You’ve probably heard it in a drafty country church or maybe a polished cathedral with acoustics that make your skin tingle. It’s a staple. Honestly, if you grew up anywhere near a hymnal, Tell Me the Story of Jesus is likely burned into your brain. But here’s the thing: most people just mouth the words without realizing the absolute powerhouse of a woman who wrote them or the weirdly specific history behind its "earworm" melody.

It isn’t just a Sunday morning filler.

Fanny Crosby wrote this in 1880. If you don't know Fanny, she was basically the Bob Dylan of 19th-century hymnody, except she was blind, lived in Manhattan tenements by choice, and wrote about 8,000 poems. That’s not a typo. Eight thousand. She was a powerhouse.

The Woman Behind Tell Me the Story of Jesus

Fanny Crosby didn't have an easy life, but she’d be the first to tell you she didn't want your pity. Blinded shortly after birth due to a medical mishap—a doctor applied mustard poultices to her eyes—she spent her life seeing things in a way most of us can't quite grasp. When she sat down to write Tell Me the Story of Jesus, she wasn't just checking a box. She was writing from a place of deep, personal obsession with the narrative of the Gospels.

She had this uncanny ability to take complex theology and boil it down to something a kid could understand while a scholar could still find it moving. It’s a gift. Seriously.

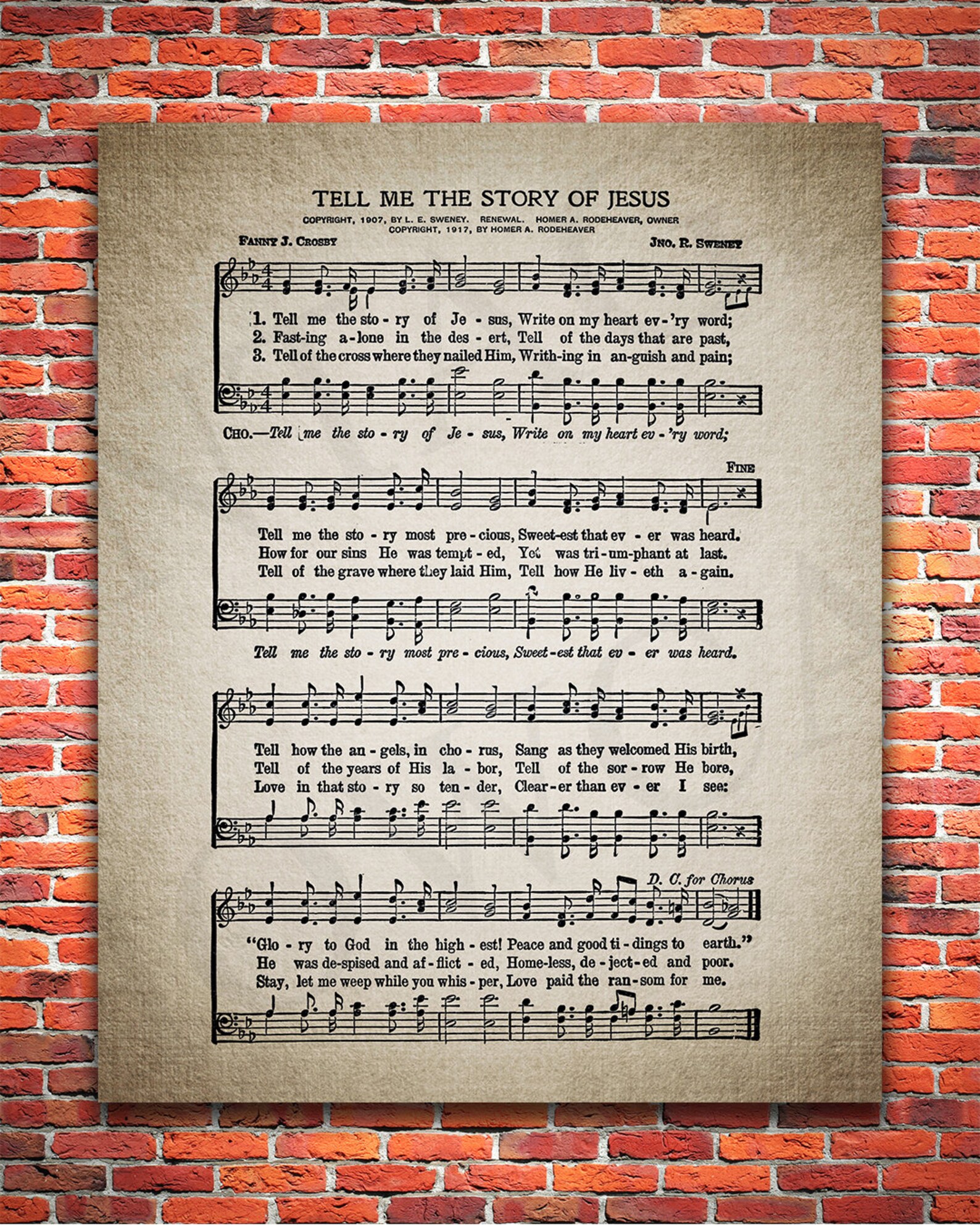

John R. Sweney composed the music. Sweney was a giant in the "Gospel Song" movement, which was basically the pop music of the late 1800s. People think of hymns as these dusty, ancient relics, but back then? These were hits. They were the songs people hummed while hanging laundry or walking to work. Sweney’s tune for this specific hymn is repetitive on purpose. It’s designed to be a "memory palace" for the story of Christ.

