Weather is local. We say that all the time, but looking at a temperature map of the United States usually tells a story of broad strokes and giant blobs of color that don't quite explain why your neighbor's lawn is frosted while yours is just damp. It’s a mess of data. Thousands of sensors, satellite feeds, and complex algorithms try to paint a picture of what’s happening from the humid swamps of Florida to the bone-dry basins of Nevada.

Most people check these maps to see if they need a jacket. But if you're looking at the big picture, you're seeing a literal battlefield of air masses.

The Chaos Behind the Colors

When you open a digital temperature map of the United States, you aren't just looking at thermometer readings. You're looking at an interpolation. Because we don't have a sensor every ten feet, computers have to guess what’s happening in the "gray space" between weather stations. This is where things get tricky.

If you’ve ever noticed that the map says it's 75 degrees but your car thermometer insists it's 82, you’ve hit the "Urban Heat Island" effect. Concrete holds onto heat like a battery. National Weather Service (NWS) stations are often located at airports—wide open, grassy, wind-swept areas. They aren't sitting in the middle of a downtown parking lot. So, the temperature map of the United States that you see on a major news site might be technically accurate for the local airport, but it’s totally lying to you about your actual commute.

Why the Heat Map Looks Like a Patchwork Quilt

Temperature isn't a flat experience. It’s vertical.

The Western U.S. is the hardest part to map accurately. Think about the Sierra Nevada or the Rockies. You can have a 30-degree difference within five miles just because of elevation. Expert meteorologists, like those at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), use "High-Resolution Rapid Refresh" (HRRR) models to try and account for this. It’s a beast of a system. It updates every hour. It tries to simulate how wind moves over a mountain and carries heat with it.

Honestly, it’s a miracle it works at all.

Understanding the "Real Feel" vs. The Map

We’ve all seen those maps that turn a deep, angry purple during a heatwave. But those colors usually represent the dry bulb temperature—the actual air temp. They don't account for the "Heat Index" or "Wind Chill" unless you toggle a specific setting.

📖 Related: Casualties Vietnam War US: The Raw Numbers and the Stories They Don't Tell You

In the Southeast, 90 degrees feels like a steam room. In Arizona, it feels like a blow dryer. A standard temperature map of the United States often fails to convey the sheer physical toll of humidity. If you want to know how miserable you'll actually be, you need to look for the "Dew Point" layer. Meteorologists generally agree that once the dew point hits 70, you’re in "uncomfortable" territory. Once it hits 75, it’s oppressive.

The map doesn't always show that struggle. It just shows a number.

The Great Arctic Outbreaks

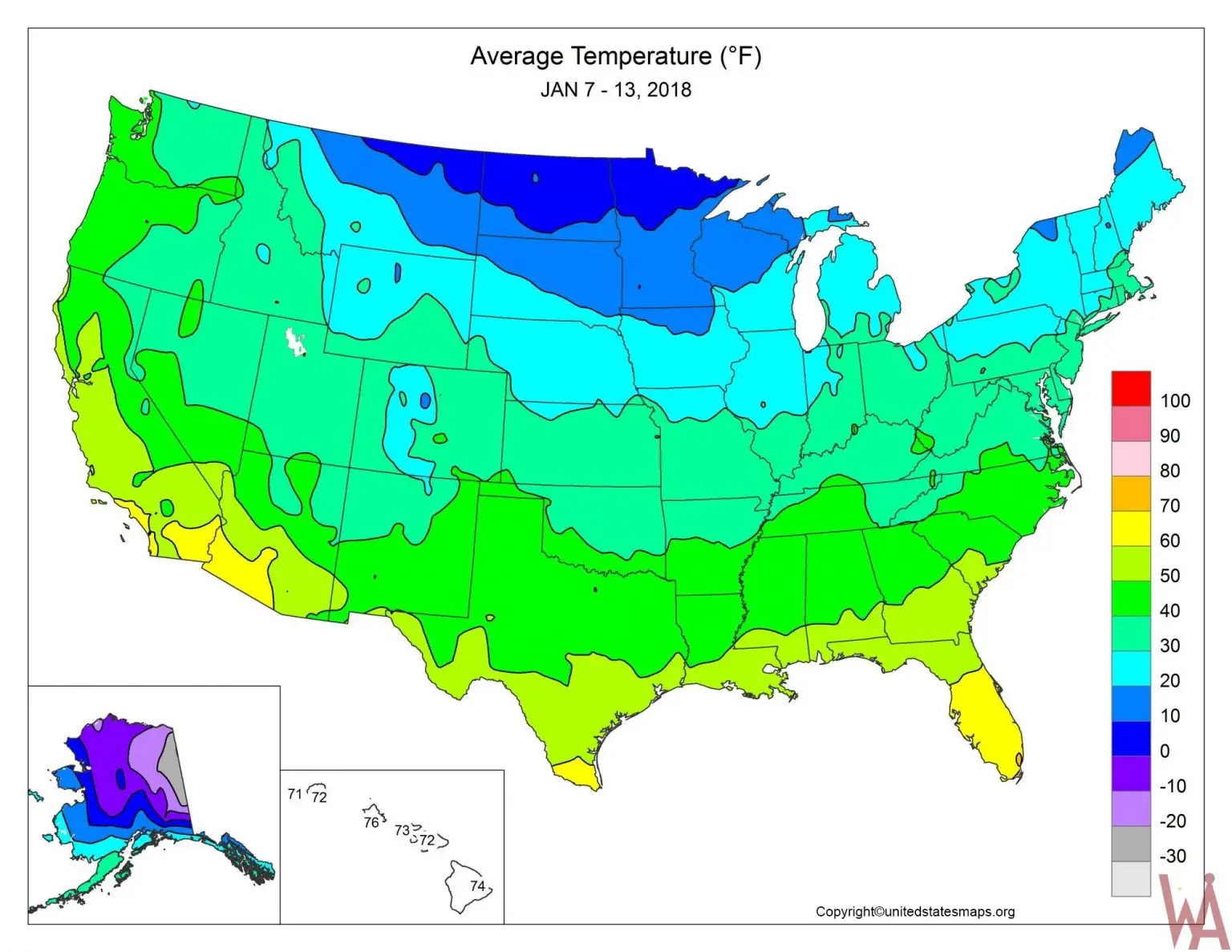

Every few winters, we hear about the "Polar Vortex." This is when the temperature map of the United States turns a terrifying shade of white and dark blue.

