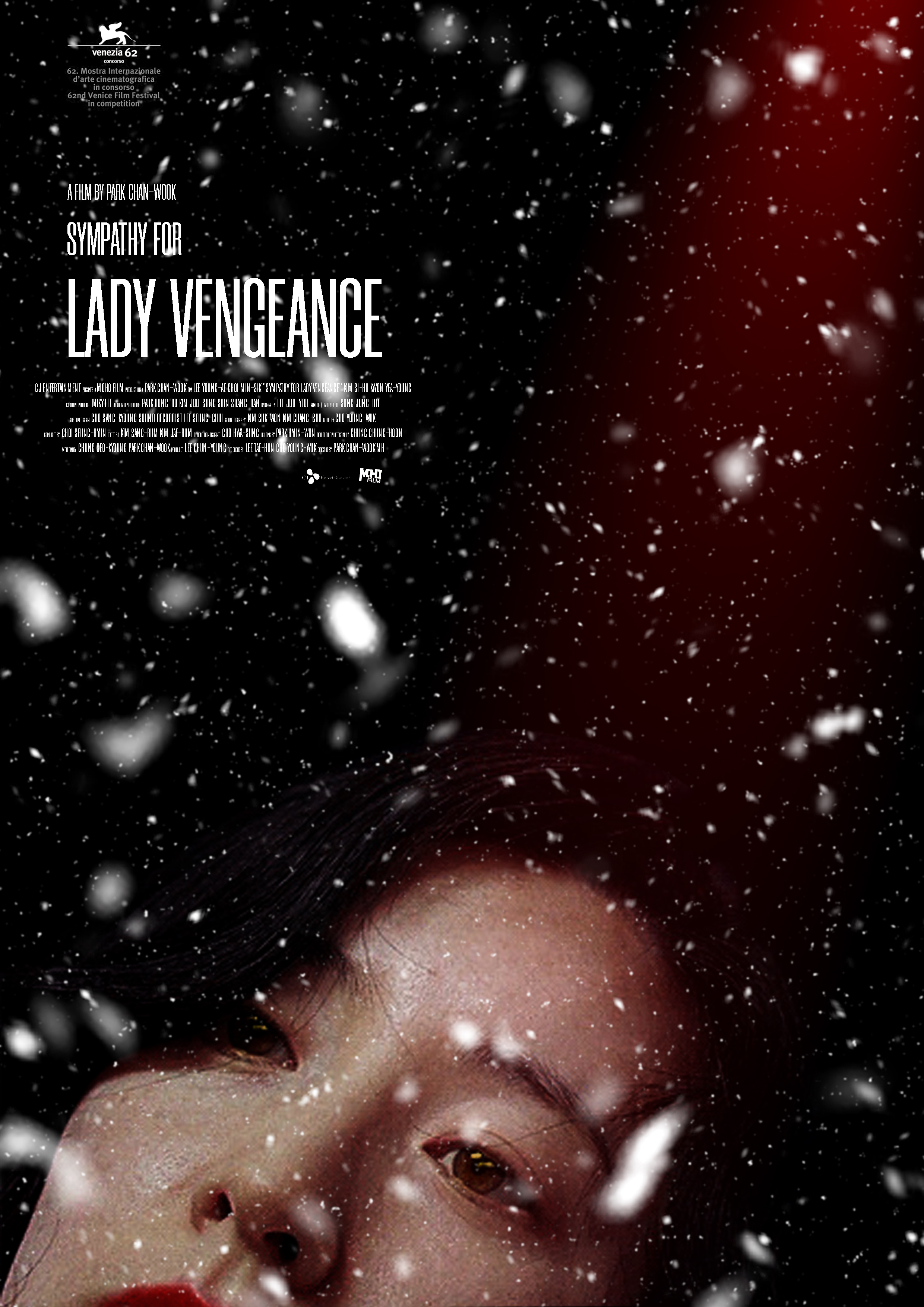

You remember the eyes. That's the first thing anyone notices when they watch Sympathy for Lady Vengeance for the first time. It’s that shock of crimson eyeshadow. It looks like a bruise. It looks like a warning. Honestly, most people who saw Park Chan-wook’s 2005 masterpiece for the first time were expecting a direct sequel to Oldboy, but what they got was something way more internal, way more feminine, and infinitely more messed up.

Lee Geum-ja isn't your typical action hero. Not even close.

