually About Power, Not Just Pay

Most folks assume strikes are always about the paycheck. Honestly, that’s a massive oversimplification. In 1959, the steel companies—led by big shots at U.S. Steel like Conrad Cooper—weren't actually hurting for money. They were worried about "featherbedding." That's a term you don't hear much now, but it basically meant keeping workers on the payroll for jobs that new technology had made obsolete.

Management wanted to gut Section 2-B of the contract.

This specific clause protected local working conditions. It was the "don't mess with our rhythm" rule. If a crew had always had five guys, management couldn't suddenly make it three just because they bought a faster machine. David McDonald, the president of the USWA, knew that if he gave up 2-B, the union was basically toast. He had to keep the rank-and-file together even as the months dragged on and the bank accounts started looking pretty empty.

💡 You might also like: Business Model Canvas Explained: Why Your Strategic Plan is Probably Too Long

The companies figured the workers would cave once the winter chill hit and the fridge got bare. They figured wrong.

The Eisenhower Headache and the Taft-Hartley Gamble

President Dwight D. Eisenhower was in a rough spot. He hated intervening in private business disputes. He really did. But by October, the "Cold War" wasn't just a phrase; it was a constant pressure. The U.S. needed steel for missiles, for infrastructure, and to prove that capitalism wasn't about to crumble. The steel strike of 1959 was making the country look weak on the global stage.

The economy was bleeding.

Eisenhower eventually had to pull the trigger on the Taft-Hartley Act. This was a "back-to-work" order that forced a 80-day cooling-off period. It's a controversial move even today. The workers went back to the mills in November, but they weren't happy. They were "working under an injunction," which is basically like being forced to date someone you’re currently suing.

It was awkward. It was tense. And everyone knew that if a deal wasn't reached by the time those 80 days were up, the furnaces would go cold again, right in the middle of winter.

📖 Related: Why Toys R Us is Actually Making a Massive Comeback Right Now

Vice President Nixon Steps Into the Ring

It’s easy to forget that Richard Nixon played a massive role here. He was eyeing the 1960 presidency. He knew that if the strike flared back up in January, his chances against a young John F. Kennedy were basically zero. Nixon, along with Labor Secretary James Mitchell, started leaning hard on the steel executives.

They basically told the companies: "Look, if you don't settle this, Congress is going to pass laws that you'll hate way more than this union contract."

The pressure worked. On January 4, 1960, a deal was finally struck. The workers got their wage increases—about 7 cents an hour—and more importantly, they kept those precious work rules. Management didn't get the total control they craved.

The Long-Term Fallout Most People Miss

The steel strike of 1959 was a victory for the union, but it was a bit of a Pyrrhic one. While the workers won the battle over work rules, the 116-day shutdown gave foreign competitors a massive opening. Countries like Japan and West Germany started flooding the U.S. market with cheaper steel while our mills were dormant.

American buyers realized they didn't have to rely solely on Pittsburgh or Gary.

👉 See also: Price of Tesla Stock Today: Why Everyone is Watching January 28

Once that door opened, it never really shut again. The strike arguably accelerated the decline of the American "Steel Belt" into the "Rust Belt." It showed that even the most powerful domestic industry could be disrupted if the friction between labor and capital got too hot.

You also have to consider the psychological toll. 500,000 families went without a steady paycheck for nearly a third of a year. That changes a community. It changes how people trust their employers.

Practical Lessons from the 1959 Conflict

If you’re looking at this from a modern business or labor perspective, there are a few "boots on the ground" takeaways that still apply today.

- Work rules matter more than wages: In any negotiation, the "how" we work is often more contentious than the "how much" we get paid. Protecting autonomy is a core human drive.

- External competitors love internal strife: While the USWA and U.S. Steel were fighting, the rest of the world was building better mills.

- Government intervention is a blunt instrument: Taft-Hartley stopped the strike, but it didn't fix the resentment. Forced labor (even paid) rarely leads to high productivity.

- Inventory management is a weapon: Companies tried to stockpile steel before the strike, but 116 days is a long time to hold out.

To really understand the steel strike of 1959, you should look into the specific history of your own region's industrial base. Check out the local archives or historical societies in places like Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, or Youngstown, Ohio. They often have oral histories from the actual families who lived through those 116 days. It’s one thing to read about "labor statistics," but it’s another to hear about the Christmas when there were no toys because the strike was still dragging on.

Digging into those personal accounts gives you a much clearer picture of why these workers were willing to risk everything for a clause in a contract. It wasn't just stubbornness; it was survival.