You’re probably eating something right now, or at least thinking about it. Maybe it’s a turkey sandwich, a crisp apple, or a bowl of pasta. Whatever it is, your mouth is doing a frantic, highly coordinated dance to make sure that food doesn't choke you. Humans are weird. We aren't specialized like a lion that only wants a zebra steak, and we aren't like a cow that spends eighteen hours a day grinding grass into a green paste. We are the ultimate generalists. The teeth of an omnivore are basically a toolkit designed by evolution for someone who can't make up their mind about lunch.

It’s about versatility.

If you look at a grizzly bear or a common raccoon, you’ll see the same structural "indecisiveness" that you find in your own mirror. We have tools for stabbing. We have tools for snipping. We have tools for grinding things into oblivion. It’s this specific dental architecture that allowed our ancestors to survive ice ages and migrations across the globe. When the fruit ran out, they ate meat. When the meat was scarce, they dug up tubers.

The Four-Part Harmony of Your Mouth

Your mouth isn't just a row of white blocks. It’s a tiered system. First, you’ve got the incisors. These are the four front teeth on the top and bottom. Think of them as the scissors. They are sharp, thin, and meant for "incising"—cutting into a piece of pizza or a carrot. If you were a pure carnivore, these would be smaller and less prominent. If you were a pure rodent, they’d be massive and never stop growing. For us, they are just the entry point.

Then come the canines. People love to point at these and claim they prove we are basically wolves, but honestly? Our canines are pretty pathetic compared to a silverback gorilla (who mostly eats plants, by the way) or a tiger. In the teeth of an omnivore, the canine is a transitional tool. It’s there to grip and tear. If you're eating a piece of tough jerky, your canines do the heavy lifting of anchoring that food so you can rip a piece off. They are the "vampire" teeth, sure, but in humans, they’ve been blunted down significantly over millions of years of evolution.

The Grinding Station

The real magic happens in the back. The premolars and molars are the workhorses of the omnivorous diet.

- Premolars (Bicuspids): These are like a hybrid between a canine and a molar. They have two points (cusps) and are great for crushing and tearing simultaneously.

- Molars: These are the flat-topped giants. Their job is simple: pulverize. Whether it's tough vegetable fibers or a piece of steak, the molars use a side-to-side grinding motion to break down cell walls and proteins.

This side-to-side movement is a huge giveaway. Pure carnivores, like cats, mostly move their jaws up and down. They "slice" their food. If you watch a dog eat, they aren't really chewing their kibble into a fine powder; they are cracking it and swallowing. As an omnivore, you have the specialized jaw joint—the temporomandibular joint (TMJ)—that allows for the lateral movement necessary to grind grains and fibrous plants.

📖 Related: Why PMS Food Cravings Are So Intense and What You Can Actually Do About Them

Why Omnivore Teeth Are Actually a Huge Risk

There's a trade-off for being able to eat everything. Since we have deep grooves in our molars (to help grind plants), we are incredibly susceptible to tooth decay.

Think about it. A cat has relatively smooth, blade-like teeth. Food doesn't really "stick" to them the same way. But because our teeth of an omnivore have complex "fissures" and "pits" on the chewing surfaces, we trap sugars and starches. Dr. Peter Ungar, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Arkansas, has spent decades looking at "microwear" on ancient teeth. He’s found that as soon as humans shifted toward more carbohydrate-heavy diets, our dental health took a massive hit. We have the gear to eat the sugar, but our teeth aren't naturally "self-cleaning" like the sharp teeth of a shark or a lion.

Bacteria like Streptococcus mutans love those flat molars. They set up shop in the valleys of your teeth and produce acid that eats through your enamel. It’s the price we pay for being able to enjoy both a steak and a sourdough loaf.

