It’s a heart-sink moment. You open your mailbox or your inbox, and there it is: a notice of money owed NYT. At first, you think it’s a scam. Honestly, who mails a physical bill for a digital newspaper in 2026? But then you look closer. The branding is right. The account number matches that old subscription you thought you cancelled during a frantic "clean up my life" phase three years ago. It’s annoying. It feels predatory. But more often than not, it’s a legitimate result of how The New York Times handles its billing cycles and customer retention strategies.

Getting a bill from a media giant when you aren't even reading the paper is a special kind of frustration. You’re busy. You’ve got Netflix, Spotify, a gym membership you never use, and now a legacy news outlet is knocking on your door for thirty-six bucks and change.

The reality is that "zombie subscriptions" are the lifeblood of modern media revenue. Companies like The New York Times Company (NYT) rely heavily on auto-renewals. If your credit card on file expires, they don't always just cut you off. Sometimes, they keep the service running and the tab moving. Then, they send the bill.

Why You’re Getting a Notice of Money Owed NYT Now

The "Notice of Money Owed" usually triggers when a specific set of circumstances occurs. Most people assume that if a payment fails, the service stops. That’s how it works with a pre-paid coffee card or a burner phone. It’s not how it works with a "continuous service" contract. When you signed up—probably for that $1-a-week teaser rate—you agreed to a terms-of-service agreement that essentially says: "We will keep charging you until you tell us to stop."

If your credit card expired or you issued a chargeback, the NYT billing system doesn't necessarily see that as a cancellation. It sees it as a "delinquent account." They continue to provide access to the digital site or deliver the physical paper, and the debt accumulates. Eventually, their accounting department moves the balance from "active" to "past due," and the formal notice goes out.

It’s a legacy business move.

Wait. Why now? Usually, these notices go out in batches. If the Times is cleaning up its balance sheet for a quarterly earnings report, they might get aggressive about collecting small balances that have been sitting there for months. It’s also common to see these after a promotional period ends. You forgot the price jumped from $4 to $25 a month. Your card blocked the larger-than-usual transaction. Now, you’ve got a balance.

The Role of Northland Group and Third-Party Collections

Sometimes the notice of money owed NYT doesn't come on a gray New York Times letterhead. It comes from a third party. Over the years, subscribers have reported receiving letters from agencies like Northland Group or similar debt collectors.

💡 You might also like: Wegmans Meat Seafood Theft: Why Ribeyes and Lobster Are Disappearing

This is where it gets scary for people.

"Is this going to hit my credit score?" That’s the first question everyone asks. Generally, for small amounts like a newspaper subscription (usually under $100), major credit bureaus like Equifax and Experian don't always see these reported. However, that doesn't mean it’s impossible. If the debt is sold to a collection agency, it becomes a formal "collection account."

You have to be careful here. Don't just ignore it. If a collection agency is involved, they bought your debt for pennies on the dollar and are highly motivated to get the full amount from you.

Decoding the Terms of Service

You probably didn't read the fine print. Nobody does. But if you look at the NYT Subscription Terms, they are very clear about "Automatic Renewal."

- Your subscription continues indefinitely.

- The Times reserves the right to change rates with notice.

- Cancellation only happens when you follow their specific steps.

If you just deleted the app and thought, "That's that," you're legally still on the hook. It’s a "negative option" billing model. It’s controversial, and the FTC has been looking into making "click-to-cancel" a federal requirement to stop exactly this kind of "notice of money owed" surprise.

The "I Already Cancelled" Dilemma

This is the most common complaint. You called. You chatted with a bot. You sent an email. Yet, three months later, the notice of money owed NYT arrives anyway.

The Times has historically been criticized for its "retention" tactics. For a long time, you could sign up online in three clicks, but you had to call a human being during Eastern Standard Time business hours to cancel. They’ve improved this—mostly due to California’s strict consumer protection laws—but glitches happen.

📖 Related: Modern Office Furniture Design: What Most People Get Wrong About Productivity

If you have a confirmation number from a previous cancellation, you are gold. If you don't, you're in a "he-said, she-said" battle with a multi-billion dollar corporation.

How to Handle the Notice Without Losing Your Mind

Don't panic. Seriously.

First, verify the debt. Log into the official NYT website—don't click links in a suspicious email—and check your account status. If the balance is there, it's real. If the website says your balance is $0 but you have a letter, you might be looking at a phishing scam. Scammers love using the names of big brands like the NYT or Netflix to scare people into clicking "Pay Now" links.

If the debt is legitimate but you truly thought you cancelled, call their customer service.

Be polite but firm.

Explain that you haven't accessed the account since [Date]. Most of the time, the representative has the power to waive "past due" balances to keep your goodwill, especially if you hint that you might subscribe again in the future. They want subscribers, not enemies.

What if it's already with a debt collector?

