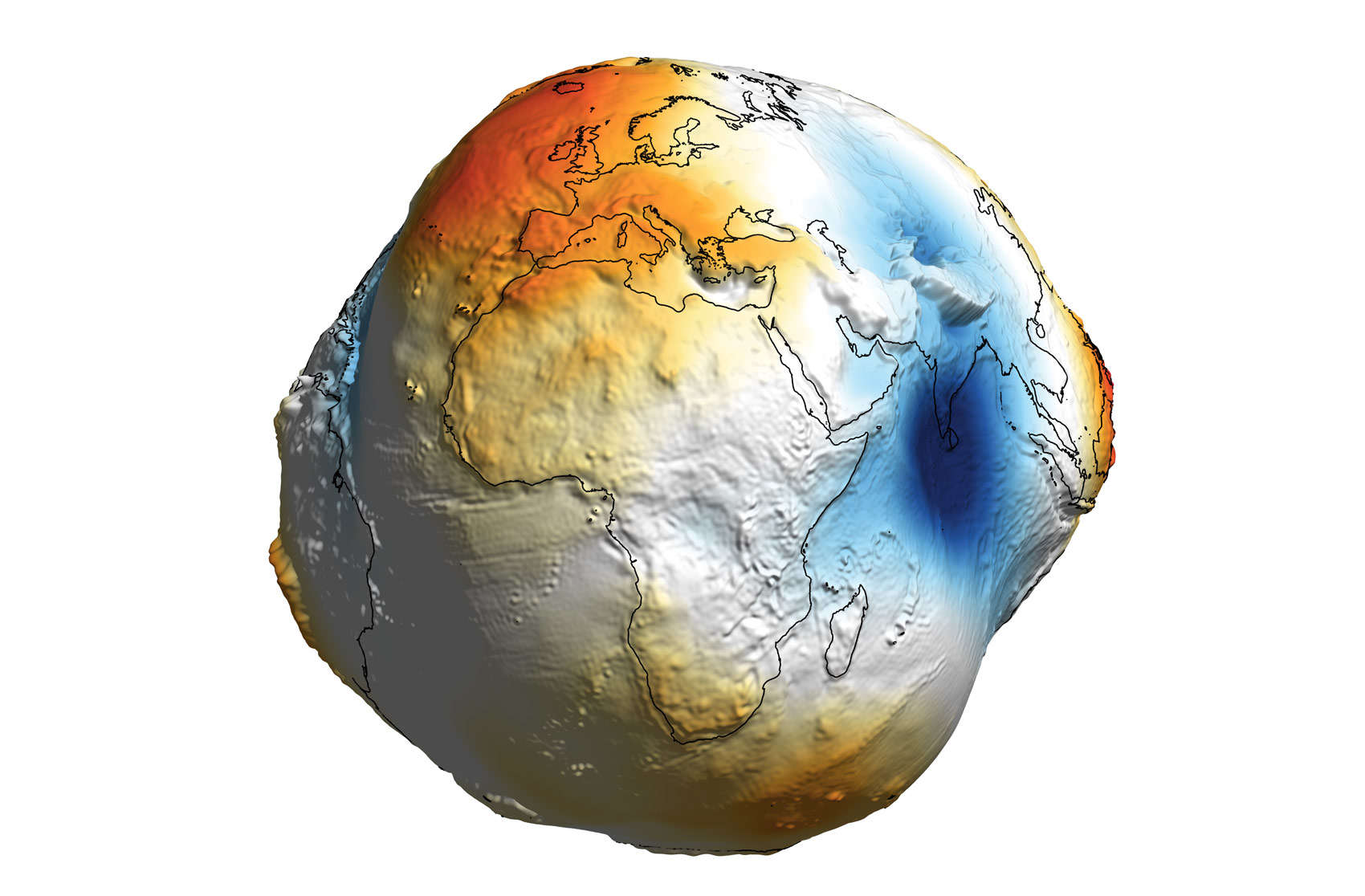

You've probably seen it. It pops up on your feed every few months, usually accompanied by some breathless caption about how "this is what Earth looks like without the oceans." It’s a weird, lumpy, multicolored blob that looks more like a rotting potato or a piece of chewed gum than a planet. People share it, get existential for a second, and move on.

The problem? It's not a photo. It’s not even a visualization of what a "dry" Earth would look like.

Honestly, the real earth image without water—if we were to actually suck the oceans dry—would look surprisingly boring. It would look like a slightly smaller, dustier version of the blue marble we already know. The "Potato Earth" is actually a visualization of gravity, not physical shape. We’re talking about the Geoid.

The Viral Lie and the Geoid Truth

The most famous earth image without water isn't a map of terrain. It’s a model created by the European Space Agency (ESA) using data from the GOCE satellite (Gravity Field and Steady-State Ocean Circulation Explorer).

Physics is weird. Gravity isn't uniform.

Because the Earth isn't a perfect sphere—it’s an oblate spheroid that bulges at the equator—and because the crust varies in density, gravity pulls harder in some places than others. If you have a massive mountain range or a particularly dense tectonic plate, gravity is a tiny bit stronger there. The "Lumpy Potato" image is an exaggerated map of these gravitational anomalies. If the ocean were influenced only by gravity, and not by tides or winds, it would settle into that lumpy shape.

