You’ve seen it a thousand times. A grainy pic of a coral snake pops up on your Facebook feed or a local hiking group, usually accompanied by a frantic warning about the "deadly" serpent found in someone's backyard. Everyone in the comments starts reciting the rhyme. You know the one. "Red touch yellow, kill a fellow; red touch black, friend of Jack." It's basically the first thing we learn about snakes if we grow up in the American South or Southwest.

But here’s the thing: that rhyme is kinda trash.

If you are relying on a catchy poem to decide whether or not to grab a shovel or run for your life, you’re playing a dangerous game with biology. Nature doesn't always follow the rules we make up for it. In fact, if you’re looking at a pic of a coral snake from anywhere south of Mexico City, that rhyme could actually get you bitten.

Why Your "Red on Yellow" Knowledge is Incomplete

The North American Coral Snake (Micrurus fulvius) is a beautiful, shy, and incredibly misunderstood creature. It’s small. It’s colorful. It looks like a toy. Because they belong to the family Elapidae—the same family as cobras and mambas—they possess a potent neurotoxic venom.

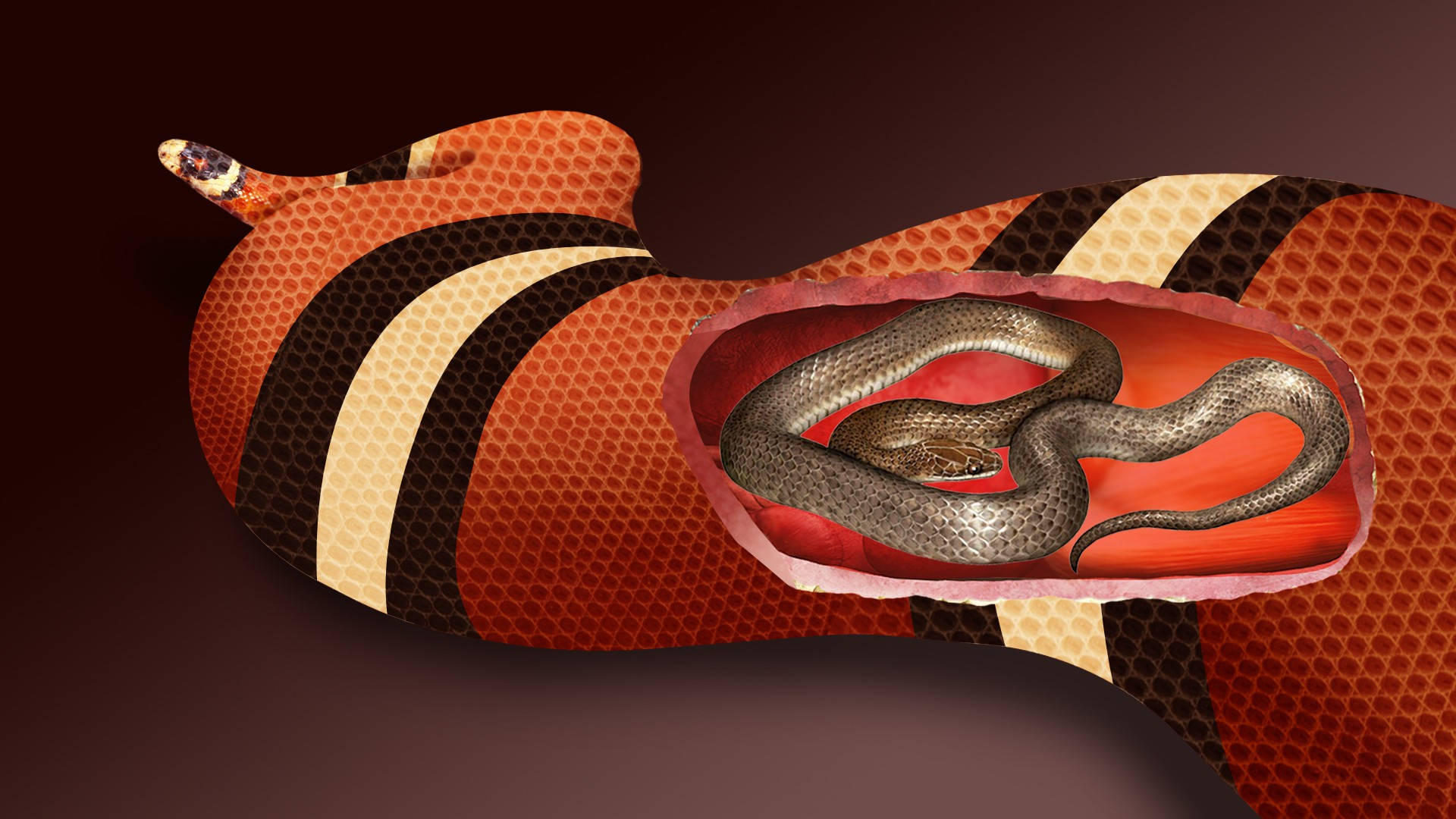

When people search for a pic of a coral snake, they are usually trying to differentiate it from the Scarlet Kingsnake or the Milk Snake. These mimics have evolved to look almost exactly like the venomous version to scare off predators. It’s called Batesian mimicry. Basically, the harmless snake is "catfishing" the rest of the animal kingdom.

In the United States, the "red on yellow" rule generally holds up. If the red bands touch the thin yellow bands, it’s a coral snake. If the red bands touch the black bands, it’s a non-venomous mimic. Easy, right?

Not really.

Aberrant patterns happen. Sometimes, a coral snake is born melanistic (almost all black) or erythristic (mostly red). There are documented cases of "monochrome" coral snakes that lack yellow pigment entirely. If you see a weirdly colored snake and think, "Well, the red isn't touching yellow," and decide to pick it up, you might be in for a very bad day.

The "South of the Border" Problem

If you travel to Central or South America, throw the rhyme in the garbage. Seriously.

👉 See also: Barn Owl at Night: Why These Silent Hunters Are Creepier (and Cooler) Than You Think