Comparing Humans to Other Omnivores

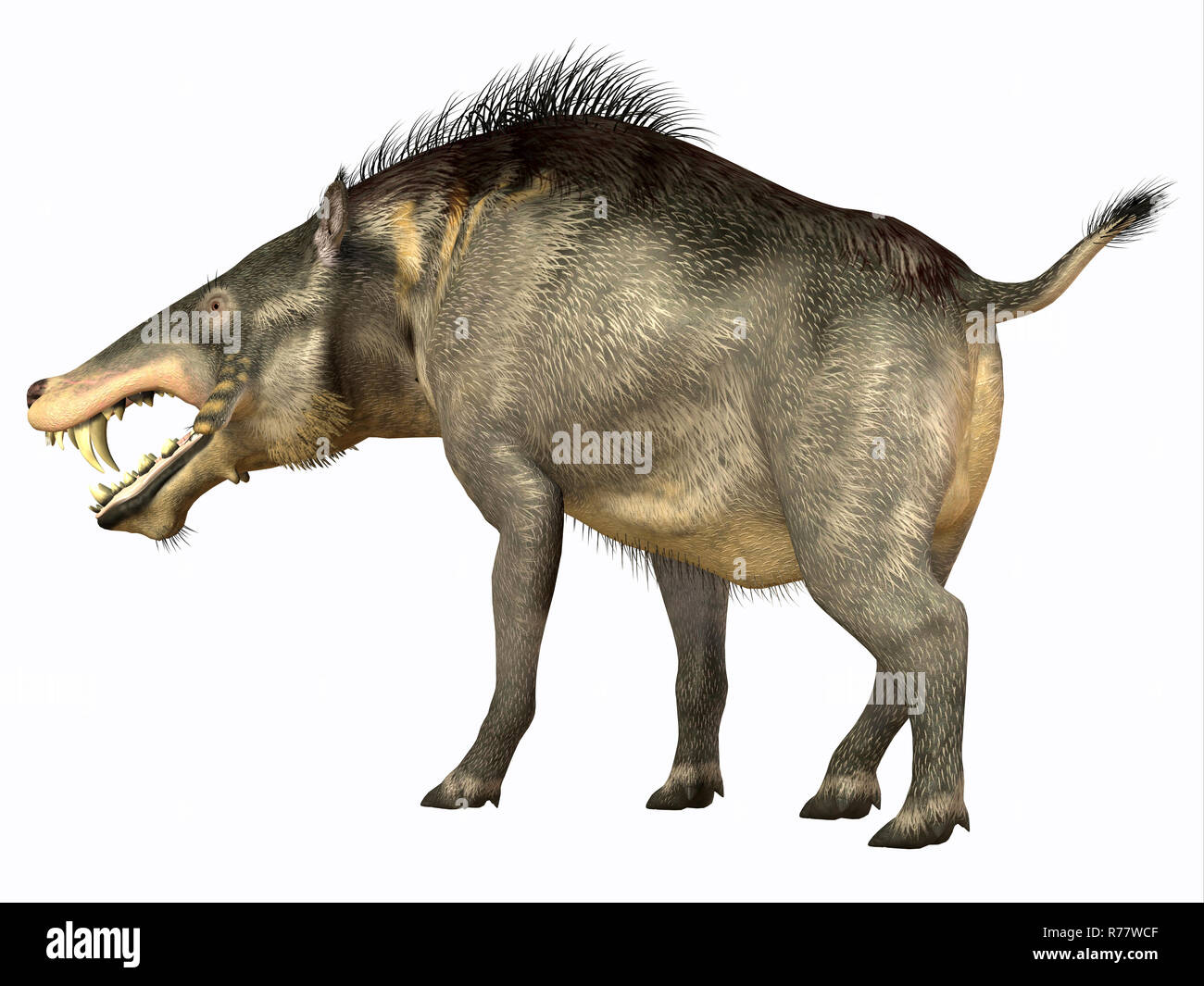

It’s helpful to look at our cousins in the animal kingdom to see how we stack up.

The Brown Bear: A bear's teeth are fascinating because they look like a "cranked up" version of ours. They have massive canines for catching fish or defending territory, but their molars are surprisingly flat. Why? Because a huge chunk of a bear's diet is berries, roots, and grasses. They need that grinding surface.

The Pig: Pigs are perhaps the most famous omnivores besides us. Their dentition is remarkably similar in function. They have incisors for rooting and clipping, but their molars are "bunodont," meaning they have rounded cusps. This is the gold standard for an all-purpose diet. It’s efficient for crushing acorns but can still handle animal protein if the opportunity arises.

👉 See also: 100 percent power of will: Why Most People Fail to Find It

The Chimpanzee: Our closest relatives have larger canines than we do, mostly for social display and fighting, but their overall tooth structure is built for fruit, insects, and the occasional small mammal. Our teeth are basically "refined" versions of chimp teeth—smaller, with thicker enamel, likely because we started cooking our food.