But if you actually removed the water? The height difference between the deepest trench and the highest peak is about 19.3 kilometers. That sounds like a lot. In the context of a planet that is about 12,742 kilometers wide? It’s nothing.

On a billiard-ball scale, Earth is smoother than the ball you’d use at a pool hall. If you ran your hand over a dry Earth, you'd barely feel the Himalayas.

Why the exaggeration matters

We use these exaggerated models for science, not for aesthetics. The GOCE data helps researchers understand ocean circulation and sea-level change. By knowing what the "level" surface of the ocean should be based on gravity, scientists can measure how much it's actually deviating due to heat and currents.

It’s crucial for climate modeling. But it’s terrible for a realistic mental picture of our home.

What a Realistic Earth Image Without Water Actually Shows

If we actually drained the Atlantic, the Pacific, and the Indian Oceans tomorrow, the first thing you'd notice isn't the lumpiness. It’s the scars.

The ocean floor is rugged.

You’d see the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a massive underwater mountain range that’s actually the longest on the planet. It’s where the plates are pulling apart. You’d see the Mariana Trench, which would look like a terrifying, dark slit in the crust. But from space? You’d mostly see a lot of brown and grey.

The continental shelves would look like massive, flat plateaus surrounding the familiar shapes of the continents. Florida wouldn't be a peninsula anymore; it would be a high, flat highland overlooking a vast, dusty basin.

The Color Problem

Most "dry Earth" renders get the color wrong too. They show a bright, sandy desert everywhere. In reality, the ocean floor is covered in thick layers of sediment—basically marine "snow" consisting of dead plankton, volcanic ash, and dust that has settled over millions of years.

It wouldn't be a golden desert. It would likely be a muddy, dark, salt-encrusted wasteland. Think of a dry lake bed, but on a planetary scale.

James O'Donoghue, a planetary scientist formerly at NASA, actually created a high-quality animation showing this process. As the water level drops, the first things to appear are the continental shelves. Most of these are within 150 meters of the surface. By the time you hit 6,000 meters down, almost all the water is gone, except for the deep trenches.

It’s a stark, skeletal view of the world.

The Physics of a Dry Planet

Without the weight of the water, the Earth would actually change shape. This is a concept called "isostatic rebound."

The ocean is heavy. Really heavy.

There are about 1.332 billion cubic kilometers of water in the ocean. That weight presses down on the oceanic crust. If you removed it, the crust would literally spring back up. We see this happening today in places like Scandinavia and parts of Canada, where the land is still rising because the heavy ice sheets from the last Ice Age melted.

If we had a permanent earth image without water, the "potato" shape would actually start to flatten out as the crust adjusted to the lack of pressure.

Atmosphere and Life

We can’t talk about a dry Earth without acknowledging that it would be a dead Earth. The oceans are the planet's heat sink. They regulate the temperature. Without them, we’d have extreme swings like Mars or Venus.

🔗 Read more: Why You Can't Just Say Show Me a Picture of My Mom to Your Phone

The atmosphere would also change. Oceans absorb CO2. Without them, the greenhouse effect would likely spiral out of control. So, any "realistic" image would also have to account for a massive change in cloud cover—or the total lack thereof. You’d be looking at a hazy, dusty marble.

How to Spot a Fake "Dry Earth"

Next time you see an earth image without water going viral, check for these three red flags:

- Extreme Vertical Exaggeration: If it looks like a piece of popcorn, it's a gravity map (Geoid), not a shape map.

- Bright Blue Puddles: Many fakes keep some water in the trenches but make them look like pristine Caribbean lagoons. In reality, that leftover water would be hyper-saline sludge.

- Perfect Sphere: If the image shows a perfectly smooth, white ball, it’s ignoring the actual topography of the ocean floor.

NASA's "Visible Earth" project and the NOAA's bathymetry data are the gold standards here. They show the ridges, the valleys, and the plains in their true, muted colors.

Actionable Steps for Exploring Planetary Data

If you’re interested in what the world actually looks like beneath the waves, don't rely on social media memes. You can access the real data yourself.

- Use Google Earth Pro: You can actually turn off the "water surface" layer in the desktop version. It allows you to fly through the Monterey Canyon or over the Mid-Atlantic Ridge as if the water wasn't there. It uses real sonar data.

- Check the NOAA Bathymetry Viewer: This is the most accurate tool available to the public. You can see the actual depth soundings and the ruggedness of the seafloor without the "potato" exaggeration.

- Search for "GOCE Geoid" specifically: If you want to see the gravity map, search for it by its real name. It’s a fascinating piece of science, just don’t confuse it with the physical shape of the rocks.

- Verify the source: If an image doesn't credit a specific space agency (NASA, ESA, JAXA) or a university research department, it’s probably a CGI artist's interpretation rather than a scientific model.

Understanding the difference between a gravity model and a topographical model changes how you see the planet. We live on a world that is remarkably smooth, incredibly delicate, and currently very, very wet. Let's keep it that way.