In those regions, there are dozens of species of coral snakes. Some have red touching black. Some have no yellow at all. Some are just bicolor. Experts like Dr. Jonathan Campbell, who has spent decades studying herpetology in the neotropics, frequently point out that the color patterns in the tropics are so diverse that "the rhyme" is a death trap.

Analyzing a Real Pic of a Coral Snake: Beyond the Colors

If you're looking at a photo and trying to ID it, stop looking at the stripes for a second. Look at the head.

Coral snakes have very blunt, rounded heads. They don’t have the classic "triangular" head that people associate with pit vipers like Rattlesnakes or Copperheads. This is a common point of confusion. People think "triangular head equals venomous," but coral snakes break that rule. Their heads are usually black from the tip of the nose to just behind the eyes.

Then, check the eyes.

A coral snake has round pupils. Most people are taught that venomous snakes have slit-like "cat eyes." Again, that only applies to vipers. Coral snakes are elapids. Their round pupils make them look "cute" or "harmless" compared to a grumpy-looking Rattlesnake, which is exactly why so many people accidentally handle them.

Behavioral Clues You Can't See in a Still Photo

A pic of a coral snake rarely captures how they move. They are fossorial. That’s a fancy way of saying they like to dig. They spend the vast majority of their lives under leaf litter, logs, or underground.

Unlike a Racer or a Ribbon Snake that might zip away the second they see you, a coral snake is often slow and methodical. When threatened, they do something weird: they curl their tail into a little spiral and "pop" their cloaca (basically a snake fart) to startle you. It's a defensive display intended to draw your attention away from their head.

The Reality of the "Deadly" Bite

Let's get one thing straight: nobody is dying from coral snake bites anymore.

✨ Don't miss: Baba au Rhum Recipe: Why Most Home Bakers Fail at This French Classic

Since the development of antivenom, fatalities in the United States have plummeted to near zero. The last recorded death from a native coral snake in the U.S. was in 2006, and that was a very specific, tragic case where the person did not seek medical attention.

The venom is serious, though. It’s a neurotoxin. Unlike the hemotoxic venom of a Copperhead, which causes localized swelling, tissue death, and excruciating pain, coral snake venom goes for the nervous system.

