When you look at that famous picture of the observable universe, you aren't actually looking at a "photo" in the way you'd snap a selfie. It’s a map. Specifically, it is often a logarithmic visualization created by musicians and scientists like Pablo Carlos Budassi, or perhaps you're thinking of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) data from the Planck satellite. People get these confused all the time. One looks like a psychedelic iris; the other looks like a piece of moldy fruit.

Space is big. Really big. You just can't wrap your head around it.

The "observable" part of the universe is a sphere about 93 billion light-years across. If you’re wondering how it can be 93 billion light-years wide when the universe is only about 13.8 billion years old, you've hit on the first major headache of cosmology. Space is expanding. While the light was traveling toward us, the "stuff" it came from kept moving away. It’s like trying to run a marathon on a treadmill that keeps getting longer while you're running.

What that circular picture of the observable universe actually shows

Most people have seen the circular image where the Solar System is in the middle and the edge of the universe is the rim. That’s Budassi's map. It’s a masterpiece of data visualization, but it uses a logarithmic scale. If it were linear, the Sun would be a microscopic speck and the rest of the page would be empty blackness for miles.

By using logarithms, the artist can fit the Oort Cloud, the Kuiper Belt, Alpha Centauri, and the furthest reaches of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey all into one frame. It’s basically a cheat code for the human eye. You see the transition from our local "neighborhood" to the cosmic web—the large-scale structure where galaxies look like glowing threads of silk.

The light we can't see anymore

There is a hard limit to what we can see. It's called the particle horizon. Beyond that, the light simply hasn't had time to reach us since the Big Bang. But there's a catch. Because the universe is expanding at an accelerating rate (thanks, Dark Energy), some galaxies are moving away from us faster than the speed of light. They aren't "moving" through space faster than light; the space between us and them is stretching.

This means there are parts of the universe we will never see. They’ve slipped over the cosmic horizon. We are effectively in a shrinking bubble of "see-able" reality.

🔗 Read more: Why Browns Ferry Nuclear Station is Still the Workhorse of the South

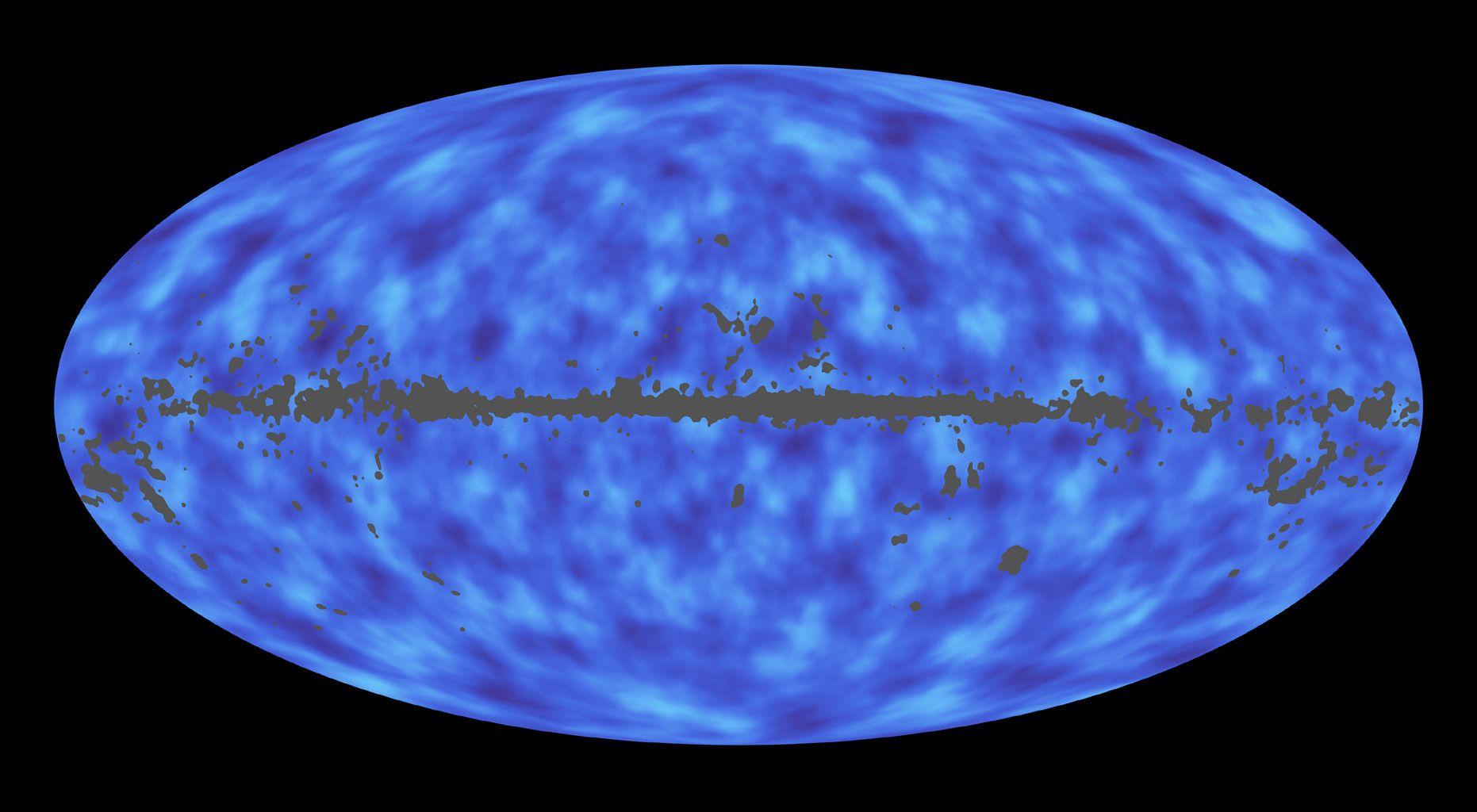

The CMB: The "Baby Picture" of everything

If you want the most scientifically accurate picture of the observable universe, you have to look at the Cosmic Microwave Background. This isn't a picture of stars. It’s a picture of heat. Specifically, it's the fossil radiation left over from roughly 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

