Earth isn't alone. Not really. When we talk about planets that are terrestrial, we’re basically talking about the "Earth-like" crowd—the rocky, solid worlds where you could actually plant your feet without falling through a gas cloud. In our own neighborhood, we’ve got four of them: Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. But honestly, the more we look into deep space using tools like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the more we realize that "terrestrial" is a broad label for some pretty chaotic environments.

Space is mostly empty. Then you have these dense, heavy clumps of silicate rocks and metals that managed to survive the sun’s early temper tantrums. These aren't the gas giants like Jupiter that are basically just massive, swirling storms of hydrogen. Terrestrial worlds have layers. They have crusts. Most have molten cores.

What makes a planet terrestrial anyway?

It’s all about the "stuff." If you can stand on it, it’s a start. Astronomers define planets that are terrestrial by their compact, rocky surfaces. They usually have a central metallic core, mostly iron, with a silicate mantle wrapped around it. Think of it like a peach; the pit is the core, the flesh is the mantle, and the skin is the crust.

Mercury is the weird one here. It’s tiny. It’s basically a giant ball of metal with a thin rocky shell, probably because a massive collision billions of years ago stripped its outer layers away. It has almost no atmosphere. On the flip side, you have Venus. Venus is basically a terrestrial planet gone wrong. It has a runaway greenhouse effect that makes the surface hot enough to melt lead. It’s a rocky world, sure, but it’s a hellscape.

Size matters, but so does location. Most terrestrial planets stay close to their stars. In our solar system, they occupy the inner circle. This is because, in the early days of the solar system, it was too hot for volatile gases like helium and hydrogen to condense near the sun. Only the heavy stuff—metal and rock—could hang out there.

The "Big Four" in our backyard

We know Earth. It’s the gold standard. It has liquid water, a nitrogen-oxygen atmosphere, and active plate tectonics. But the other planets that are terrestrial in our system tell a story of what could have been.

- Mars: The Red Planet is half the size of Earth. It’s a desert. It used to have water—we see the dried-up riverbeds and minerals that only form in water, like hematite. But it lost its magnetic field, and the solar wind stripped its atmosphere away. Now it’s a frozen rock.

- Venus: Often called Earth’s "sister planet" because it’s nearly the same size and mass. But the similarity ends there. Its atmospheric pressure is 92 times that of Earth. If you stood there, you’d be crushed and fried simultaneously.

- Mercury: The smallest. It’s heavily cratered, looking a lot like our moon. It swings between 800°F during the day and -290°F at night.

NASA’s Perseverance rover is currently crawling across Jezero Crater on Mars, looking for signs of ancient life. Why? Because Mars is the most accessible terrestrial planet that might have once looked like home. We aren't looking for little green men; we’re looking for microscopic fossils in the silt.

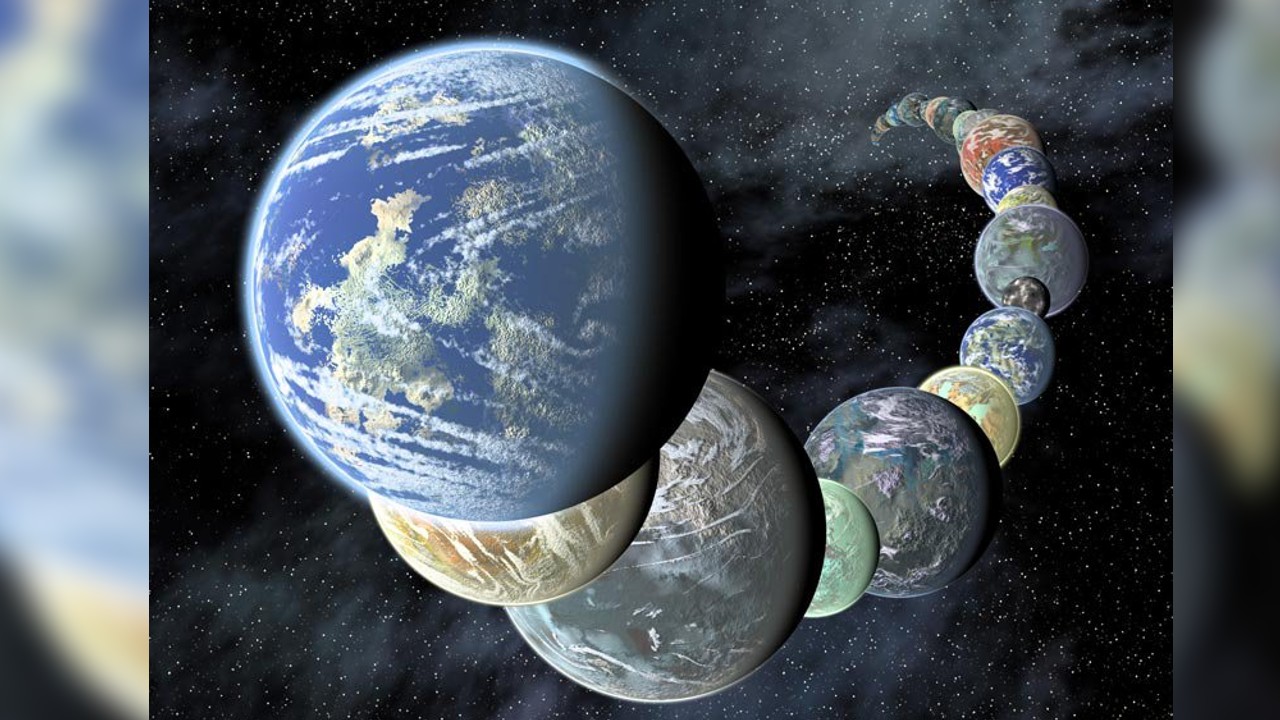

Beyond our Sun: The search for Exoplanets

This is where things get wild. We’ve found thousands of exoplanets, and a good chunk of them are terrestrial. Dr. Sara Seager, an astrophysicist at MIT, has spent years looking at how we might detect life on these distant rocks by analyzing their atmospheres.

