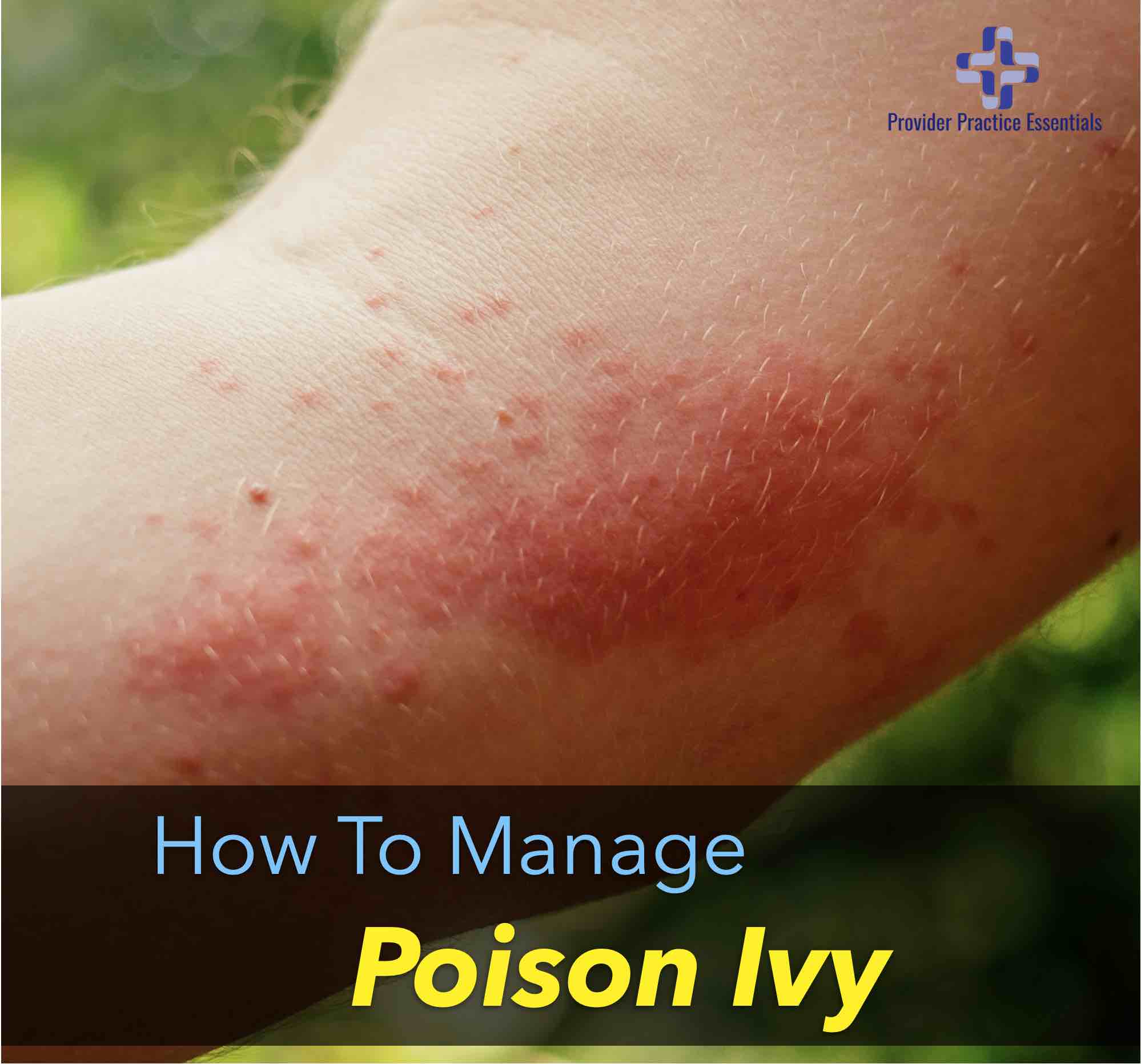

You’re hiking. The sun feels great, the trail is clear, and then you see it. Three leaves. Shiny. Maybe a little reddish. You think you brushed against it, but you aren't sure. Fast forward six hours and your ankle is bubbling into a blistered, weeping mess that feels like it’s being poked with hot needles. Naturally, you reach for the essential oils. Specifically, tea tree oil. It’s the "Swiss Army Knife" of natural medicine, right? But using tea tree oil for poison ivy isn't as straightforward as just dabbing it on and hoping for the best. Sometimes, it makes things way worse.

Urushiol is the oily resin found in poison ivy, oak, and sumac. It is incredibly sticky. It’s basically the glitter of the plant world; once it touches your skin, it hitches a ride on your cell membranes. Your immune system sees this oil and absolutely loses its mind. It triggers a T-cell mediated immune response. This isn't just a surface irritation; it’s a full-blown internal protest.

Why tea tree oil for poison ivy is a double-edged sword

Tea tree oil, or Melaleuca alternifolia, is famous for being antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory. It contains a compound called terpinen-4-ol. Studies, including a notable one published in the Archives of Dermatological Research, have shown that tea tree oil can reduce skin swelling in histamine-induced inflammation. That sounds perfect for a rash.

But here is the catch.

