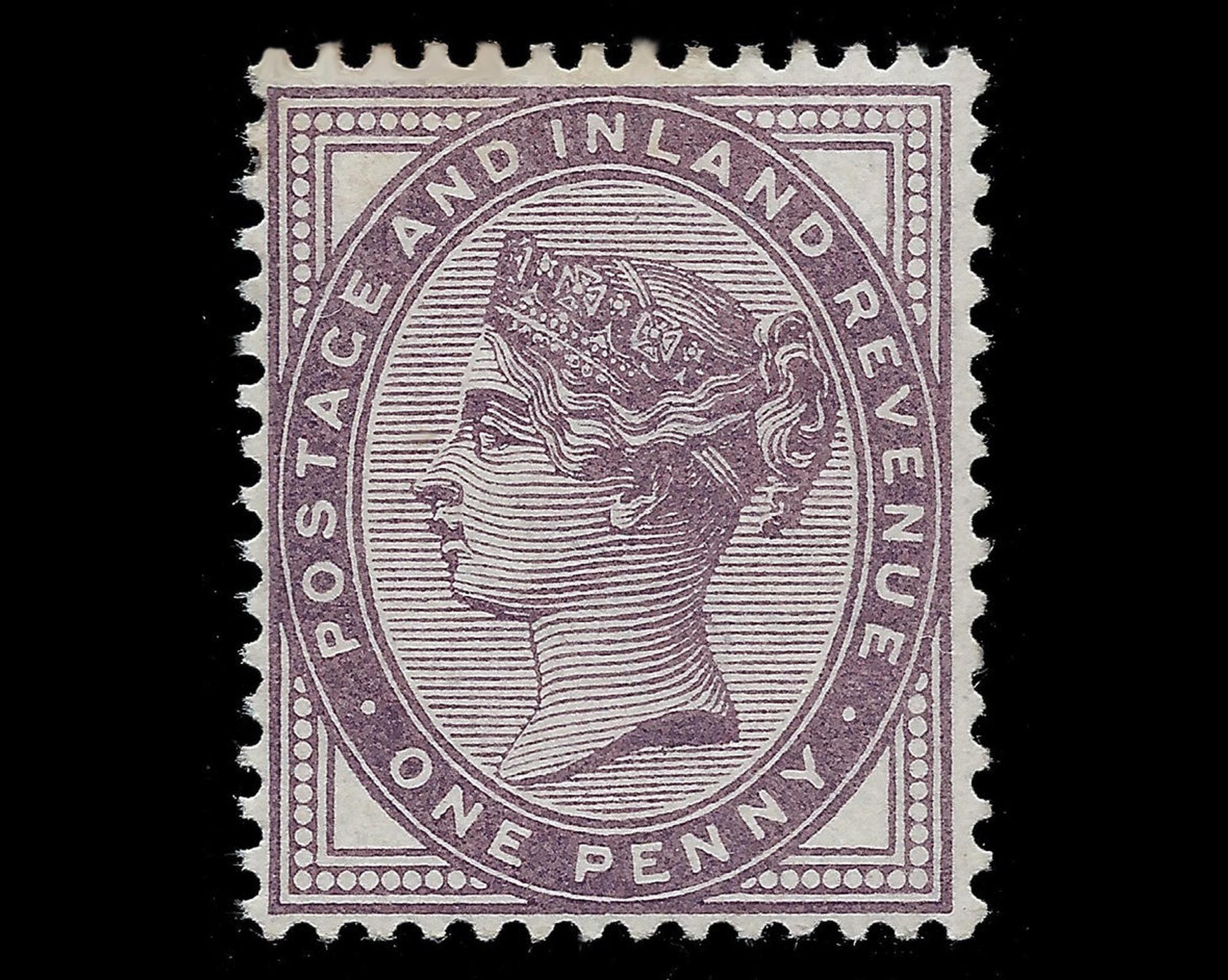

You’ve probably seen it. Maybe you were digging through a dusty shoebox of your grandfather’s old letters or flipping through a bargain bin at a flea market. There it is: a small, rectangular piece of paper, usually lilac or red, staring back at you with the stoic profile of Queen Victoria or King Edward VII. It says postage and inland revenue one penny.

It looks important. It looks old. It looks like it should be worth a fortune.

But here’s the reality that most hobbyists don't want to hear. These stamps were the workhorses of the British Empire. They were everywhere. Billions were printed. Honestly, if you have one, there is a 99% chance it’s worth about as much as the paper it's printed on. But—and this is a big "but"—that remaining 1% is where things get wild. Understanding the difference between a common scrap of paper and a genuine philatelic treasure requires a bit of detective work.

What actually is a Postage and Inland Revenue One Penny stamp?

Back in the day, the British government realized they were being inefficient. Before 1881, if you wanted to mail a letter, you used a postage stamp. If you needed to pay a tax on a legal document, like a receipt or a contract, you had to buy a separate revenue stamp. It was a clunky system. People hated carrying two different types of stamps.

The Customs and Inland Revenue Act of 1881 changed the game. It allowed a single stamp to be used for both purposes. This gave birth to the postage and inland revenue one penny stamp, specifically the iconic "Penny Lilac."

It wasn't just about convenience. It was about security. The lilac ink was "fugitive," which is a fancy way of saying it would wash away if someone tried to clean off a cancellation mark to reuse the stamp. People were crafty back then. The government had to stay one step ahead of the fraudsters.

