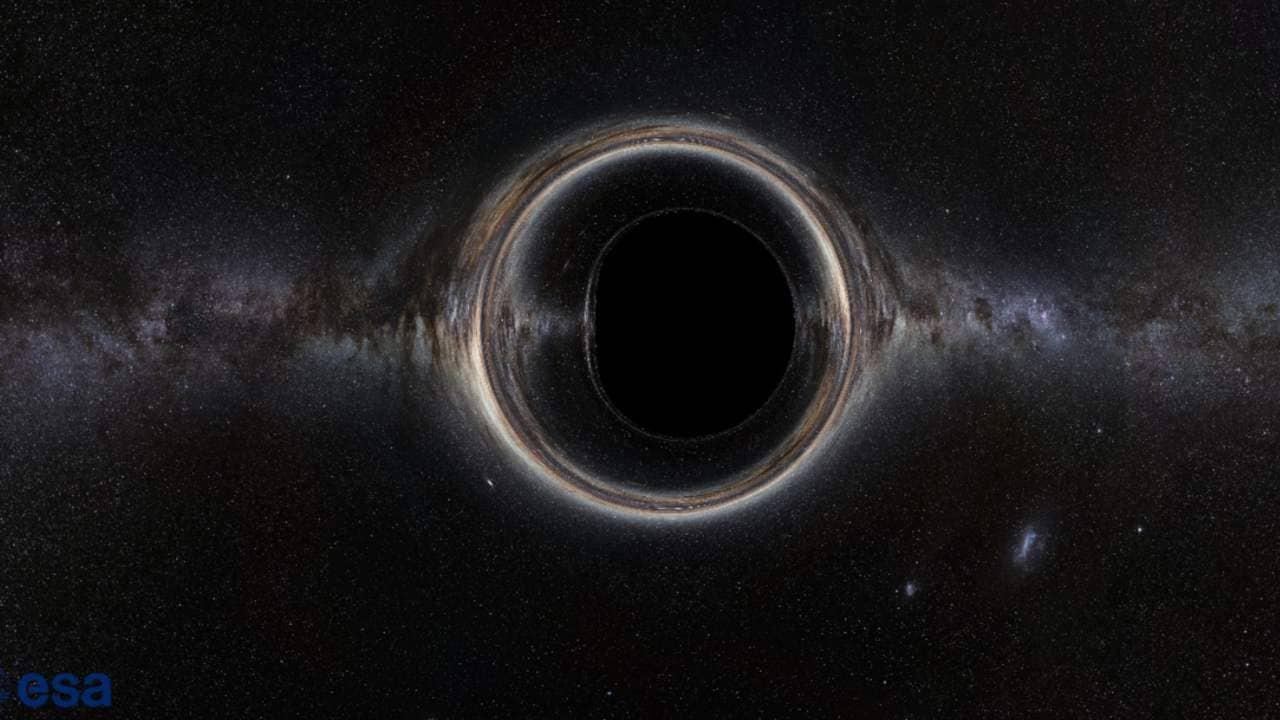

It looked like a fuzzy orange donut. Honestly, when the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) team dropped that image in April 2019, some people were a little underwhelmed. We’ve been spoiled by Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar and decades of high-budget CGI. But that blurry ring was a literal impossible feat. It was the first photograph of a black hole, specifically the supermassive beast at the center of the Messier 87 (M87) galaxy. We weren't just looking at a picture; we were looking at the edge of physics.

Space is big. Really big. To get that shot of M87*, which is 55 million light-years away, scientists needed a telescope the size of Earth. Since they couldn't build a physical dish that massive, they used a technique called Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI). They synced up eight different radio observatories across the globe—from the South Pole to the French Alps—to act as one giant lens.

How the Photograph of a Black Hole Actually Works

You aren't seeing the black hole itself. That’s physically impossible because, well, light can't escape it. What you’re seeing in the photograph of a black hole is the "shadow." The bright, glowing orange ring is the accretion disk. This is a swirling mess of superheated gas and dust spinning around the abyss at near-light speeds.

The dark center? That's the event horizon's shadow. Gravity is so intense there that it bends light around it like a cosmic lens. This is a phenomenon called gravitational lensing. Albert Einstein predicted this over a century ago with his General Theory of Relativity. Seeing it confirmed in a grainy, orange-hued photo was a "mic drop" moment for the scientific community. It turns out Einstein was right. Again.

Why Is It Always Orange?

People ask this a lot. Is the gas actually orange? Not really. The EHT captures radio waves, not visible light. Radio waves are invisible to the human eye. The researchers chose the orange color palette to represent the intensity of the brightness of the radio emissions. It’s a heat map, basically. If they had chosen blue or neon green, the data would be exactly the same, but it might not look quite as "fiery."

