It’s a scene you’ve probably seen in cartoons or history books. A mob of angry men in tri-cornered hats dumps a bucket of black goo over a terrified tax collector, shakes out a pillowcase of feathers, and marches him through town. It looks ridiculous. Almost funny. But if you were actually there in Boston or Charleston in the 1770s, you wouldn’t be laughing. It was horrific.

Tarring and feathering in the American Revolution wasn't just some wacky colonial prank; it was a calculated, brutal form of domestic terrorism designed to humiliate and physically destroy anyone who stayed loyal to the British Crown.

We talk a lot about "taxation without representation" and the high-minded ideals of the Founding Fathers. But the street-level reality of the Revolution was often messy, violent, and frankly, kind of gross. It wasn't just the British being "tyrants." The Patriots could be terrifyingly cruel to their own neighbors.

The Brutal Reality of the Pine Tar

Most people assume the "tar" used was the stuff we use on roads today. It wasn't. They mostly used pine tar, which was plentiful in the colonies for waterproofing ships.

To make it liquid enough to pour, you had to heat it up.

Think about that for a second. If the tar was too cool, it wouldn't stick. If it was too hot—and it often was—it caused second and third-degree burns. Imagine boiling sap being poured over your bare skin. It seeped into pores. It clung to hair. Then came the feathers. These weren't soft down pillows from a luxury hotel. They were often rough chicken feathers that stuck to the scorching tar, creating a "garment" that was nearly impossible to remove without taking layers of skin with it.

John Malcolm is the name you need to know if you want to understand how bad this got. He was a British customs official in Boston. In 1774, a mob didn't just tar him; they did it in the middle of a freezing January night.

They stripped him to his waist, covered him in hot tar, and then—this is the part people forget—they threatened to cut off his ears if he didn't curse the King. He spent hours in the cold, the tar hardening into a shell. When he finally got home, his skin reportedly came off in strips along with the tar. He actually sent a box of his own peeled skin and feathers to England as a "souvenir" to show the government what the "barbaric" colonists were doing.

It was a PR nightmare.

👉 See also: Why People That Died on Their Birthday Are More Common Than You Think

Why the Mob Chose This Specific Punishment

You might wonder why they didn't just shoot people or hang them. Sometimes they did, but tarring and feathering served a very specific psychological purpose.

It was about dehumanization.

By turning a man into a giant, flightless bird, you stripped away his dignity. You made him a literal laughingstock. In a society where "honor" and "reputation" were everything, being paraded through the streets in feathers was a social death sentence. Even if the person survived the physical trauma, they could never show their face in that town again.

The Sons of Liberty, led by guys like Samuel Adams, were geniuses at this. They didn't always do the dirty work themselves, but they certainly stoked the fire. They used the threat of tarring and feathering in the American Revolution as a way to enforce boycotts.

Basically, if you were a merchant still selling British tea, you’d find a "warning" posted on your door. If you didn't stop, the mob showed up. It worked. Fear is a powerful motivator.

The Social Dynamics of the Crowd

It wasn't just random thugs.

The mobs were often organized. You had "Liberty Poles" erected in the center of town—basically a flagpole that served as a rallying point. If the mob brought you to the pole, you knew you were in trouble.

Sometimes, they’d do a "lite" version called "tawdry and feathering," where they’d put the tar over the victim's clothes instead of their bare skin. It was still humiliating, but it didn't leave the permanent physical scars. It was a warning shot. "Next time," the mob was saying, "the shirt comes off."

✨ Don't miss: Marie Kondo The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up: What Most People Get Wrong

Not Just for Tax Collectors

While we usually associate this with the "Customs Man," the targets were actually pretty diverse.

- Loyalist Printers: If you published a newspaper that took the British side, expect a visit.

- Informers: Anyone suspected of snitching to the British about smuggled goods.

- Apathetic Neighbors: Sometimes, just being "neutral" wasn't enough. You had to be for the cause, or you were against it.