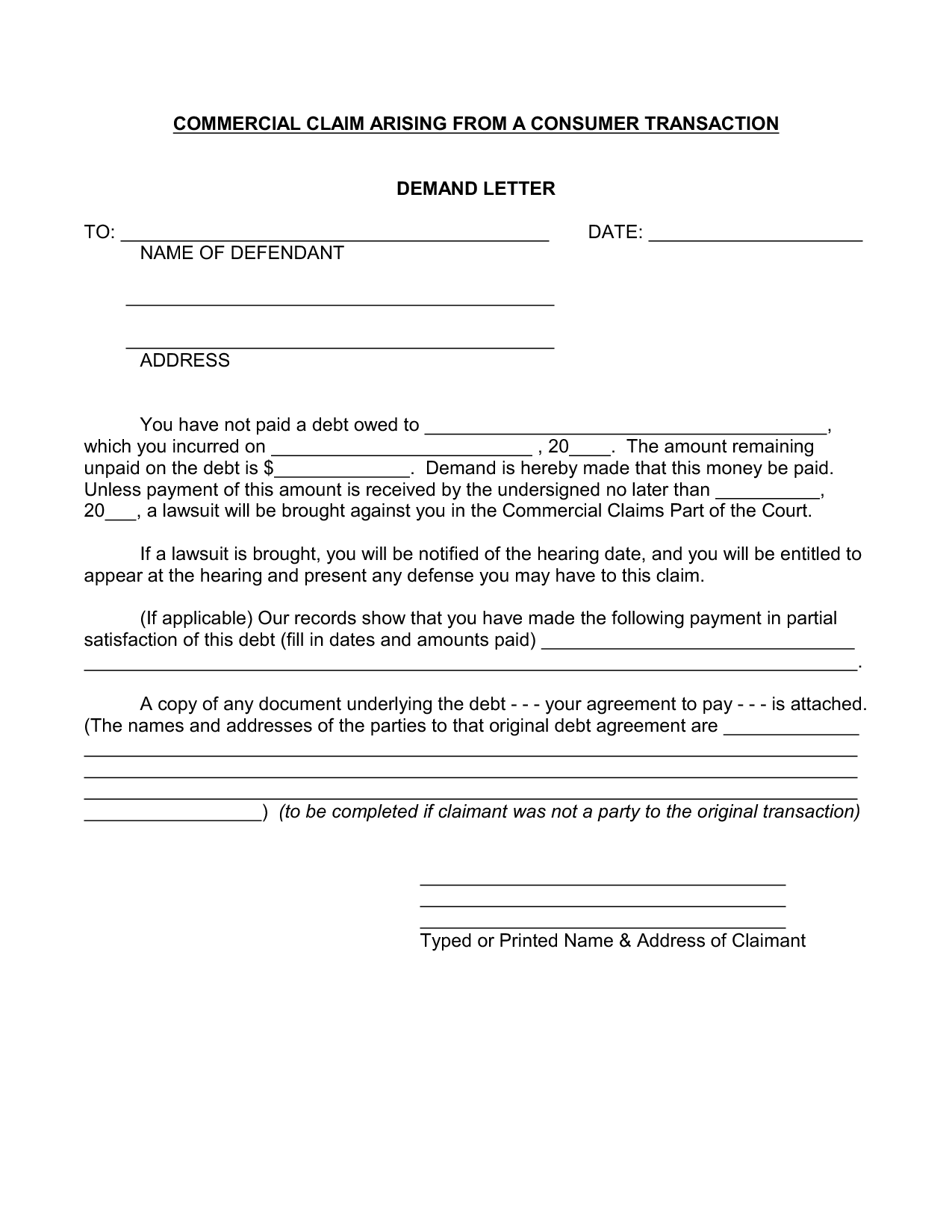

If Northland Group or another agency has the debt, the game changes. You need to:

👉 See also: US Stock Futures Now: Why the Market is Ignoring the Noise

- Request a Debt Validation Letter. They are legally required to prove you owe the money under the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA).

- Check your records. Find that cancellation email. Even a screenshot of your browser history showing you visited the "cancel" page can help.

- Offer a settlement. If you owe $60, offer $20 to "delete" the record. This is often called a "pay for delete" agreement, though they aren't always required to honor the "delete" part.

Actionable Steps to Clear Your Name

If you are staring at a notice of money owed NYT, here is your immediate checklist to resolve it and protect your credit.

Verify the Source

Check the return address. A real notice will come from The New York Times or a recognized agency. Look for your specific account ID. If the letter asks you to pay via gift cards or Bitcoin, it is a scam. 100%. Throw it away.

Audit Your Access

Go to your browser history. If you haven't logged into NYTimes.com in six months, you have a strong argument for "non-usage." While the terms of service say you owe regardless of usage, a manager will often zero out the balance if you can prove you weren't actually consuming the product.

The "California Rule" Strategy

If you live in California, or even if you don't, mention California’s Automatic Renewal Law (ARL). It’s one of the strictest in the country. It requires companies to provide an easy, online way to cancel. If the NYT made it difficult for you to cancel, mentioning that you’re aware of consumer protection standards often speeds up a resolution.

Document Everything

If you talk to someone, get their name and a reference number. If you pay the balance, keep the receipt. You don't want to get a second notice for the same money three months from now because their database didn't sync correctly.

Update Your Payment Methods

To prevent this from happening again with other services, consider using a virtual credit card service like Privacy.com. You can set a "spend limit" or make the card "single-use." If the price jumps or they try to charge you after a cancellation, the transaction simply fails, and you never have to deal with a "notice of money owed" ever again.

Handling this is mostly about persistence. It’s a "paperwork" problem, not a "you're a bad person" problem. The Times sends out thousands of these. Resolving it usually takes one focused phone call or a very sternly worded email to their billing department. Just make sure you get a confirmation in writing that the "balance is resolved" before you hang up. That piece of paper is your shield.

Once that’s done, you can go back to reading the news—perhaps with a library card this time.