Space is big. Really big. But it’s also remarkably dark and empty, which makes finding a clear, high-resolution image of Kuiper Belt objects a nightmare for even the best telescopes we’ve got. Most people see a glowing, crowded ring of ice and rock in their mind’s eye. They imagine a dense field of debris encircling our solar system like a thick donut. Honestly? It's nothing like that. If you were standing on a rock out there, you wouldn't even see your nearest neighbor with the naked eye. It’s a ghost town of frozen leftovers from the birth of our solar system, sitting way out past Neptune.

We’re talking about a region that starts at roughly 30 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun and stretches out to about 50 AU. To put that in perspective, one AU is the distance from Earth to the Sun. It’s far. So far that the sunlight hitting these objects is about 1,000 times fainter than what we get on a sunny day at the beach. When you look at an image of Kuiper Belt targets like Arrokoth or Pluto, you aren't seeing a snapshot taken with a Kodak camera. You’re seeing the result of billions of dollars in technology, years of travel, and some of the most complex "long-exposure" math ever conceived by humans.

Why Real Kuiper Belt Images Are So Hard to Get

Try taking a photo of a charcoal briquette in a dark room from a mile away. That’s basically the challenge NASA faces. Most of the "images" you see online are actually artist's impressions. They’re gorgeous, sure. They have dramatic lighting and swirling mists. But they aren't real. The real ones? They’re usually just tiny, pixelated white dots moving against a sea of black.

It’s all about the "inverse square law." Basically, light has to travel from the Sun out to the Kuiper Belt, bounce off a cold rock, and then travel all the way back to our telescopes near Earth. By the time that light gets back to us, there’s almost nothing left of it. This is why the image of Kuiper Belt objects captured by the New Horizons spacecraft changed everything. It didn't wait for the light to come to it; it went to the source.

When New Horizons flew past Pluto in 2015, we finally saw what a Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) actually looks like. It wasn't a dead, cratered moon. It had giant glaciers of nitrogen ice, blue skies, and mountains made of water ice that are as tall as the Rockies. This shattered the idea that the outer solar system was just a boring graveyard. It's geologically alive. Sorta.

The Arrokoth Breakthrough

In 2019, New Horizons gave us something even more bizarre: an image of Kuiper Belt object 486958 Arrokoth. It looked like a red snowman. Or a ginger snap.

✨ Don't miss: The Portable Monitor Extender for Laptop: Why Most People Choose the Wrong One

Scientists were obsessed. Why? Because Arrokoth is a "contact binary." Two separate spheres gently drifted together at walking speed and just... stuck. This tells us a lot about how planets form. It wasn't a violent, smash-and-grab collision. It was a slow dance in the dark. If the Kuiper Belt were as crowded as the movies suggest, Arrokoth would have been smashed to bits eons ago. Instead, it’s been sitting there, pristine and frozen, for 4.5 billion years. It’s a time capsule.

The Tech Behind the Lens

We don't just use visible light. That would be useless. To get a decent image of Kuiper Belt territory, astronomers use a mix of infrared sensors and occultation.

Occultation is a fancy word for "watching a star blink." Since KBOs are too small and dark to see directly most of the time, we watch them pass in front of distant stars. When the star blinks out, we can calculate the size and shape of the object. It’s like trying to figure out the shape of a bird by looking at its shadow on a wall at midnight.

- The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is the current king of this. Because it looks in infrared, it can see the heat—tiny as it is—radiating from these frozen worlds.

- Ground-based surveys like the Vera C. Rubin Observatory (which is coming online soon) will use massive cameras to map the sky repeatedly, catching the movement of these "slow-mo" rocks.

- Then there's the "stacking" method. Digital cameras take hundreds of shots and layer them on top of each other to bring out the faint signal of a KBO against the background noise of space.

Pluto Is Only the Beginning

Pluto is the celebrity of the Kuiper Belt, but it’s an outlier. Most KBOs are much smaller. We call them "cold classicals." They have orbits that are almost perfect circles and they haven't been messed with since the solar system was a baby.