There's a story from 1775 about a man named Thomas Brown in Georgia. He refused to sign a document supporting the Continental Congress. The mob didn't just tar and feather him; they held his bare feet to a fire until he lost several toes.

Brown didn't give up, though. He ended up becoming one of the most ruthless Loyalist commanders of the war, leading a group called the King's Rangers. His backstory is a perfect example of how this kind of violence just bred more violence. It created "vengeance cycles" that tore families apart.

The Myth of the "Peaceful" Revolution

We have this sterilized version of the 1770s in our heads. We think of men in powdered wigs signing documents. But the American Revolution was a civil war.

About 20% of the population remained loyal to the King. Another large chunk just wanted to be left alone to farm their land. The Patriots were often a radical minority who used street violence to force the rest of the population into compliance.

Tarring and feathering in the American Revolution was the ultimate tool for this. It was effective because it was public. It was a performance. When the mob dragged a victim through the streets in a cart, they were sending a message to everyone watching from their windows: "This could be you."

What Most People Get Wrong About the History

People often think this started in America.

Actually, the first recorded instance of tarring and feathering goes all the way back to 1189. King Richard the Lionheart (yes, that one) ordered it as a punishment for thieves in the Navy. It was an old, old tradition of "shaming."

🔗 Read more: Why Transparent Plus Size Models Are Changing How We Actually Shop

The American colonists just perfected the theater of it.

Also, it wasn't a daily occurrence. If you read some history books, you’d think there was a guy in feathers on every street corner. In reality, there are only a few dozen well-documented cases during the entire Revolutionary period. But that’s the point of terrorism—you don’t have to do it to everyone. You just have to do it to a few people in a really public, really gross way, and everyone else falls in line.