Why the lyrics feel different

Look at the first line. "Tell me the story of Jesus, write on my heart every word." It’s an invitation. It’s not a lecture.

🔗 Read more: At Home French Manicure: Why Yours Looks Cheap and How to Fix It

Most hymns of that era were busy being very "thou art" and "grandeur of God," but Fanny kept it grounded. She hits the highlights: the angels singing to shepherds, the fasting in the desert, the pain of the crucifixion, and the victory of the resurrection. It’s essentially a three-minute biography set to a Victorian waltz-time signature.

She uses words like "precious" and "sweetest," which might feel a bit sugary to a modern ear, but in 1880, that was the language of intimacy. She was trying to bridge the gap between a distant, terrifying God and a personal friend.

The Architecture of a 19th-Century Hit

The structure of Tell Me the Story of Jesus follows a very specific pattern that made it stick in the public consciousness. You have the verse, which sets the scene, and then that soaring refrain.

"Tell me the story of Jesus, write on my heart every word; tell me the story most precious, sweetest that ever was heard."

Musically, Sweney uses a lot of "step-wise" motion. This means the notes aren't jumping all over the place. It’s easy to sing. Even if you’re tone-deaf, you can probably manage this one. That was the point of the Sunday School movement. They wanted songs that could be taught to uneducated workers and children in about five minutes.

It worked.

💡 You might also like: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

The song first appeared in a collection called The Banner of Victory in 1880. Within a decade, it was in almost every major Protestant hymnal in America and the UK. It crossed denominational lines faster than almost any other song of its time. Baptists loved it. Methodists loved it. Presbyterians sang it (maybe a little slower).

The "Lost" Verses and Variations

Most modern hymnals only keep three or four verses. But Crosby often wrote more. In the original versions, there's more emphasis on the "Man of Sorrows" aspect.

There’s a specific verse about the "wilderness thicket" and the "temptation" that often gets cut today because it’s a bit darker. We like the "angels singing" part, but we’re less comfortable with the "fasting and hungry" part. Fanny didn't shy away from that. She knew that for a story to be "precious," it had to involve some level of struggle.

Why We Still Sing It (Even the Secular Crowd)

You might wonder why a song from the 1880s still shows up in movies, folk albums, and modern worship sets. It’s the nostalgia factor, sure. But it’s also the rhythm.

There is a cadence to Tell Me the Story of Jesus that mimics a heartbeat.

Cultural historians like Dr. Edith Blumhofer, who wrote extensively on Crosby, point out that these hymns became the "folk music" of the American immigrant experience. People coming from Europe, moving into crowded cities, found comfort in these simple, repetitive truths. It offered a sense of continuity in a world that was changing way too fast—sound familiar?

📖 Related: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

The 1880s were a time of massive technological upheaval. The lightbulb was new. The telephone was a weird toy. In the middle of that chaos, a song asking for a "story" provided a psychological anchor.

Common Misconceptions

- Myth 1: It’s a Christmas hymn. Nope. While it mentions the angels and shepherds, it covers the entire life and death of Jesus. It's an all-seasons track.

- Myth 2: Fanny Crosby wrote the music. She almost never did. She was a lyricist (or "lyrist," as they said then). She worked with guys like Sweney, William Doane, and Robert Lowry.

- Myth 3: It’s "traditional" in the sense of being centuries old. It’s actually relatively modern compared to stuff like "A Mighty Fortress Is Our God" (1520s). It’s "Gospel," not "Chorale."

How to Actually Use This Information

If you’re a worship leader, a music history buff, or just someone who likes old songs, there’s a way to appreciate this hymn without it feeling like a museum piece.

First, try slowing it down. Most congregations rush through it like they’re trying to catch a bus. If you pull back the tempo, the lyrics about "fasting and hunger" actually have room to breathe.

Second, look at the "story" aspect. We live in a world of snippets and 15-second clips. The hymn asks for the whole story. There’s a psychological benefit to narrative—to seeing things from beginning to end.

Practical Next Steps for the Curious

- Listen to different versions: Check out the version by The Isaacs for a bluegrass feel, or look for 1920s-era recordings on the Smithsonsian Folkways site to hear how it sounded before it got "sanitized" by modern production.

- Read Fanny Crosby’s autobiography: It’s called Memories of Eighty Years. It is wild. She talks about meeting presidents and her friendship with Grover Cleveland.

- Compare the lyrics: Open a 19th-century hymnal (you can find them on Google Books or Archive.org) and see what verses your modern church left out. You’ll usually find the "missing" verses are the most poetically interesting.

- Study the "Gospel Song" Era: If you like this hymn, look up the works of Philip Bliss or Ira Sankey. It’s a rabbit hole of Victorian pop culture that explains a lot about why American church music sounds the way it does today.

The reality is that Tell Me the Story of Jesus survives because it taps into a basic human need: the desire to be told a story that matters. Whether you believe the theology or not, the craft behind the song is undeniable. It’s a masterclass in simplicity.

In a world that won’t shut up, a song that asks someone to "tell me a story" is actually pretty radical.