July 5, 1954. It was hot. It was humid. Memphis felt like a pressure cooker.

Inside Sun Studio, a nineteen-year-old truck driver named Elvis Presley was failing. He’d been trying to sing ballads for hours. Sam Phillips, the owner of the studio, wanted something special, but all he was getting was a mediocre imitation of Dean Martin. It was boring. Honestly, it was a disaster.

Then it happened. During a break, Elvis grabbed his guitar and started flailing. He began pounding out a frantic, sped-up version of an old blues song. He was joking around. He was being a kid. Bill Black picked up his double bass and started slapping the strings to keep up. Scotty Moore joined in on guitar.

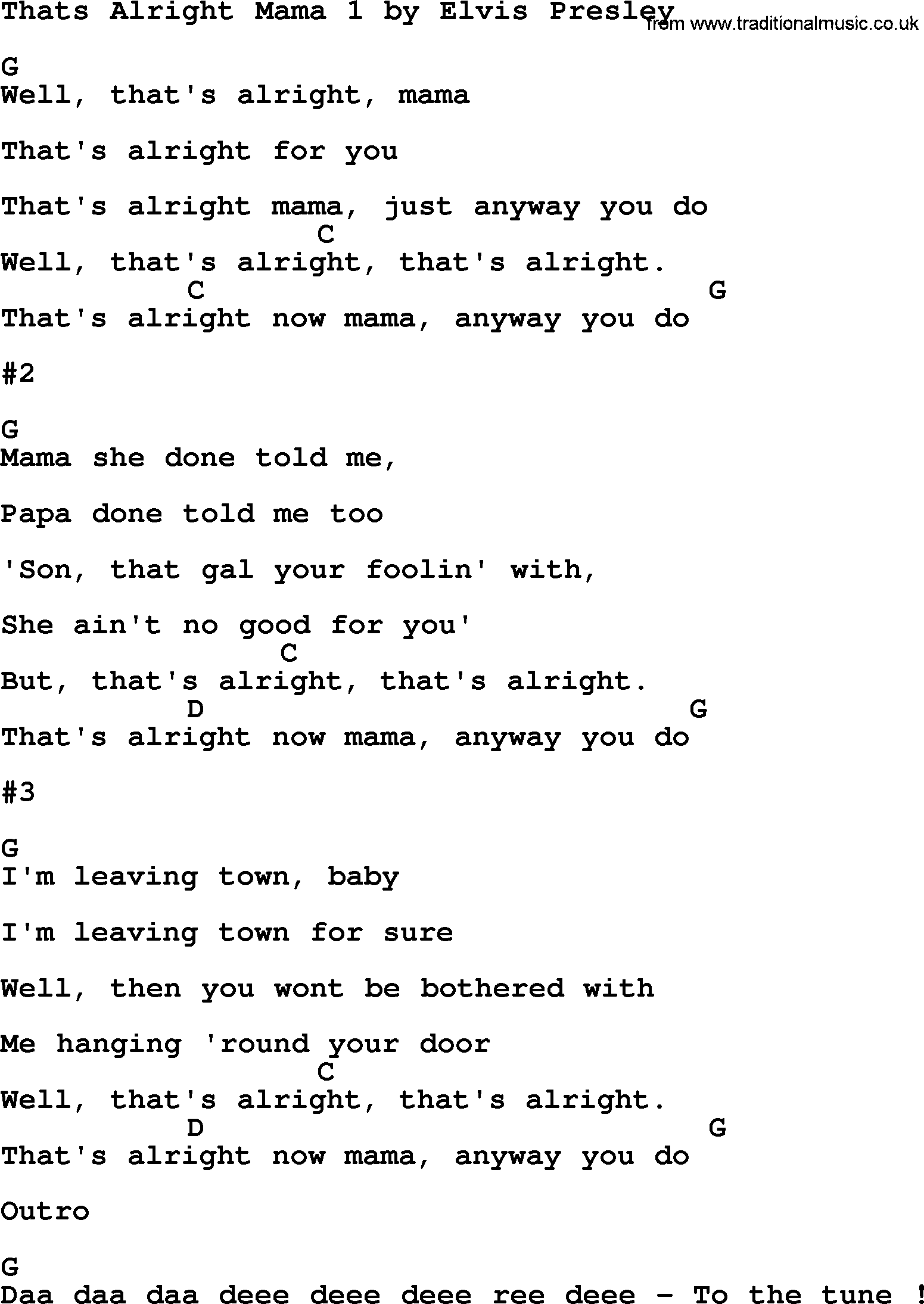

Sam Phillips poked his head out of the control room. "What are you doing?" he asked. They didn’t know. "Well, find a starting place and do it again," Sam told them. That "it" was That’s All Right Mama, and music was never the same after that night.

The Song Elvis "Stole" (But Not Really)

We have to talk about Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup. He wrote and recorded the original version of "That’s All Right" in 1946. If you listen to Crudup’s version, it’s a down-home, rhythmic blues track. It’s soulful. It’s gritty. But it isn't rock and roll.

Elvis didn't just cover it; he mutated it. He took the "race music" of the Delta and infused it with the "hillbilly" twang of the Grand Ole Opry. People often throw around the word "appropriation," and while the racial dynamics of 1950s Memphis were undeniably exploitative, Elvis’s relationship with the blues was born of genuine, obsessive fandom. He lived in the Shake Rag neighborhood. He went to East Trigg Baptist Church to hear the gospel choirs. He wasn't a corporate suit trying to cash in; he was a poor kid from the projects who happened to have a photographic memory for every song he’d ever heard.

The beauty of That’s All Right Mama is that it feels like a collision. It’s the sound of a young man who didn't know the rules well enough to know he was breaking them. It lacked drums. Most people forget that. There is no drum kit on that record. The percussion you hear is just Bill Black slapping the wood of his bass and Elvis thumping the body of his guitar. It’s raw. It’s empty in all the right places.

🔗 Read more: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

Why Memphis Radio Went Crazy