What’s actually happening is a disruption in the jet stream. Normally, the jet stream acts like a tight rubber band holding cold air up in the Arctic. When it weakens, it wobbles. It "loops" down into the lower 48. This creates those dramatic maps where Texas is colder than Alaska. It sounds like a freak occurrence, but it’s becoming a predictable rhythm of our changing climate.

The 2021 Texas power grid crisis was a primary example of how a map can be a warning sign that we ignore until the lights go out. The map showed the "blue" moving south days in advance.

How to Read a Temperature Map Like a Pro

If you want to actually use these maps for something other than casual conversation, you have to look at the gradients.

Look for where the colors bunch up close together. Those are "fronts."

👉 See also: Carlos De Castro Pretelt: The Army Vet Challenging Arlington's Status Quo

- Cold Fronts: Usually represented by a sharp transition from warm colors to cold. Expect wind, maybe a storm, and a sudden drop in pressure.

- Warm Fronts: These are lazier. They slide in, often bringing gray skies and a slow, sticky rise in temperature.

- Stationary Fronts: When two air masses have a standoff. These are the ones that cause flooding because the rain just sits there.

Don't just look at your city. Look 200 miles to your west. In the U.S., weather generally moves west to east. If there’s a massive blob of red over Kansas and you’re in Ohio, you’d better find your shorts. It’s coming for you.

The Tech Powering the Map

We aren't just sticking a finger in the wind anymore. We use the GOES-R series satellites. These things are incredible. They sit in geostationary orbit, 22,000 miles up, and scan the United States constantly. They don't just "see" the heat; they measure the infrared radiation coming off the Earth's surface.

Then there’s the Mesonet.

Many states, like Oklahoma and New York, have their own high-density networks of weather stations. These provide a much more granular temperature map of the United States than the federal government can offer on its own. If you’re a farmer or a construction manager, these state-level maps are the gold standard. They measure soil temperature, solar radiation, and 2-meter air temps with extreme precision.

The Limitations of the "National" View

When you look at a map covering the whole country, you lose the "Microclimates."

San Francisco is the classic example. You can have a temperature map showing the Bay Area at a nice, even 65 degrees. But go to the Sunset District and it’s 55 with fog. Go to Walnut Creek and it’s 85. The national map generalizes. It has to. Otherwise, the screen would be a vibrating mess of pixels that no one could read.

It's the same in the Appalachians. Valleys trap cold air at night—a process called "Cold Air Pooling." You might be at the top of a ridge where it's 40 degrees, while the valley floor below is 28 and frosty. A standard temperature map of the United States usually misses these nuances unless you zoom way, way in.

✨ Don't miss: Blanket Primary Explained: Why This Voting System Is So Controversial

The Role of Oceans

Water is the great stabilizer. The Pacific and Atlantic Oceans act like massive thermal batteries. This is why the West Coast temperature map often looks "boring." It’s just a narrow strip of green and yellow all year. The ocean doesn't want to change temperature quickly.

Meanwhile, the middle of the country is a wild west of thermal swings. Without a large body of water to regulate things, the Central U.S. can swing 50 degrees in 24 hours. If you live in Nebraska, you know the map can look completely different by lunchtime than it did at breakfast.

Practical Steps for Accurate Monitoring

Stop relying on the default weather app on your phone. Most of those use the GFS (Global Forecast System) model, which is okay, but it’s often "low res" compared to others.

If you want the real deal, use the NWS Digital Forecast Database. It's not as "pretty" as the commercial apps, but it's what the pros use.

Another tip: check the ASOS (Automated Surface Observing Systems) data if you live near a city. This is the raw, unedited data from airports. It’s the most "honest" temperature reading you’re going to get, even if it doesn't account for your specific backyard's shade.

Lastly, pay attention to the "Anomaly" maps. A temperature map of the United States that shows "Degrees Departure from Normal" is often more useful than the raw temperature. It tells you if what you’re experiencing is a freak event or just a standard Tuesday. If the map shows a 20-degree positive anomaly, your local power grid is going to be under massive stress from air conditioning demand.

The map is a tool, not a crystal ball. It’s a snapshot of a chaotic, fluid system that’s trying to find balance. The next time you see a giant wave of red or blue sweeping across the screen, remember that it's just trillions of air molecules trying to get from one place to another.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Switch to a High-Resolution Source: Download an app that uses the HRRR model for short-term (1-18 hour) temperature maps. It's significantly more accurate for timing fronts than the standard GFS model used by most "free" apps.

- Locate Your Nearest Mesonet: Search for your state’s name plus "Mesonet" (e.g., "NY Mesonet"). These sites offer granular, ground-level data that national maps often overlook.

- Check the Dew Point, Not Just Temp: If you're planning outdoor work or exercise, look at the dew point map. Anything above 65°F will drastically change how your body handles the heat, regardless of what the "actual" temperature says.

- Calibrate Your Expectations: Recognize that the "city" temperature on a national map is likely taken at a windswept airport. If you are in a dense urban center, add 3-5 degrees to whatever the map shows during a summer afternoon.