When you look at a high-res image of Kuiper Belt inhabitants like Haumea, you see something shaped like a football. Why? It spins so fast that it stretched itself out. It even has rings. Or look at Makemake, which is covered in frozen methane and ethane. These worlds are weird. They defy the "rules" we learned from looking at the inner planets like Mars or Venus.

🔗 Read more: Silicon Valley on US Map: Where the Tech Magic Actually Happens

The colors are a big deal too. A lot of these objects are red. Not "Mars red," but more like a deep, rusty brownish-red. This comes from tholins. Tholins are organic compounds that form when ultraviolet light hits simple molecules like methane. Basically, space radiation is "baking" the surfaces of these ice worlds and turning them into organic sludge. It’s the raw ingredients for life, just kept in a deep freezer at -400 degrees Fahrenheit.

Misconceptions That Just Won't Die

You've probably seen those posters where the Kuiper Belt looks like an asteroid belt on steroids. Total myth.

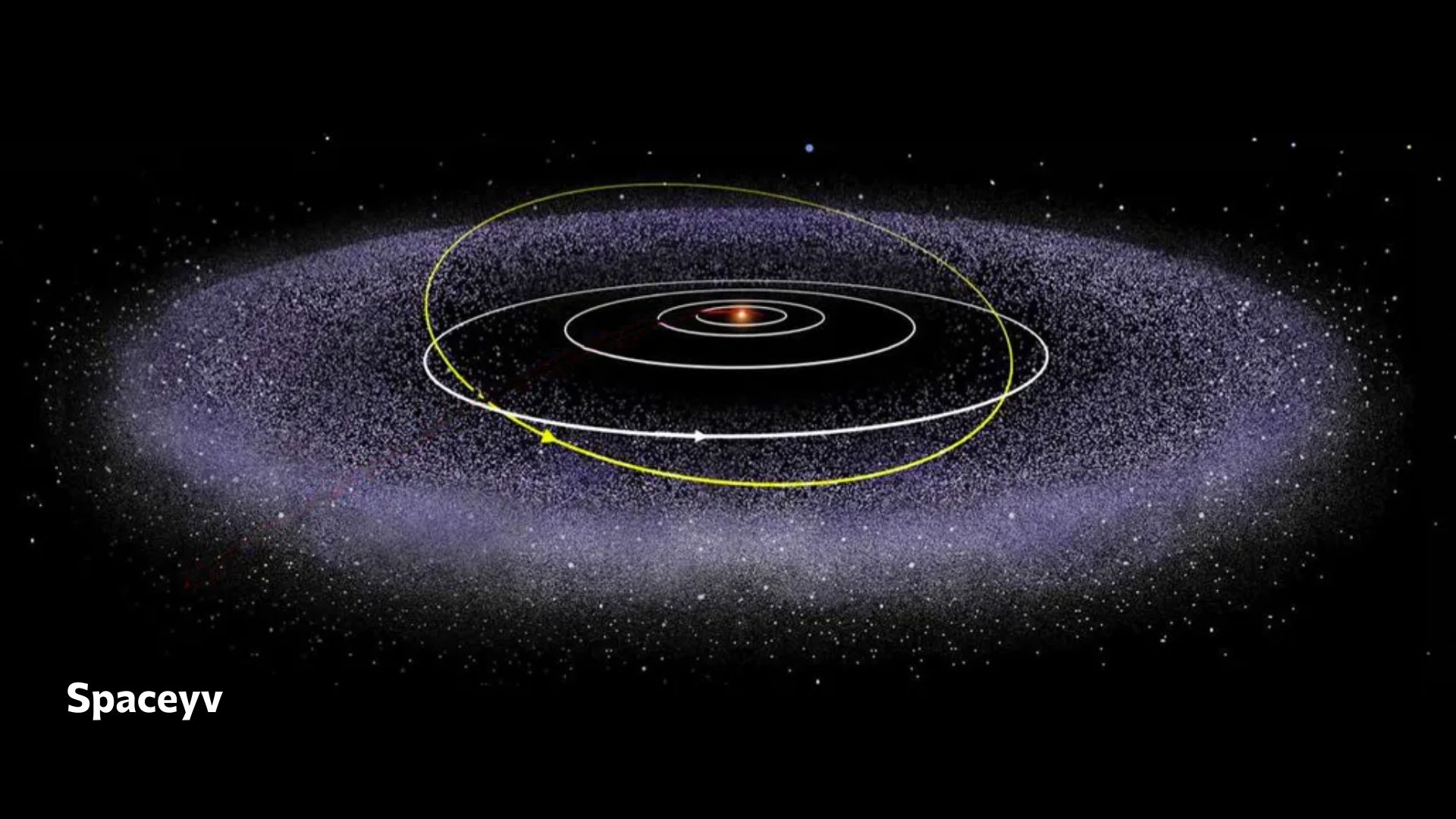

The Kuiper Belt is actually about 20 times as wide and 20 to 200 times as massive as the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. But it's also spread out over a vastly larger volume of space. If you were flying through it in a spaceship, you’d have to try really hard to hit something.

Also, don't confuse it with the Oort Cloud. That’s a common mistake. The Kuiper Belt is a relatively flat disk. The Oort Cloud is a giant spherical shell that's way, way further out—like, thousands of times further. We don't have a single direct image of Kuiper Belt's distant cousin, the Oort Cloud, because it’s basically at the edge of interstellar space.

How to Find Real Images Yourself

If you want to see the real deal, don't just Google "cool space pictures." You’ll get a bunch of AI-generated junk or Photoshop art. Go to the sources.

💡 You might also like: Finding the Best Wallpaper 4k for PC Without Getting Scammed

- NASA’s Planetary Data System (PDS): This is where the raw files live. They aren't pretty. They're black and white and grainy. But they are real.

- The New Horizons Mission Gallery: This is the gold standard for image of Kuiper Belt objects. Look for the "LORRI" instrument images. LORRI is essentially a high-powered telescope strapped to a piano-sized spacecraft.

- Hubble’s Outer Solar System Surveys: Hubble is old, but it still has a "sharp" eye for spotting faint KBOs that ground telescopes miss.