The Lingering Stigma

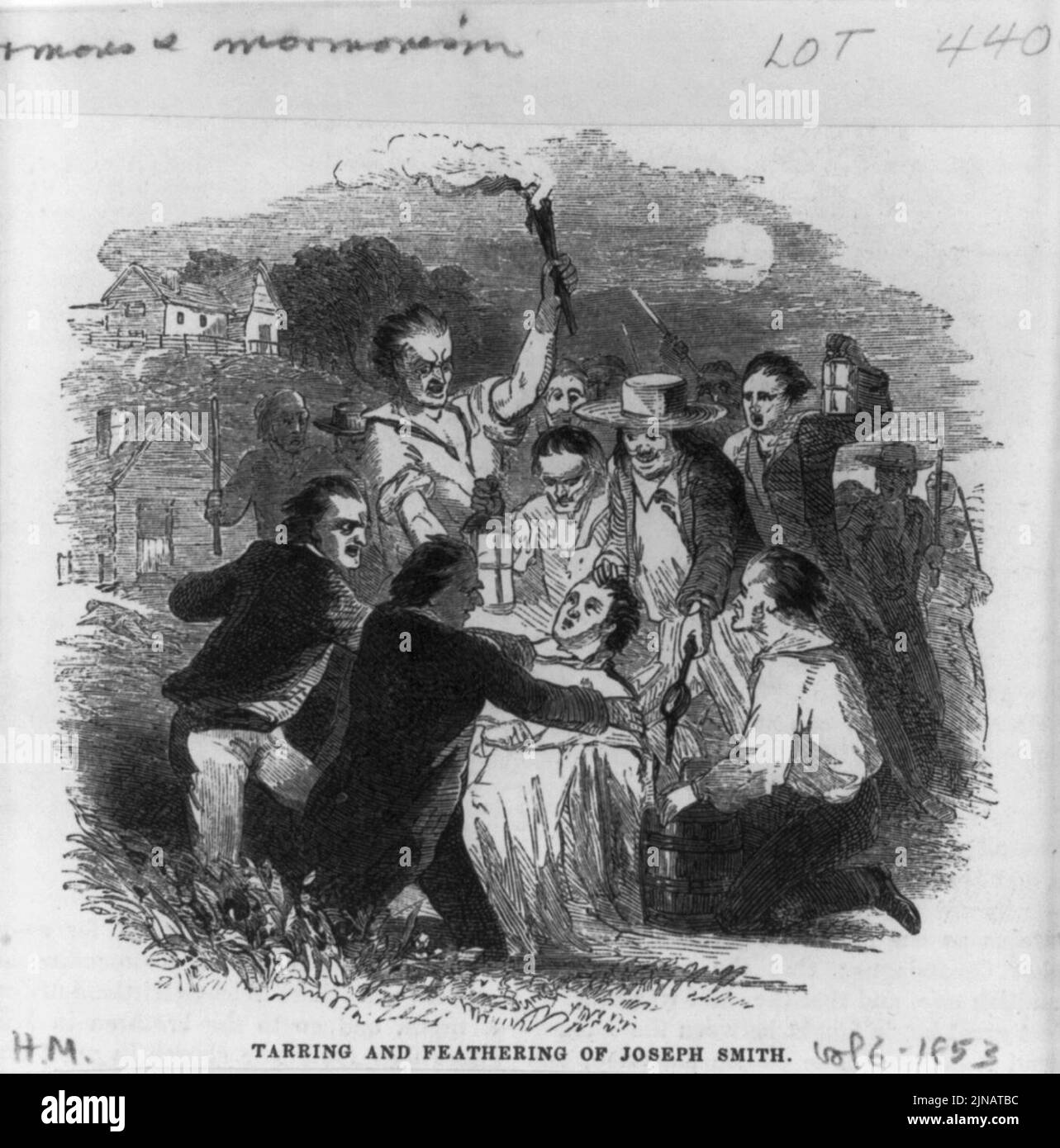

After the war ended, the practice didn't just vanish. It actually stayed in the American "protest" toolkit for a long time. It was used against abolitionists in the mid-1800s, against people of German descent during World War I, and even in some labor disputes in the 20th century.

But it never had the same cultural weight as it did during the 1760s and 70s. Back then, it was the symbol of a brewing rebellion. It was the moment the "rabble" realized they had more power than the guys in the fancy British uniforms.

Understanding the Nuance

It's easy to look back and judge. We like our heroes to be perfect. But the men who fought for American independence were desperate, angry, and often scared. They were taking on the greatest empire on Earth. In their minds, a Loyalist neighbor wasn't just someone with a different opinion; they were a legitimate threat to the survival of the new nation.

Does that justify pouring boiling tar on someone? Honestly, probably not. But history isn't about justification; it's about understanding why things happened. The "Tar and Feather" era shows us the dark side of the "Spirit of '76." It shows us that liberty often has a very high, very messy price tag.

Actionable Steps for History Enthusiasts

If you want to dive deeper into the gritty reality of colonial life and the darker side of the Revolution, don't just stick to the standard textbooks. Here is how to actually find the real stories:

- Read Primary Accounts: Look up the "Journal of the American Revolution." It’s a digital archive that features deep dives into specific incidents like the John Malcolm case.

- Visit the Locations: If you’re ever in Boston, skip the gift shops for a second and go to the sites of the old Liberty Trees. Stand where the mobs stood. It changes your perspective.

- Explore Loyalist Perspectives: To get a balanced view, read The Loyalists: To America's First Civil War by Maya Jasanoff. It explains why some people chose to stay with the King and the hell they went through for it.

- Analyze the Propaganda: Look at the famous 1774 British cartoon The Bostonians Paying the Excise-Man. It depicts the tarring and feathering of John Malcolm. Notice how the British saw the Americans as savages, while the Americans saw themselves as "enforcing" justice.

Understanding the Revolution means looking at the tar and the feathers, not just the ink and the parchment. It was a revolution won in the streets as much as it was in the halls of Congress. Be sure to check the footnotes of your favorite history books; that's where the real, unvarnished stories usually hide.