The Data Problem Was a Nightmare

Think about your phone’s storage. Now imagine having so much data that you can't even send it over the internet. That was the reality for the EHT team. Each observatory involved in the photograph of a black hole project generated roughly 350 terabytes of data per day.

🔗 Read more: Why the Gun to Head Stock Image is Becoming a Digital Relic

They had to store this on physical hard drives. Thousands of pounds of hard drives. They literally had to fly these drives to central processing centers in Germany and the United States. In fact, they had to wait months for the Antarctic winter to end just so they could fly the data out of the South Pole. It was a logistical Herculean task.

Katie Bouman, a computer scientist who became the face of the algorithm development, led the creation of a program called CHIRP. Since the "Earth-sized telescope" still had gaps—it wasn't a solid dish, after all—the algorithm had to fill in the missing pieces of the puzzle. It’s like trying to listen to a song when only 10% of the notes are being played, but you still recognize the tune.

Sagittarius A* vs. M87*

A few years after the M87* breakthrough, we got a second photograph of a black hole, this time of Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*). This is our black hole—the one in the center of the Milky Way.

Interestingly, Sgr A* was much harder to photograph than M87*, even though it’s way closer. Why? Because it’s smaller and changes much faster. M87* is a monster; it’s 6.5 billion times the mass of our sun. It takes days or weeks for the gas around it to complete an orbit. Sgr A* is a "runt" by comparison, only 4 million solar masses. The gas orbits it in minutes. Trying to take its picture is like trying to photograph a hyperactive puppy that won't sit still, whereas M87* is a giant, slow-moving elephant.

Dealing with the Skeptics

Whenever something this monumental happens, the skeptics come out. Some claimed the image was just a "CGI simulation" or that the algorithms forced the data to look like a ring because that’s what the scientists expected to see.

💡 You might also like: Who is Blue Origin and Why Should You Care About Bezos's Space Dream?

The EHT team anticipated this. They used four different teams working independently with different algorithms to reconstruct the image. They weren't allowed to talk to each other. When all four teams came back with the same donut shape, they knew they had the real deal. It wasn't a fluke.

What This Means for the Future of Physics

The photograph of a black hole isn't just a cool wallpaper for your laptop. It’s a laboratory. By studying the ring's shape and the way light bends, physicists can test the limits of gravity.

We are currently looking for "cracks" in Einstein’s theories. So far, General Relativity has passed every test, but many scientists think it’s incomplete because it doesn't play nice with quantum mechanics. If we can get higher-resolution images—perhaps by putting telescopes into orbit—we might finally see something that Einstein didn't predict. That’s where the real "new physics" will begin.

Moving Beyond the "Fuzzy" Image

The next step is "Black Hole Cam." We don't just want stills; we want movies. By adding more telescopes to the array, the EHT project hopes to capture the dynamics of these objects in real-time. We want to see the "flicker" of the gas as it falls into the point of no return.

Recently, researchers used AI—specifically a technique called PRIMO—to sharpen the original M87* image. The new version shows a much thinner, crisper ring. It’s still based on the same 2017 data, but with better "glasses" to see it through.

📖 Related: The Dogger Bank Wind Farm Is Huge—Here Is What You Actually Need To Know

Why You Should Care

It’s easy to feel small when looking at a photograph of a black hole. You should. These things are the ultimate vacuum cleaners of the universe. Anything that crosses the event horizon is gone forever. Information, light, matter—swallowed.

But it’s also a testament to human ingenuity. We are tiny primates on a wet rock, and we figured out how to see something invisible 55 million light-years away. That’s pretty incredible.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you want to stay updated on the next phase of black hole imaging, keep an eye on these specific areas:

- Follow the EHT (Event Horizon Telescope) official site: They release the raw data and processed images periodically. They are currently working on adding space-based telescopes to the array to increase resolution.

- Look into the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) findings: While JWST doesn't take "photographs" of event horizons like the EHT, it studies the surrounding galaxies and the jets of matter black holes spit out, providing the context the EHT lacks.

- Explore the "Black Hole" section on ArXiv.org: If you want the real, unvarnished science, search for "Event Horizon Telescope" on ArXiv. This is where the researchers post their pre-print papers. It’s heavy on the math, but the abstracts are usually readable for a layperson.

- Check out "Interstellar" again: Watch the movie and then compare the "Gargantua" black hole to the real M87* photo. Knowing that the movie's visuals were based on actual equations provided by Nobel laureate Kip Thorne makes the comparison fascinating.

The era of black hole astronomy is just starting. We’ve moved from "theories on a chalkboard" to "actual pictures on a screen" in a single generation. Don't stop looking up.