When she walks out of prison after thirteen years, she’s met by a priest holding a block of white tofu—a Korean tradition symbolizing a pure life after incarceration. She looks him dead in the eye, flips the tray, and tells him to "go screw himself." It’s one of the most iconic "I’m back" moments in cinema history because it rejects the very idea of forced redemption. She doesn't want to be pure. She wants to be even.

The Vengeance Trilogy's Most Complicated Child

We talk about the "Vengeance Trilogy" like it’s a unified set of rules. It isn't. Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance was about the crushing weight of class and bad luck. Oldboy was a Shakespearean tragedy wrapped in a hammer fight. But Sympathy for Lady Vengeance is different because it focuses on the communal nature of trauma. It’s not just one person’s vendetta; it’s a shared burden among victims.

Director Park Chan-wook basically spent the early 2000s dissecting how revenge rots the soul. If you look at the film's original Korean title, Chinjeolhan Geum-ja-ssi, it translates to "Kind-hearted Ms. Geum-ja." The irony is so thick you can't even cut it with a knife. She spent thirteen years being the "perfect" prisoner—the "angel" who helped everyone—just so she could recruit an army of debtors once she got out. It’s tactical. It’s cold.

It’s also surprisingly funny in a pitch-black way.

Take the scene where she's designing her custom pistol. It’s a work of art. It’s silver, ornate, and looks more like jewelry than a weapon. This reflects the film's entire aesthetic. While the previous films were gritty and sweaty, this one is baroque. It’s beautiful to look at, which makes the underlying violence feel even more stomach-turning. You’re lured in by the red heels and the snowy landscapes, then hit with the reality of what a child killer actually looks like.

Why Mr. Baek is the Ultimate Villain

Choi Min-sik, the guy who played the protagonist in Oldboy, shows up here as the villain, Mr. Baek. It’s a brilliant bit of meta-casting. In Oldboy, we rooted for him. Here, he’s a spineless, pathetic monster who kidnaps and kills children for no grand reason other than he’s bored and wants money.

📖 Related: Al Pacino Angels in America: Why His Roy Cohn Still Terrifies Us

The movie handles the reveal of his crimes with a specific kind of dread. We don't see the acts; we see the aftermath. We see the belongings of the children. This is where the film shifts from a solo mission into something else entirely. Geum-ja realizes that her own personal grudge—being framed for a murder she didn't commit—is small compared to the collective grief of the parents whose children never came home.

The Logic of the Group Execution

The third act of Sympathy for Lady Vengeance is where most viewers get uncomfortable. It’s the scene in the abandoned schoolhouse. Geum-ja gathers the parents of Baek's victims. She gives them a choice. They can go to the police, or they can take turns with him in the back room.

Think about that for a second.

Most revenge movies end with a big shootout or a heroic one-on-one duel. This movie ends with a bunch of middle-aged parents putting on plastic ponchos so they don't get blood on their clothes. It’s pathetic. It’s messy. It’s incredibly sad. There is no glory in it. The sound of the knife hitting bone while the other parents sit in the classroom waiting their turn is one of the most haunting sequences in modern film history.

Kim Young-hwa, a prominent Korean film critic, once noted that Park Chan-wook wasn't trying to justify revenge here. He was showing the "banality of vengeance." By the time the parents are finished, they don't look relieved. They look exhausted. They look like they've lost even more of themselves.

Cinematic Style and the "Fade to Black and White"

If you really want to understand the soul of this movie, you have to find the "Fade to Black and White" version.

Park Chan-wook originally wanted the film to slowly lose color as it progressed. As Geum-ja gets closer to her goal, the vibrant reds and golds drain away until the final scenes are in stark monochrome. This wasn't just a gimmick. It was a visual representation of her soul dying. By the time she’s standing in the snow at the end, the world is gray. The "pure" white tofu she finally tries to eat is just as colorless as her life has become.

👉 See also: Adam Scott in Step Brothers: Why Derek is Still the Funniest Part of the Movie

He used a specific process in post-production to ensure the blacks were deep and the highlights stayed crisp. If you’ve only seen the standard theatrical cut, you’re missing half the psychological weight. The color version feels like a fairy tale. The black-and-white version feels like a funeral.

The Daughter Connection

The emotional core isn't the killing; it's Jenny.

Geum-ja’s daughter, who was adopted by an Australian family, is the only reason Geum-ja has any humanity left. The scenes in Australia are shot with a weird, dreamlike quality. They’re awkward. Jenny doesn't speak Korean; Geum-ja barely speaks English. They communicate through a weird mix of sign language and raw emotion.