📖 Related: Bowers and Wilkins Headphones: Why Most People Overpay (and When You Actually Should)

We use the "Transit Method." Basically, we watch a star and see if it dims slightly. If it does, something passed in front of it. By looking at how the light filters through that planet's atmosphere (if it has one), we can tell what it’s made of. Carbon dioxide? Water vapor? Methane?

The TRAPPIST-1 System

This is the jackpot. About 40 light-years away, there’s a small, cool star called TRAPPIST-1. It has seven planets that are terrestrial orbiting it. Seven! Three of them sit in the "Habitable Zone," which is the "Goldilocks" area where it’s not too hot and not too cold for liquid water to exist.

But there’s a catch. These planets are likely "tidally locked." This means one side always faces the star (permanent day) and one side always faces away (permanent night). Imagine a world where the sun never sets, but just hangs in the same spot in the sky forever. The weather patterns on a terrestrial planet like that would be insane.

Why do we care about rocky worlds?

Because gas giants are impossible for us to inhabit. You can’t build a base on Saturn. If we want to find "Earth 2.0," we have to look at planets that are terrestrial.

There's a concept called the "Habitability Index." It’s not just about having a rocky surface. You need a magnetic field to shield from radiation. You need plate tectonics to recycle carbon and keep the temperature stable over millions of years. Earth has all of this. Mars lost its shield. Venus lost its cooling system.

👉 See also: Why Are Phones Good in School: The Benefits Most People Ignore

It’s a delicate balance.

Researchers like those at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy are studying "Super-Earths." These are terrestrial planets that are significantly larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune. We don't have one in our solar system, which is actually kind of weird. Most star systems seem to have them. They might have massive oceans or thick, crushing atmospheres, making them "terrestrial" but totally alien.

The Problem with Atmosphere

A rocky surface is just the floor. The atmosphere is the ceiling.

Mercury has an "exosphere," which is so thin it’s basically a vacuum. Mars has a thin CO2 atmosphere. Venus has a thick CO2 shroud with clouds of sulfuric acid. Earth has the perfect mix. When we look at planets that are terrestrial outside our system, the biggest challenge is figuring out if they even kept their air.

Small stars, like M-Dwarfs, are prone to solar flares. These flares can blast the atmosphere off a terrestrial planet in a few million years. If a planet is "bald," it can't host life as we know it.

Recent Discoveries (2024-2025)

Data from the JWST has recently suggested that some of the TRAPPIST planets might actually lack thick atmospheres. This was a bit of a bummer for those hoping for an easy "Earth 2.0." However, it’s taught us that the proximity to the star is a double-edged sword. You need the heat, but the heat might kill the atmosphere.

Identifying a Terrestrial Planet

If you’re looking at data, here’s how you spot one:

- High Density: They are heavy for their size. Lots of iron and rock.

- Low Number of Moons: Unlike Jupiter (which has 90+), terrestrial planets usually have few or none. Earth has one. Mars has two tiny ones. Mercury and Venus have zero.

- No Ring Systems: You won't find a rocky planet with rings like Saturn. The gravity and proximity to the sun usually prevent it.

- Slower Rotation: Compared to gas giants, which spin incredibly fast, terrestrial planets take their time.

Misconceptions about "Earth-Like"

We see the headlines all the time: "Earth-like planet found!"

Usually, that just means it’s terrestrial and roughly the same size as Earth. It doesn’t mean it has trees, oxygen, or water. It could be a roasted rock. It could be a world covered in global oceans with no land at all (often called "Ocean Worlds," though they still have a terrestrial core).

We also assume terrestrial planets must be warm. Not true. There are likely "Rogue Planets"—terrestrial worlds kicked out of their solar systems that are wandering through the freezing void of interstellar space. They are still terrestrial, just very, very cold.

Practical Insights for the Future

The study of planets that are terrestrial isn't just about finding a new home. It’s about understanding our own. By studying the "failed" Earths like Venus and Mars, we learn how fragile our own climate and magnetic protection really are.

If you want to follow this field, keep an eye on these specific projects:

- The Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO): A future NASA mission specifically designed to find at least 25 habitable-zone planets.

- ELT (Extremely Large Telescope): Currently under construction in Chile. It will be able to see the "pale blue dots" of distant terrestrial planets more clearly than ever before.

- Mars Sample Return: The joint NASA-ESA mission to bring actual rocks from Mars back to Earth. This will be the first time we analyze the crust of another terrestrial planet in a lab.

Understanding the diversity of rocky worlds helps us narrow down where to look for life. We are moving from "Is it rocky?" to "Does it breathe?"

To stay updated, check the NASA Exoplanet Archive regularly. It’s a live database of every confirmed world outside our system. You can filter by "Terrestrial" or "Rocky" to see exactly how many Earth-sized neighbors we’ve actually found. The number is growing every single week.

Pay attention to "spectroscopy" reports. That’s the real science. When a paper says they found "biosignatures" on a terrestrial planet, that’s the day the world changes. Until then, we’re just mapping the rocks in the dark.