It’s easy to feel a bit let down when a "real" image is just a blurry blob. But think about what that blob represents. It’s a piece of the puzzle of where we came from. Every pixel is a mountain of ice or a crater that hasn't changed since before the dinosaurs existed.

Future Missions: What's Next?

We’re currently in a bit of a waiting game. New Horizons is still screaming through space, but it’s running out of fuel and targets. There are talks of a "dedicated" Kuiper Belt mission, something that could orbit one of these worlds rather than just flying by at 30,000 miles per hour.

Technological leaps in "Light Sails" might be the answer. Instead of heavy chemical rockets, we could send tiny, camera-equipped probes pushed by lasers. They could reach the Kuiper Belt in a fraction of the time it took New Horizons. Imagine getting a 4K image of Kuiper Belt objects from a dozen different worlds in a single decade. That’s the dream.

Actionable Insights for Space Enthusiasts

If you're fascinated by the edge of the solar system, don't just be a passive consumer of images. Use these steps to dive deeper:

- Check the "Raw" Feeds: Follow the New Horizons raw image feed. Seeing the unedited data helps you appreciate how much work goes into the final "colorized" versions NASA releases.

- Use Citizen Science: Join projects like "Backyard Worlds: Planet 9" on Zooniverse. You can actually help professional astronomers look through telescope data to find new KBOs. People have discovered entire new worlds this way from their laptops.

- Learn to Spot the Fakes: If an image shows a dozen huge rocks floating right next to each other, it’s fake. If the lighting is coming from the side (instead of basically "front-lit" from the Sun far behind the camera), it’s likely an illustration.

- Track the "TNOs": Search for "Trans-Neptunian Objects" (TNOs) on academic databases. This is the scientific term for the Kuiper Belt family. You'll find way more rigorous data using that term than just searching for "Kuiper Belt."

The Kuiper Belt isn't just a ring of ice; it’s the frontier. It’s the limit of where our Sun’s influence starts to fade. Every new image of Kuiper Belt objects we capture is a tiny bit more light shed on the dark corners of our neighborhood. It’s slow work, and it’s often frustratingly blurry, but it’s the only way we’re ever going to understand the true scale of the place we call home.