The Penny Lilac became the most widely used stamp in the world at the time. Between 1881 and 1901, about 33.6 billion of them were printed. Read that number again. 33.6 billion. That is why they are so common today. If you find one in a drawer, you aren't looking at a rare artifact; you're looking at the 19th-century equivalent of a discarded gum wrapper.

Why some versions are worth a second look

Even though the bulk of these are common, collectors lose their minds over the tiny details. This is where the nuance of philately comes in.

🔗 Read more: God Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: The True Story Behind the Phrase Most People Get Wrong

Take the "14 Dots" vs. "16 Dots" issue.

Look at the corners of a Queen Victoria Penny Lilac. There are little white dots in the circular frame surrounding her head. In the first printings (Die I), there were 14 dots in each corner. Shortly after, they changed the design (Die II) to have 16 dots.

Why does this matter?

Because the 14-dot version was only in production for a few months. It's significantly scarcer. If you have a mint condition 14-dot Penny Lilac, you're looking at something worth maybe £30 to £50. If it's the 16-dot version? You're lucky to get 50p.

The King Edward VII versions

When Victoria passed away, her son Edward VII took the throne. The postage and inland revenue one penny design shifted. Now we’re talking about the "Penny Red" or "De La Rue" printings. These stamps are gorgeous, usually a deep scarlet or carmine.

With the Edwardian stamps, the money is in the "Specimen" overprints or the specific shades of ink. Experts like those at Stanley Gibbons look for things like "Bright Carmine" versus "Pale Scarlet." To a normal person, they look identical. To a specialist, the difference is hundreds of dollars.

Then there are the "inverted watermarks." If you hold the stamp up to the light or dip it in watermark fluid (don't do this unless you know what you're doing), you might see a crown symbol. If that crown is upside down, you’ve just hit a mini-jackpot.

💡 You might also like: Kiko Japanese Restaurant Plantation: Why This Local Spot Still Wins the Sushi Game

The Inland Revenue "Overprints" are the real prize

Now, let's talk about the stuff that actually makes headlines. Sometimes, these standard stamps were overprinted with the words "I.R. Official."

These were for use by the Inland Revenue department itself. They aren't standard postage and inland revenue one penny stamps sold to the public. They were government property.

The 1904 6d (sixpence) version of this series is one of the rarest stamps in British history, often dubbed the "Irving Block" or similar names depending on the collection. While the one-penny version of the I.R. Official overprint isn't as legendary as the sixpence, it is still worth significantly more than the standard version.

Collectors hunt for:

- Clear, crisp overprints that aren't forged.

- Stamps that were actually used on "Official" mail.

- Errors where the overprint is missing a letter or is shifted.

Common misconceptions that mislead beginners

I see this all the time on eBay. Someone lists a beat-up, torn, heavily canceled Penny Lilac for $500. They think because it's from the 1880s, it must be valuable.

It's not.

Condition is everything. In the world of the postage and inland revenue one penny, a single missing "perf" (one of those little teeth on the edge) can tank the value by 90%. If the stamp has a heavy black ink smudge across the Queen's face, most serious collectors won't even touch it.

📖 Related: Green Emerald Day Massage: Why Your Body Actually Needs This Specific Therapy

You also have to watch out for "re-gummed" stamps. Some dishonest sellers take a used stamp, wash off the cancellation, and add fake glue to the back to make it look "Mint Never Hinged." It’s a scam as old as the hobby itself.

Real expertise comes from feeling the paper and knowing the specific shade of "Lilac" that was used in 1884 versus 1888. It's a level of obsession that borders on the scientific.

How to check if your stamp is actually valuable

If you’re staring at a postage and inland revenue one penny right now, do these three things:

First, count the dots. If it's a Queen Victoria lilac and you see 14 dots in the corners instead of 16, put it in a protective sleeve immediately. You have something interesting.

Second, check the back. Is there a watermark? Is it a crown? Is it the right way up? An inverted watermark on a standard penny stamp can turn a 10-cent item into a $50 item.

Third, look for "Specimen" or "I.R. Official" stamps. These are the "Official" overprints that carry the real weight in the market.

Don't get your hopes up too high. Most of these stamps were used to pay for receipts in shops or to mail mundane postcards. They were the "forever stamps" of their era. But every now and then, a rare plate number or a printing error slips through the cracks.

Actionable steps for the budding collector

If you think you've found something special, don't go to eBay first.

- Get a magnifying glass. You need at least 10x magnification to see the plate details and the condition of the paper fibers.

- Buy a basic Stanley Gibbons Great Britain Concise Catalogue. It is the gold standard. It will show you the exact price differences between the shades of lilac and red.

- Visit a local stamp club. Philatelists are generally a friendly bunch. They love showing off their knowledge and will tell you in five seconds if your stamp is a gem or a dud.

- Preserve it. If the stamp is still on the original envelope (the "cover"), do not soak it off. Stamps are often worth more when they are attached to the original letter, as the postmark provides proof of date and location, which can add historical "postal history" value.

The postage and inland revenue one penny is a tiny window into the Victorian bureaucracy. It's a piece of history you can hold in your tweezers. Even if yours isn't worth a million dollars, it’s a direct link to a world where a letter was the only way to talk to someone across the country. That, in itself, is worth something.