Cooking changed everything.

Once we started using fire, we didn't need massive jaw muscles or giant teeth to break down raw, tough collagen or woody fibers. Our teeth started getting smaller because the "pre-digestion" happening in the cooking pot did the hard work for us. This is why human mouths are often "too small" for our wisdom teeth now. We evolved smaller jaws faster than we lost the genetic blueprint for that third set of molars.

The Enamel Secret

The thickness of your enamel is a dead giveaway of your status as an omnivore.

Herbivores often have relatively thin enamel but teeth that grow continuously (like horses or rabbits) because they are constantly being worn down by silica in grass. Carnivores have very hard, dense enamel to prevent breakage when chomping on bone. Humans and other omnivores sit in the middle. We have thick enamel compared to many primates, which suggests our ancestors were eating "hard" foods like nuts, seeds, and underground storage organs (tubers).

If you look at the teeth of an omnivore under a microscope, you see a history of "pitting" and "scratching." Pits usually come from hard things like nuts. Scratches come from "shearing" things like leaves or meat. Human teeth show a chaotic mix of both. We are messy eaters.

✨ Don't miss: Children’s Hospital London Ontario: What Every Parent Actually Needs to Know

Misconceptions About the Omnivore Diet

A common myth is that humans are "naturally" herbivores because our intestines are long. While it's true our digestive tract is longer than a tiger's, our teeth tell a different story. If we were meant to be pure herbivores, our canines would likely be non-existent or modified into "tusks," and our incisors would be much broader for stripping bark or leaves.

Another weird myth: that we "need" to eat meat because we have canines.

That’s not quite right either. We have the capacity to eat meat. Evolution doesn't care about "need" as much as "opportunity." Our teeth provide us the opportunity to utilize calorie-dense animal fats when plants aren't available. We are opportunistic survivors. If you look at the Dentition Index, which measures the complexity of tooth shapes, omnivores consistently rank as having the most "geometrically diverse" mouths.

Maintaining Your Multi-Tool

Since you're rocking a set of teeth of an omnivore, you have to manage a mouth that is under constant biological siege. You have the bacteria that eat sugar and the physical wear and tear from grinding tough fibers.

Modern diets are actually "too soft" for our teeth.

Anthropologists have noted that ancient skulls often have perfectly straight teeth with no crowded wisdom teeth. Why? Because they chewed on tough, raw foods that stimulated jaw bone growth. Today, we eat mush. Soft bread, soft meat, cooked veggies. Our jaws don't grow to their full potential, leading to the orthodontic industry we see today.

Actionable Steps for Your Omnivorous Mouth

- Stimulate the Bone: Don't be afraid of "hard" foods. Carrots, apples, and nuts aren't just good for nutrients; the mechanical force of chewing helps maintain the density of the alveolar bone that holds your teeth in place.

- Mind the Fissures: Because your molars have those deep "omnivore pits," you can't just rinse your mouth and call it a day. You have to physically disrupt the biofilm in those grooves. This is why flossing is non-negotiable—your teeth are shaped to trap debris between them.

- Acid Neutralization: If you’ve been using your incisors to eat acidic fruits (like oranges), don't brush immediately. Omnivore enamel is tough, but it softens temporarily when exposed to acid. Wait 30 minutes for your saliva to re-mineralize the surface.

- Check for Grinding: Because we have the "side-to-side" jaw movement capability, many humans develop bruxism (teeth grinding) under stress. This flattens the cusps of your molars, effectively turning your "omnivore" teeth into inefficient "flat" plates. If your teeth look level or "straight across" on the bottom, talk to a dentist about a guard.

Your mouth is a biological masterpiece of compromise. It isn't perfect at any one thing, but it’s "good enough" at everything. That versatility is exactly why humans are currently the most dominant mammal on the planet. We can eat the forest, the field, and the sea, all thanks to a few specialized shapes of calcium and phosphorus. Keep those grinders clean; you're going to need them for your next meal.

Next Steps:

- Audit your chewing habits: Are you favoring one side? This can lead to uneven wear on your molars.

- Introduce more fibrous "primitive" foods into your diet to encourage jaw strength and natural tooth cleaning.

- Look at your teeth in the mirror and identify the four different types—incisors, canines, premolars, and molars—to see how your own "toolkit" is holding up.