When Sam Phillips took the acetate over to Dewey Phillips (no relation) at WHBQ, he didn't expect a revolution. Dewey played the song on his Red, Hot, and Blue show. The switchboard lit up. People were calling in, demanding to know who this singer was.

There was a problem, though. In 1954, audiences were segregated not just by law, but by sound. The callers thought Elvis was Black. They liked the song, but they were confused. Dewey called Elvis into the studio for an interview that night. He didn't ask him about his musical influences or his career goals. He asked him which high school he attended.

"Humes High," Elvis replied.

That was the "tell." Humes was an all-white school. In that one sentence, the audience realized this "Black-sounding" singer was actually a white boy from North Memphis. It was the bridge Sam Phillips had been looking for. He famously said if he could find a white man who had the Negro sound and the Negro feel, he could make a billion dollars. He found him.

The Technical "Mistakes" That Made the Record

If you analyze the recording of That’s All Right Mama, it’s technically "wrong" by 1954 standards. The slapback echo—that shimmering, ghostly sound—was a result of Sam Phillips running the tape through a second machine with a slight delay. It gave Elvis’s voice a nervous energy. It sounded like it was vibrating.

Scotty Moore’s guitar solo is also a bit of a mess, but a beautiful one. He’s trying to play a fingerstyle jazz lick but he’s doing it with the aggression of a country picker. The timing is loose. It breathes. If they had recorded this in a high-end studio in Nashville or New York, a producer would have polished away all the grit. They would have added a drum kit and a vocal chorus. They would have killed the magic.

💡 You might also like: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

Sun Studio was tiny. It was basically a converted radiator shop. The sound bounced off the walls and into the mics in a way that made everything feel immediate. When you listen to it today, even on a digital stream, you can still feel the air in the room. You can hear the surprise in Elvis’s voice when he realizes the song is actually working.

The Cultural Earthquake

You can't overstate how much this single track changed the world. Before That’s All Right Mama, "youth culture" didn't really exist as a commercial force. You were a child, and then you were an adult who dressed like your parents.

Elvis changed the uniform. He changed the rhythm. Most importantly, he changed the "vibe."