Poison ivy causes allergic contact dermatitis. Tea tree oil is also a common cause of... you guessed it, allergic contact dermatitis. If you have sensitive skin, or if you’ve developed a secondary sensitivity to oxidized tea tree oil, you are essentially pouring gasoline on a fire. You might think the poison ivy is spreading, but honestly, you might just be having a secondary reaction to the "cure."

The oxidation problem nobody mentions

Essential oils aren't immortal. When tea tree oil sits in a clear bottle on a sunny bathroom shelf, it oxidizes. The monoterpenes inside break down. This creates new compounds like ascaridole, which are much more likely to sensitize the skin. If you use old tea tree oil on an open poison ivy blister, you’re asking for trouble.

Always check your bottle. If it smells "off" or extra turpentine-like, toss it. It's not worth the risk when your skin is already compromised.

How to actually use it (if you must)

If you’ve used tea tree oil before without issues, it can help dry out the weeping blisters. Poison ivy rashes go through a "wet" phase. This is when the blisters pop and ooze. While the fluid inside the blisters doesn't actually spread the rash (that’s a total myth), it can lead to a secondary staph infection if you're scratching with dirty fingernails.

📖 Related: Upper Belly Fat Pictures: What Your Shape Actually Says About Your Health

Tea tree oil is a powerhouse against bacteria. It kills Staphylococcus aureus. By applying a diluted version, you’re basically keeping the site "clean" while it heals.

- Never apply it neat. "Neat" means undiluted. That’s a recipe for a chemical burn on top of an itchy rash.

- The 2% rule. Mix about 10-12 drops of tea tree oil into an ounce of carrier oil.

- Witch Hazel is your friend. Instead of an oily carrier, try mixing tea tree oil with witch hazel. It’s an astringent. It helps shrink the tissue and provides a cooling sensation that competes with the itch signals going to your brain.

The "Initial Wash" window

Timing is everything. You have about a 15 to 30-minute window after exposure to get the urushiol off your skin before it bonds. Once it bonds, you can't "wash it off." You're just washing the surface.

Some people swear by using tea tree oil soap immediately after a hike. Is it better than Dawn dish soap? Probably not. Urushiol is an oil. You need a surfactant—something that breaks down grease. Dish soap is designed to strip grease off a pan; it does the same for your arm. If you have tea tree soap, use it, but the friction and the degreasing agent are doing the heavy lifting, not the essential oil itself.

Real talk: When tea tree oil isn't enough

I've seen people try to "natural" their way through a systemic reaction. If the rash is on your face, your eyes are swelling shut, or it's covering more than 25% of your body, put the tea tree oil away. You need a professional. Prednisone is often the only thing that will shut down a severe urushiol reaction.

There's a specific type of misery that comes from a "rebound" rash. This happens when you take a short course of steroids, the rash starts to fade, and then it comes back twice as hard because the dose wasn't tapered correctly. A home remedy like tea tree oil won't help here. It’s an internal immune overreaction at that point.

Comparing tea tree to other natural remedies

People often lump tea tree oil in with things like jewelweed or bentonite clay. They work differently.

- Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis): Often grows right next to poison ivy. It contains lawsone, which has anti-inflammatory properties. It’s much gentler than tea tree.

- Bentonite Clay: This is a "pulling" agent. It dries into a mask and physically sucks the moisture out of the blisters. Tea tree oil can be added to a clay mask to provide that antimicrobial boost.

- Colloidal Oatmeal: This is for the "insane itch" phase. It coats the skin and protects the nerve endings. Tea tree is too aggressive for a soak; stick to the oatmeal for the bath and use tea tree for spot treatments.

Evidence-based safety

The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) generally recommends cool compresses, calamine lotion, and hydrocortisone. They are pretty quiet on essential oils. Why? Because the "expert" consensus is that the risk of a secondary skin reaction often outweighs the benefit of the antimicrobial properties.

However, if you are looking at tea tree oil for poison ivy as a way to prevent infection, there is logic there. A study in the Journal of Applied Microbiology confirmed that even at low concentrations, tea tree oil can disrupt the permeability of bacterial cell membranes. If you're a "scratcher," this is your insurance policy against a skin infection.

Steps to take right now

If you think you've been exposed or you're starting to itch, don't panic.

- Degrease immediately. Use a washcloth and lots of soap. The friction of the cloth is vital to physically lift the sticky urushiol.

- Cold, cold, cold. Heat dilates blood vessels and makes the itch feel more intense. Use cold water.

- Patch test. Before putting tea tree oil on your massive rash, put a tiny drop (diluted!) on a clear patch of skin. Wait 20 minutes. If it turns red, your body is saying "no thanks."

- Topical application. If the patch test is fine, mix 3 drops of tea tree oil with a tablespoon of aloe vera gel. The aloe cools, the tea tree protects. Apply it gently. Don't rub. Rubbing triggers more histamine release.

- Keep it breathable. Don't wrap the rash in plastic or heavy bandages. Oxygen helps the drying process. A light gauze wrap is fine if it’s oozing.

The reality is that poison ivy is a waiting game. Your body has to process the "invader." Tea tree oil is a tool in the kit, but it isn't a magic eraser. Use it for its strengths—cleaning and drying—but respect its potency. If the rash starts looking purple, you get a fever, or the streaks start moving up your arm, go to urgent care. No amount of Melaleuca can fix a systemic infection or a Grade-A allergic emergency.