This relationship is what separates Sympathy for Lady Vengeance from a standard "kill-list" movie. Geum-ja is terrified that her daughter will grow up to be like her. There’s a scene where Jenny asks why Geum-ja’s eyes are so red, and Geum-ja tells her it’s so she doesn't look kind. She’s trying to protect her daughter from the "angel" persona she used to survive.

Addressing the Misconceptions

People often call this a "feminist revenge flick." That’s a bit of a simplification.

While it’s true that Geum-ja is a powerhouse female lead, the movie is more interested in the failure of the feminine archetype of the "nurturer." Geum-ja is a mother who failed her child. She’s a "sister" in prison who used her kindness as a weapon. She’s not a hero. She’s a victim who became a victimizer to find a sense of peace that never actually arrives.

Another common mistake? Thinking this movie is about justice.

✨ Don't miss: Actor Most Academy Awards: The Record Nobody Is Breaking Anytime Soon

Justice is what happens in a courtroom. Vengeance is what happens in a basement. The film goes out of its way to show that the legal system failed everyone involved. The detective who originally arrested Geum-ja knows she’s innocent, but he helps her with the revenge anyway because he feels guilty. It’s a cycle of systemic failure.

Lessons from Geum-ja’s Long Game

If we’re looking for "actionable" takeaways from a movie this dark, it’s not about how to build a gun or how to hide a body. It’s about the psychology of the long game and the reality of closure.

- Patience is a weapon. Geum-ja waited thirteen years. She didn't rush. She built a network. In the real world, this is about the power of social capital. She helped people when they were at their lowest, and they repaid her when she needed it most.

- Revenge is a debt that never clears. The ending of the film is one of the most somber ever captured. Geum-ja tries to wash her face, but the red won't come off metaphorically. The lesson here is that "closure" is a myth sold by talk shows. You don't close a wound by cutting someone else; you just get more blood everywhere.

- The "Why" matters more than the "How." Geum-ja’s plan was flawless, but her heart wasn't in it by the end. If you’re pursuing a goal out of spite, you’ll find that the victory tastes like ash.

Where to Go From Here

If you’ve already seen the film, you need to watch the director’s commentary. Park Chan-wook is incredibly candid about the transition from the male-dominated violence of Oldboy to the "elegant" violence here.

Look for the 20th Anniversary restorations that have been making the rounds in boutique Blu-ray circles (like Arrow Video or Criterion). The 4K transfers do justice to the cinematography by Chung Chung-hoon, who later went on to shoot Last Night in Soho and It. You can see the evolution of his style—how he uses shadows to frame Geum-ja not as a person, but as a ghost haunting her own life.

If you’re a fan of the genre, compare this to the 2023 film The Glory (the Netflix series). You can see Geum-ja’s DNA all over it. The "kind" protagonist who uses a smile to mask a decade-long plan of absolute destruction is a trope that Sympathy for Lady Vengeance perfected.

Finally, sit with the ending. Don't look for a happy resolution. Watch the way the snow falls. It’s a quiet, devastating reminder that some things can't be fixed, only endured. Geum-ja’s journey isn't a roadmap; it's a cautionary tale about what happens when you let your past dictate your entire future.

Go watch the "Fade to Black and White" cut. Pay attention to the music—the Vivaldi-inspired score by Choi Seung-hyun. It turns a sordid tale of murder into a requiem. It’s a hard watch, but it’s an essential one for anyone who wants to see what happens when the "angel" finally decides she’s had enough.

The most important thing to remember is that the "sympathy" in the title isn't for the victim. It's for the woman who has to live with what she's done. That’s the real tragedy. It’s not that she failed to get revenge; it’s that she succeeded.

Practical Next Steps:

- Seek out the specific "Fade to Black and White" version on physical media or high-end streaming platforms like MUBI; the transition provides a completely different psychological experience.

- Watch the entire Vengeance Trilogy in order (Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance, Oldboy, Sympathy for Lady Vengeance) to see how Park Chan-wook’s philosophy on violence evolves from external chaos to internal decay.

- Read the production notes regarding the "red eyeshadow." It was specifically chosen to look like a "bloodstain that wouldn't wash off," serving as a constant visual cue for the character's inability to find peace.

- Analyze the dinner scene at the end as a subversion of the "Last Supper," where the characters are bonded by sin rather than salvation.