Before this moment, the universe was a hot, dense soup of plasma. It was opaque. Photons—light particles—couldn't travel anywhere because they kept bumping into electrons. It was like trying to see through a thick fog. Then, the universe cooled down enough for atoms to form (the Recombination Era), the fog cleared, and light finally broke free.

The CMB map shows tiny temperature fluctuations. Blue spots are slightly cooler; red spots are slightly warmer. These tiny ripples are the seeds of everything. The cool spots had slightly more gravity, which pulled in more matter, which eventually became the galaxies, stars, and planets we have today. You are looking at the blueprint of the cosmos.

Why the colors look so weird

It's important to realize these aren't "colors" in the sense of a rainbow. The CMB is microwave radiation. It’s invisible to your eyes. We use "false color" to represent the data. If your eyes could see microwaves, the entire night sky would glow with a dull, uniform hum.

Common myths about the universe's "edge"

One of the biggest misconceptions about any picture of the observable universe is that it shows the "whole" universe. It doesn’t. It only shows the part we can see.

Think of it like being on a ship in the middle of the ocean at night. You can see as far as your lantern reaches. That’s your "observable ocean." But the ocean continues far beyond your light. We have no idea how big the actual universe is. It could be infinite. Or it could be shaped like a giant donut (a 3-torus).

💡 You might also like: Why Amazon Checkout Not Working Today Is Driving Everyone Crazy

- Myth: The universe has a center. (It doesn't. Every point looks like the center of its own observable bubble.)

- Myth: Galaxies are moving "away" from a central explosion. (Space itself is stretching everywhere at once.)

- Myth: The "edge" is a wall. (The edge is just a limit of time and light speed.)

The James Webb Factor

Lately, our "picture" of the universe has changed. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is looking further back than ever. It's seeing galaxies that shouldn't exist—at least not according to our old models. These "universe breakers" are massive galaxies that formed way too early.

Dr. Erica Nelson from the University of Colorado Boulder and her team found objects that look like red dots in the JWST data. These dots are actually massive galaxies from a time when the universe was only 3% of its current age. This is forcing cosmologists to rethink how fast stars can actually form.

When you look at a JWST Deep Field, every single smudge of light is a galaxy containing billions of stars. It’s a profound sense of scale that usually leads to an existential crisis. Or at least a very long walk.

How to actually "read" these images

If you’re looking at a Hubble or JWST image, remember the "Time Machine Effect." Because light takes time to travel, you are looking into the past.

- The Moon is 1.3 seconds ago.

- The Sun is 8 minutes ago.

- Andromeda is 2.5 million years ago.

- Those deep-field galaxies are 13 billion years ago.

You are never seeing the universe as it is right now. You are seeing a stacked history of everything that ever was.

Why this matters for you

Understanding the picture of the observable universe isn't just about cool wallpapers for your phone. It's about perspective. We live on a tiny rock orbiting a mid-sized star in the suburbs of a common spiral galaxy.

📖 Related: What Cloaking Actually Is and Why Google Still Hates It

But we’re also the only part of the universe (that we know of) that has figured out how to take its own picture. We are the cosmos experiencing itself. That’s a bit "woo-woo," but it’s factually true.

Actionable insights for the space enthusiast

If you want to go deeper than just looking at pretty pictures, here is how you can actually engage with the current state of cosmology:

- Use the ESASky tool. It’s a professional-grade web interface that lets you toggle between different wavelengths (X-ray, Infrared, Gamma) for any part of the sky. You can see the "invisible" universe for yourself.

- Download the "Cosmic Zoom" apps. There are several (like the classic 'Powers of Ten' concepts) that allow you to scroll from a proton to the observable limit. It helps fix the "scale" problem in your brain.

- Follow the Planck Mission archives. If you want the rawest data on the CMB, the European Space Agency (ESA) has public archives. It's dense, but it's the real deal.

- Look for "Gravitational Lensing." In deep field photos, look for warped, stretched-out galaxies that look like arcs. That’s gravity literally bending light, acting as a natural telescope. It’s one of the coolest proofs of Einstein’s General Relativity.

- Check the "Astronomy Picture of the Day" (APOD). NASA has been running this since the 90s. It’s still the best place for verified, expert-explained imagery without the clickbait.

The universe is expanding. The pictures are getting better. Our understanding is currently in a state of flux because of the JWST data. It's a weird, great time to be looking up.

Stop thinking of the universe as a place where things happen. The universe is the thing that is happening.

Next Steps for Exploration:

Start by exploring the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) interactive maps. They provide a 3D fly-through of the local universe that replaces the flat "circle" map with actual depth data. Once you've mastered the local structures like the Laniakea Supercluster, look into the JWST Cycle 2 and 3 release schedules to see when the next "deepest ever" images are slated for public viewing. This allows you to stay ahead of the news cycle and understand the context of the "new" galaxies being discovered in the early universe.