It stops your brain from talking to your muscles.

Initially, a bite might not even hurt that much. There might be little to no swelling. But hours later, you could start experiencing slurred speech, double vision, and eventually, respiratory failure. Your diaphragm just forgets how to breathe.

The Antivenom Crisis

Here is a bit of niche trivia that most people don't know: for a long time, we were running out of coral snake antivenom.

The primary antivenom, Micrurus fulvius Antivenin, was produced by Wyeth (now owned by Pfizer). They stopped making it in the early 2000s because it wasn't profitable. Coral snake bites are rare—maybe 100 a year in the U.S.—compared to thousands of pit viper bites.

For years, the FDA kept extending the expiration dates on the existing stock because there was no replacement. Thankfully, new production and alternative options like "Coralmyn" from Mexico have helped bridge the gap, but it remains a specialized and expensive treatment.

How to Take a Safe Pic of a Coral Snake

If you stumble upon one of these beauties, you’re actually very lucky. They are reclusive. Seeing one in the wild is a treat for any nature lover.

🔗 Read more: Aussie Oi Oi Oi: How One Chant Became Australia's Unofficial National Anthem

- Keep your distance. Use the zoom on your phone. You don't need to be three inches away to get a "good" pic of a coral snake.

- Don't pin it. Never try to hold the snake down with a stick to get a better angle. This is when most bites happen.

- Watch your step. If you see one, there might be another nearby, or you might be standing in a spot where it’s trying to hide.

- No "Hero" shots. Don't be that guy trying to hold it by the tail for an Instagram post.

Coral snakes have small, fixed fangs. They don't have the long, folding fangs of a Rattlesnake. To deliver a full dose of venom, they generally need to "chew" a bit. However, this doesn't mean they can't "dry bite" or deliver a quick, effective strike. Any contact is a bad idea.

Common Misconceptions Found in Online Photos

When you search for a pic of a coral snake, you'll often see photos of the "Long-nosed Snake" or the "Ground Snake." These guys are the ultimate imposters.

The Long-nosed snake (Rhinocheilus lecontei) even has the red, black, and creamy-yellow colors, but its snout is—you guessed it—long and upturned. It’s a specialized lizard-eater and completely harmless.

Then there’s the Shovel-nosed snake. In the Mojave desert, these guys look incredibly similar to coral snakes at a glance. But if you look closely at the belly, coral snakes have bands that go all the way around their body like a candy cane. Most mimics have a solid-colored or checkered belly.

Pro tip: If you have to flip a snake over to check its belly to see if it’s venomous, you’ve already messed up. Just leave it alone.

Actionable Steps for Snake Encounters

If you find yourself staring at a colorful snake in your yard and you aren't sure what it is, follow these steps instead of trying to remember a nursery rhyme:

- Take a photo from 5 feet away. Most modern smartphones have incredible digital zoom. You can get a clear enough shot for identification without entering the "strike zone."

- Upload to iNaturalist or a dedicated FB ID group. There are groups like "Snake Identification" on Facebook where actual herpetologists respond within minutes. They don't use rhymes; they look at scale counts, loreal scales, and ocular arrangements.

- Give it an exit. Most snakes are just passing through. If you leave it alone, it will likely be gone in an hour.

- Wear shoes in the garden. This sounds basic, but many bites occur when people reach into leaf litter with bare hands or walk through tall grass in flip-flops.

- Check your local hospital. If you live in a known coral snake habitat (Florida, Texas, Arizona, etc.), it doesn't hurt to know which local Level 1 trauma centers carry specialized antivenom.

Honestly, the best way to appreciate a coral snake is through a lens. They are vital parts of the ecosystem, keeping other snake populations in check (yes, they eat other snakes!). By understanding the nuance of their biology rather than relying on oversimplified rhymes, you can coexist with these vibrant neighbors without the drama.

Understand that nature is rarely "standardized." Colors fade, mutations happen, and geography changes everything. Treat every colorful, banded snake with the respect you'd give a venomous one, and you'll never have to worry about whether Jack is your friend or not.