The B-side was a cover of Bill Monroe’s "Blue Moon of Kentucky." This was a sacred bluegrass anthem. Elvis turned it into a high-speed, stuttering pop song. Bill Monroe famously hated it at first, but then he saw the royalty checks and changed his mind. That pairing—a blues song on one side and a country song on the other—is the literal blueprint for rockabilly.

Critics at the time were horrified. They called it "vulgar." They said it was "jungle music." What they were actually afraid of was the blurring of racial lines. In a world of Jim Crow, a white kid singing "Black music" with that much conviction was a threat to the social order. That’s All Right Mama was the first crack in the dam.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Session

There’s a myth that Elvis walked into Sun Studio as a fully formed superstar. He wasn't. He was terrified. He was extremely polite, "yes sir" and "no sir" to a fault. He had tried to record a song for his mother’s birthday months earlier ("My Happiness"), and it was mediocre.

📖 Related: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

Sam Phillips almost gave up on him. The only reason they were there on July 5th was that Sam was trying to find a singer for a demo he’d received. Elvis wasn't even the first choice. He was just the local kid who kept hanging around the studio.

Another misconception is that the song was an instant national hit. It wasn't. It was a regional smash. It did well in Memphis, New Orleans, and parts of Texas. It took another year and a half, and a move to RCA Records, for Elvis to become a household name. But the DNA of everything he would ever do—the curled lip, the shaking leg, the vocal hiccups—is all present in those two minutes and two seconds of "That's All Right."

The Tragedy of Big Boy Crudup

While we celebrate Elvis, we have to look at what happened to Arthur Crudup. He never saw much of the wealth generated by the song. Despite the track becoming one of the most famous recordings in history, Crudup ended up working as a laborer and a bootlegger to make ends meet.

Elvis always gave him credit in interviews, calling him one of his favorite singers. But the systemic issues of the music industry in the 50s meant the songwriter was often the last person to get paid. Crudup reportedly said, "I realized I was a famous man and I was poor as a turkey." It’s a sobering reminder that the birth of rock and roll was built on the backs of artists who didn't always get their due.

How to Listen to "That’s All Right Mama" Today

To truly appreciate the song, you have to strip away the "Elvis as a caricature" image. Forget the jumpsuits. Forget the Vegas years. Forget the peanut butter and banana sandwiches.

- Listen to the breathing. Elvis is breathless. He’s excited. He’s rushing the lyrics because he’s caught in the moment.

- Focus on the bass. Listen to how Bill Black’s "slap" provides the heartbeat of the song. It’s more of a percussion instrument than a melodic one.

- Notice the lack of a chorus. The song is just a series of verses. It doesn't follow the standard pop formula. It’s just a groove that starts and stops.

- Compare it to 1954's Top 10. Listen to "Mr. Sandman" by The Chordettes or "Wanted" by Perry Como. Then play "That's All Right." The difference is staggering. It sounds like it’s from a different century.

Actionable Next Steps for Music Fans

If you want to understand the roots of what you’re listening to today, do a little "audio archaeology."

- Trace the line: Play Arthur Crudup’s 1946 original. Then play the Elvis version. Then play the Beatles’ live version from the BBC sessions. You can hear the evolution of the genre in real-time.

- Visit the site: If you’re ever in Memphis, go to Sun Studio. It’s still there. You can stand on the exact spot where Elvis stood. They have a little "X" on the floor. It’s surprisingly small. It makes you realize that you don't need a million-dollar budget to change the world. You just need a good idea and a little bit of nervous energy.

- Support the pioneers: Look into the Mt. Zion Memorial Fund. They work to provide headstones and recognition for blues artists who were buried in unmarked graves. It’s a small way to give back to the culture that gave us rock and roll.

Rock and roll wasn't invented by a committee. It wasn't designed in a boardroom. It was a mistake. It was a nineteen-year-old kid messing around on a break because he was tired of being told what to do. That’s All Right Mama remains the definitive proof that sometimes, the best things happen when you stop trying so hard and just play.